International Crime Film/Film Noir: 1923-1963

Introduction

Contrary to the opinion of Sura Wood, quoted on the page About the Film Noir File Website, and that of many other writers, film noir is absolutely not “a uniquely American phenomenon.” Instead, as I explain below, American film noir needs to be placed in historical context of a 40-year international current of crime fiction and crime film. And, to a crucial extent, the cultural context for these crime stories is the expansion of realism in different kinds of arts before WWII, both inside and outside of the US.

Finally, as I document in my tables associated with UK and US spy noirs, film noir’s origins in Britain and America aren’t in crime films but in spy films. Why? Because of the historical context of, first, the impending, and then next, the occurring Second World War. See the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.

In January-February 2014, Noir City 12 at the Castro Theater in San Francisco presented a series of film noirs from around the world, in a program entitled, “It’s a Bitter Little World.” Here is the trailer. (I discuss this series in the Addendum to the page The Old Guard Changes.)

For an excellent festival of international film noir, see the schedule at San Francisco’s Roxie Theater, 2015, for “A Rare Noir Is Good to Find! International Film Noir, 1949-1974.” Below is one of the publicity postcards, followed by the promotional YouTube video.

For the sequel, see the schedule at San Francisco’s Roxie Theater, 2016, for A Rare Noir Is Good to Find! International Noir Revisited, 1947-1966. The promotional video is embedded in the Roxie schedule.

In January-February 2020, Noir City 18 at the Castro Theater in San Francisco presented another series of film noirs from around the world, “Noir City: International II.” Unlike “International I” in 2014, in which many but not all of the 27 films screened were foreign, in this year’s series every one of the 24 films in the program is foreign.

Presentation

This period begins with the cataclysm of World War I and ends during the high tide of the post-WWII economic “boom” in the early 1960s. It is the Great War that triggers, internationally, realism (and, often also, cynicism and darkness) in a variety of art movements, which include theater and painting as well as literature and cinema.

For example, after WWI, not only “higher” literature became more streamlined (more real), but also crime fiction. It’s not important who was first to write in a direct, non-Victorian, style: Ernest Hemingway, John Carroll Daly or Dashiell Hammett. They all did so around the same time because they were part of a larger international cultural shift. By the late 1920s-early 1930s, spy fiction in Britain had markedly been changed by W. Somerst Maugham, Eric Ambler and Graham Green. They had been influenced by American hardboiled short stories and novels, and they wanted to make their spy novels similarly “realistic.” Also in these years, Georges Simenon’s first Inspector Maigret books were published, which introduced a new “psychological realism” to crime fiction.

The 40-year international current of crime films begins with the German Strassenfilm (Weimar street film) and is followed by, for example, French poetic realism, American film noir, crime films in Italian neo-realism, Mexican cabareteras of the late 1940s to mid-1950s, Spanish cine negro of the 1950s, and in both Britain and France film noirs from the 1940s through new waves in those countries in the early 1960s.

All of the kinds of films in this current were associated with realism. And the audiences and critics understood (and approved or disdained) that this realism meant the films showed lives of the working class and had progressive if not left-wing politics — these crime films were seen as critiquing the social order of their countries. Similarly, the working class is part and parcel of the fictional characters as well as reading audiences of the burgeoning international paperback industry’s output of spy novels, Maigret, hardboiled pulps, etc.

Below I’ve quoted descriptions of many different kinds of cinema that were made in Germany, France, Italy, Britain, Spain, Mexico, Argentina, India, Japan, and South Korea from the 1920s to the 1960s. Realism was one of the most important aspects that was internationally shared in these films. Crime stories for plots, and expressionism/dark imagery for a visual style were also commonly found.

The challenge to orthodoxy about American film noir is to recognize that, because of an international historical context, “film noir” was an international cinema. The films may have been more numerous in some countries than others. The films may have been made in somewhat different years. Nonetheless, taken in a long perspective, the international overlap in film noir was striking compressed in time across the globe.

In the Addendum below, I have cited books that challenge the common tenet of the hardboiled paradigm that film noir is an American phenomenon.

Germany

German Expressionism

“[Expressionism] lasted roughly between 1906 and 1924…[It] created an embracing mood and texture, dependent on a distinct visual style that used high contrast, chiaroscuro lighting where shafts of intense light contrast starkly with deep, black shadows, and where space is fractured into an assortment of unstable lines and surfaces, often fragmented or twisted into odd angles. Overall, Expressionist cinema used a highly designed and carefully composed mise-en-scene that was anti-naturalistic. Expressionist cinema cultivated displaced, decentered narratives, nested in frame tales, split or doubled stories, voiceovers and flashback narration. Both Expressionism’s style and its narrative patterns influenced film noir.” (Andrew Spicer, Film Noir, Pearson Education Limited, 2002, 11-12)

German Strassenfilm (Street Film) and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity, New Sobriety)

“By the late 1920s and early 1930s German films showed signs of change toward an increasingly realistic style. Unsavory, shadowy, and downbeat “street pictures,” known as Kammerspielfilm, such as G. W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street (1925) and Pandora’s Box (1929), combined stark realism with expressionist style – and aesthetic melding that influenced film noir.” (Sheri Chinen Biesen, Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, 16)

“German Expressionism is always cited as the major influence on film noir’s arresting visual style and also its pessimistic mood. However, it was the influence of Weimar cinema (1919-1933) as a whole, rather than just ‘Expressionism’, that was profound, and also more complex, multifaceted and indirect than is often supposed…Without denying the importance of Expressionism, [it should be] emphasized the significance of the Strassenfilm, the ‘street film,’ as an influence on film noir. The street film was part of what is usually known as Neue Sachlichkeit or ‘New Objectivity’ which departed from the Gothic scenarios of Expressionism to concentrate on the social realities of contemporary German life. The subject matter of this cycle of films, beginning with Karl Grune’s Die Strasse (The Street, 1923), was the descent of a respectable middle-class protagonist into the ‘overcharged landscape’ – fascinating, thrilling, but dangerous – of city streets at night. In these films one can perceive a proto-noir urban milieu consisting of deep shadows, rushing traffic, flashing lights and cast of underworld characters: black marketers, gamblers and con men and, above all, the femme fatale who embodies the temptation and threat of illicit desire.” (Andrew Spicer, Film Noir, Pearson Education Limited, 2002, 11, 22)

“[P]erhaps too great an emphasis on the passionate distortions of Expressionism (from Munch’s ‘The Cry’ onwards) at the one end of the scale and the chic decadence of Cabaret and the like at the other has allowed [people] to overlook what came between. Our quest now will be concerned rather with a particular constructive vision originating at the end of the First World War, a new realism that sought methods of dealing both with real subjects and with real human needs, a sharply critical view of existing society and individuals, and a determination to master new media and discover new collective approaches to the communication of artistic concepts. The constructive vision in question will be found applied in various fields – first in ‘pure’ are in tow or three dimensions, then in photography, the cinema, architecture, various forms of design and the theatre – often according to principles derived, far more sophisticatedly than before 1914, from the rapidly developing technological sphere: that is, not from the outward appearance of machines so much as from the kind of thinking that underlies their design and operation. The critical vision comes out of Dada and the disillusionments of the war and the German Revolution; it is in effect a cooler and more skeptical counterpart to the optimistic humanitarianism of the Expressionists in the years 1916-1919, and as this began deflating it moved into the gap, to become known under the slightly misleading title of The New Objectivity.” (John Willet, Art and Politics in the Weimar Period: The New Sobriety 1917-1933, Pantheon Books, 1978, 11)

“The period after 1924 produced a return to social normalcy in Germany. As a consequence the German cinema began to turn away from the abnormal and artificial psychological themes of Expressionism and Kammerspiel and towards the kind of literal (but still studio-produced) realism exemplified by Strassenfilme of the second half of the decade – G. W. Pabst’s Die freundlose Gasse (The Joyless Street, 1925), Joe May’s Asphalt (1929), and Piel Jutzi’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1930). Named for their prototype, Karl Grune’s Der Strasse (The Street, 1923), these films all dealt realistically with the living conditions of ordinary people in the post-war period of inflation and confirmed the spirit of Neue Sachlichkeit which entered German society and art at every level during this time. Lack of expectation, pessimism, resignation, disillusionment, and a desire to accept ‘life as it is’ were the major characteristic of Neue Sachlichkeit, and these reconstructed in the form of merciless social realism in the street films. The master of the new realism was accepted to be the Austrian-born director G. W. Pabst (1886-1967). Trained in the theater, Pabst was a latecomer to the Weimar cinema who directed his first film, Der Schatz (The Treasure) in 1924. His next film, however, was Die freudlose Gasse (The Joyless Street, 1925), which achieved world recognition as a masterpiece of cinematic social realism. In some countries recognition came in the form of censorship; England banned Die freudlose Gasse. The film concerns the financial and spiritual destruction of the middle classes through inflation in post-war Vienna, focusing upon the lives of several impoverished bourgeois families striving to uphold their self-respect and propriety under the conditions of a secret starvation. The misery of their existence is contrasted with the excessive pleasure-seeking life style of the war profiteers. Daughters of the middle class, played by the Swedish actresses Asta Nielsen and Greta Garbo, sell themselves into prostitution to save their families, while the wealthy amuse themselves at luxurious black market nightclubs, where these girls must eventually come to be bought. Pabst took ‘life as it is’ with a kind of photographic realism, without any reference to sentimentality or symbolism.” (Secil Deren, Cinema and Film Industry in Weimar Republic, 16-17)

Rubble Films (Trümmerfilm)

Martina Moeller, in her Rubble, Ruins and Romanticism: Visual Style, Narration and Identity in German Post-War Cinema (Transcript-Verlag, 1913), in the topic, “Rubble Films: Common Features and Main Differences,” says, “Rubble films do not have a unifying set of narratives or visual features.” She goes on to “distinguish among three main categories. First, more or less commercial entertainment films that were mainly produced in the Western zones…All of these films largely depend on patterns of classical film style and have as their goal to reconcile the audience with and divert them from past and present trouble. Critical insight about past and present problems is mainly ignored, and the post-war reality of rubble and ruins appear only as a decorative element in these cheerful, funny, or dramatic films. The second category includes films produced in the eastern and western occupation zones that employ filmic realism in order to reflect the past and present events in a serious manner…The last category consists of films that also rely on a realist style that is often shaped by formalist tendencies in combination with a stylish and narrative Romantic discourse of decline, fragmentation, and crisis. The Romantic patterns in these films function as a device to question past and present events. Often artistically challenging, these films demand serious introspection from the audience due to their lack of patterns typical of the classical style and their lack of cheerful entertainment value. Stylistically, these films revert more completely than many other rubble films back to formalist tendencies previously seen in Weimar cinema and its successor, film noir. The most important films in this category are The Murderers Are Among Us (1946) and Second Hand Destiny (1949), Man of Straw (Der Untertan, 1951) by Wolfgang Staudte, The Blum Affair (Affaire Blum, 1948) by Erich Engel, The Last Illusion (1949) by Josef von Baky and Fritz Kortner, The Lost (1951) by Peter Lorre, and to a certain extent Film Without a Name by Rudolf Jugert and Epilogue (Epilog, 1951) by Helmut Käutner, as well as Street Acquaintance by [Peter] Pewas [1948]. (111, 113)

France

Poetic Realism

Longstanding differences of opinion in discussions about French film noir are whether it exists in the 1930s and, if so, whether the films must therefore be those that are also considered poetic realist films. (I provide detailed explanations of poetic realism below.)

For example, Robin Buss, in one of the earliest books about subject sees French film noir as having nothing to do with the 1930s. In French Film Noir (Marion Boyars Publishers, 1994, 2001), Buss skips the 1930s and poetic realism. In his filmography of 101 French film noirs, the earliest is L’Assassin Habite au 21 (The Murderer Lives at Number 21), which was released in 1942.

In contrast, in the anthology edited by Andrew Spicer, European Film Noir (Manchester University Press, 2007), Ginette Vincendeau understands French film noir to exist in the 1930s, but only in poetic realist films. In her essay, “French film noir,” under the subsection, “The 1930s: the building blocks of French film noir” (24-28), Vincendeau explains the relevance of poetic realism to film noir.

“[T]he dominant ‘dark’ style of the period [was] poetic realism. This term designates a pervasive style of dark urban dramas with pessimistic narratives infused with fatalism, usually set in working-class or underworld Paris. Poetic realist films elicit a sense of beauty and tragedy through visual style, elevating humble characters and everyday surroundings to the level of ‘poetry’…Stylistically, Poetic-realist films are undoubtedly ‘noir’. The gloom of the city streets and canal banks is illuminated by shiny cobblestones and pierced by mist-shrouded lampposts and gleaming nightclub signs.” (26)

The key points here are that Vincendeau locates French film noir in the 1930s (instead of later) and that she associates it with poetic realism. That is, there isn’t French film noir in this decade apart from poetic realism.

Below are more descriptions of poetic realism.

“Like many realist movements, French poetic realism was linked to certain historical moments as socialist governments and outlooks replaced conservative regimes. French poetic realism developed in the 1930s as the expression of a specifically French aesthetic and moral sensibility linked to a nineteenth-century literature which was encouraged by a changing political climate, and the collapse of commercial studio conglomerates which had dominated the French film industry. The rise of poetic realism is related to the rise and fall of the Popular Front, a consolidation of left-wing parties and factions which came to power in 1936. For many, the Popular Front represented the possibility of far-reaching social reforms. But owing to an adverse economic climate and the looming possibility of war with Germany, the Popular Front achieved little. While key poetic realist films revolve around working men and women, they are pessimistic in mood an often end tragically. Unusually for realist cinema, poetic realism was studio-based, its portraits of ordinary experience generated from the conventions of screenwriting and camerawork, sets, lighting and actors available to small independent producers. Real locations and non-professional actors figure little in the evolution of the style. Streets and rooms in Paris were meticulously rebuilt in the studio. As the name suggests, poetic realism attempted to combine the realistic with the lyrical or emotional, showing how the poetic could arise out of the situations and dimensions of everyday life. In a cheap room a murderer waits to die in Le Jour se leve, his redemption his love for a woman. Le Crime d M Lange tells of a publishing company which flourishes as a workers cooperative following the shooting of the grasping publisher. In Hotel du Nord, two lovers pledge to commit suicide together. The generation of poetic or lyrical elements out of the grubby facts of life anticipated realist movements from Italian neo-realism to the British New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s.” (Richard Armstrong, Understanding Realism, British Film Institute, 2008, 69-70)

“Poetic Realism drew on an indigenous tradition of crime fiction that concentrated on the everyday, the ordinary and the banal…Poetic Realism’s visual style was indebted to Weimar cinema. However, Poetic Realism was a distinctive modification of Expressionism, exhibiting a softer and less extreme use of chiaroscuro. Poetic Realism is concerned to create a distinctive milieu with shiny cobblestones and neon-lit nightclubs that are site of danger and desire, and much atmospheric use is made of shadow or fog. But the city was rendered less abstractly than in the Weimar ‘street film.’ The pace of Poetic Realism is closer to Weimar than to Hollywood, using tightly controlled camera movements and long takes, reframing rather than cutting within their deep focus settings.” As Dudley Andrew observes [in Mists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French Film, Princeton University Press, 1995], the pace and insistent mise-en-scene makes Poetic Realism a cinema of character rather than events, and its typical protagonists anticipate film noir. The dangers of desire, as in the ‘street film,’ were represented by the femme fatale, or ‘lost girl,’ in her beret and shiny raincoat that transferred the reflections of the night-time city onto her body as if she were all surface, without substance. The male protagonists tend to be confused, passive, divided and deeply introspective. The dominant actor was Jean Gabin, always marked as an outsider, romantic, but possessed by self-destructive forces. Such was Gabin’s stature that he created a new kind of male hero, a modern Everyman who is complex and ambivalent, both sexually and socially. His tough masculine power is often outweighed by a ‘feminine’ sensitivity and vulnerability, a clear difference from his American counterparts, and his social status is ambiguous or confused. He often plays a decent workman or soldier who, through circumstances beyond his control, is criminalized. Like many noir heroes, his past is constantly alluded to, but never fully revealed. Unlike his American successors, Gabin always dies, making these French films generally bleaker and more heavily fatalistic that film noir. The lighting, milieu, iconography and characterization, especially Gabin’s angst-ridden hero, all prefigure noir.” (Andrew Spicer, Film Noir, Pearson Education Limited, 2002, 15-16)

Note that Andrew Spicer’s perspective above differs from Vincendeau’s. Whereas she believes there are French film noirs in the 1930s, albeit they are poetic realist films, Spicer only sees poetic realist films as prefiguring French film noir, which thus only comes into its own after the 1930s.

Eight years later, within Spicer’s Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2010), his view about French film noir and poetic realism seems contradictory. In the Introduction, under the topic “THE ORIGINS OF FILM NOIR,” Spicer says, “Because poetic realism was not only successful in France but also widely admired internationally, including in America, and because several Austro-German émigrés worked in Paris before going on to Hollywood, it acted as a bridge, culturally and historically, between expressionism and film noir” (xlii). Similarly, in the entry for “POETIC REALISM,” Spicer says, “Aesthetically, poetic realism was the ‘bridge’ between [German] expressionism and [French] film noir….” (235) Furthermore, since Spicer also claims that poetic realism prefigures French film noir, the bridge metaphor must also represent a passage in time from earlier poetic realism to later film noir. However, what Spicer says in the entry for “FRENCH FILM NOIR” doesn’t seem to conform to his notion that poetic realism is a bridge to film noir and that it precedes film noir.

“French film noir has its roots in the broad corpus of French crime fiction that extends back to the mid-19th. century. The most important author was Georges Simenon, whose dark, morally ambiguous stories, set in drab everyday surroundings, deal with characters whose lives are wrecked by crime. The three Simenon adaptations released in 1932 – Jean Renoir’s La Nuit du carrefour (Night at the Crossroads), Julien Duvivier’s La tête d’un homme (A Man’s Neck), and Jean Tarride’s Le Chien jaune (The Yellow Dog) – constitute the beginning of French film noir, though preceded by Renoir’s La Chienne (The Bitch) in 1931. French film noir’s key characteristic is a concentration on atmosphere, character, and place rather than action, as exemplified in prewar poetic realism, whose films, including Le Quai des Brumes (Port of Shadows, 1938) and Le Jour Se Lève (Daybreak, 1939), were often more pessimistic and fatalistic than film noir. French film noir is thus darker than its American counterpart with a greater moral ambiguity, as exemplified by Jean Gabin’s doomed gangster in Pépé le Moko (1937).” (97)

Let me indicate three ways Spicer contradicts his other references to French film noir and poetic realism, which I provide above. First, the films that Spicer says “constitute the beginning of film noir” actually precede the films of poetic realism, albeit by only a few years. Second, he says that “French film noir’s key characteristic is…exemplified in prewar poetic realism.” Third, he says, “French film noir is thus darker that its American counterpart…as exemplified by…Pépé le Moko. In other words, here Spicer isn’t drawing a distinction between poetic realism and French film noir. Instead, he is suggesting – and I think correctly – that there are French film noirs in the (early) 1930s that aren’t poetic realist films and also there are poetic realist films (later on) that are also appropriately considered French film noirs. This interpretation is reinforced by Spicer’s filmography of French film noirs (452-456), whose earliest entries are the titles cited in the paragraph above.

In addition to Spicer’s Historical Dictionary of Film Noir, there are two other large filmographies with numerous film noirs from many countries, and they treat the question of French film noirs in the 1930s differently. John Grant’s A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir (Limelight Editions, 2013) includes French film noirs from the 1930s (whether they are also considered poetic realist films or not). On the other hand, in Spencer Selby’s The Worldwide Film Noir Tradition (Sink Press, 2013), of his 177 French film noirs, the earliest is Le Dernier des six (The Last One of the Six), which was released in 1941.

French Film Noir

In pathbreaking work, which will be made publicly available in a forthcoming book, Don Malcolm has recast the history of French film noir in several ways: 1) by contending that film noir itself begins in France; 2) by identifying a large number of film noirs in the 1930s, many of which aren’t considered poetic realist films; 3) by identifying a huge number of film noirs for his time period (1931-1966); and 4) by exposing how the existence of these films was “lost” (suppressed) with coming of the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague).

What follows are quotations from various materials that Malcolm has made available to the attendees of The French Had a Name for It, four French film noir festivals he has hosted at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco.

Below are excerpts from an interview with Malcolm, which was printed in a brochure for The French Had a Name for It 4.

Q: How many French film noirs are there, anyway?

A: Over 400 from 1931-1966.

Q: Why don’t people know more about these films?

A: They were kicked to the curb in the early 60s by the advent of the Nouvelle Vague.

Q: Why?

A: A successful but misguided effort to change the nature of film…we lost at least as much as we gained.

[In the 2018 French Film Noir calendar that was sold at the 2017 festival, Malcolm elaborates on these points: “Even die-hard cinephiles still believe that French film noir is focused around a handful of compelling titles that film historians refer to as ‘Poetic Realism,’ and a series of gangster films in the 1950s taking their cue from American film noir classics. Don’t believe them as it is only about 5% of the story…We are missing two incredibly important points thanks to the success of the filmmakers associated with the Nouvelle Vague and Cahiers du Cinema: first, that film noir as we know it now was actually invented in France in the 1930s; second, that the success of the Nouvelle Vague insurgency was such that 95% of the films made in France in the years between 1931 and 1966 were kicked to the curb, hidden in plain sight, and left for dead – they were dismissed as inadequate to the demands of an ‘outsider cinema.'”]

Q: What kind of film noir were they making in the 1930s?

A: Three strains emerged in France: the hardboiled detective film, the poetic realist film, and the exotic espionage film.

Below is an excerpt from an interview with Malcolm, which was printed the program for The French Had a Name for It 3.

“The current ‘French film noir canon,’ as understood and accepted by virtually scholars and fellow travelers, is about three dozen films, roughly half of which are ‘heist’ films.

“Those are all good films, some are great, but most of them are really too involved in aping some aspect of American film noir and tend to misrepresent France’s indigenous response to the philosophical underpinnings of a subversive, despairing aesthetic. The heist films get in the way of a much broader understanding of how French noir developed from three interrelated strains in the 30s, underwent a unique ‘baptism of fire’ during the Occupation years, was galvanized into a kind of Golden Age of proletarian existentialism through its reception of the first American noirs, and then continued all the way into the mid-60s unimpeded by the type of Blacklist situation that took the wind out of the sails of American noir in the early 50s.

“As a consequence, French noir in its latter stages is just as diverse in setting, characters, and source material as was the case for American noir in the 1940s.”

Below is an excerpt from the text in Malcolm’s program for The French Had a Name for It 2.

“It is a tale unique in film history: while the French coined the term film noir in the years immediately following World War II and championed it as a fascinating American export, the Nouvelle Vague – nurtured in a critical climate free from the fear-mongering that plagued America – mounted a furious attack in the pages of Cahiers du Cinema on most of the films produced in France in the 1940s and 1950s. French film noir was collateral damage.

“As a result, nearly 90% of the indigenous film noirs of France found themselves cast into a cultural purgatory from which most of them have still not escaped.”

Below are links to the Roxie Theater programs for the four festivals Don Malcolm has presented.

2014: The French Had a Name for It: Classic French Noir from the 40s through the 60s

2015: The French Had a Name for It 2: Lovers & Other Strangers

2016: The French Had a Name for It 3: Further Explorations in Classic French Noir, 1939-65

2017: The French Had a Name for It 4: Despair • Delerium • Destiny — French Film Noir 1935-1966

French New Wave

The promotion and celebration of the French New Wave, by its filmmakers and cinema critics, at the expense of – at the conscious erasure of the historical memory of – French film noir has been cogently argued by Don Malcolm in his publicity materials (“swag”) that have been available at his programs at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco. For excerpts from those materials, see the entry above for French Film Noir.

“The year 1959 was something of a watershed in world cinema and saw the emergence of new waves across Europe. None is more renowned than the French New Wave…New Wave film-makers were reacting against what they saw as an outmoded cinema encrusted with the scenarios, conventions and stars of the 1930s and 1940s. They took their cameras on to the streets and into the cafes, apartments and lives of young Parisians. They employed non-actors and those just starting out. They captured French youth at a particular moment. They chopped stories up or made them plotless like experience. They used jump cuts and ellipses that broke with industry convention and drew attention to the fact that fictional film is also a record of the reality of the film’s making. They use ‘low’ sources such as French and American pulp novelettes and films, as opposed the ‘high’ literary sources favored during the classical period. They established a new pantheon of stars. No matter whether set in the present – Breathless – or in the past – Jules and Jim – New Wave films always seemed to be set in the here and now.” (Richard Armstrong, Understanding Realism, British Film Institute, 2008, 77, 78)

Italy

Italian Neo-Realism

“The most famous realist movement in film history, Italian neo-realism was the first major European alternative to the Hollywood realist aesthetic to appear after World War II. Not simply a new way of making films, new-realism had a moral and political dimension. Emerging out of Italy’s experience of fascist dictatorship, war, military occupation and economic hardship, neo-realism directors sought to turn all this into a new kind of unadulterated aesthetic, one that showed the world as it really is…The best neo-realism displays a regard for and a responsibility toward real experience such that watching it you feel as though you have seen a film that was actually about something. With their dramatic music and histrionic acting, works such as Ossessione, Rome, Open City, and Bicycle Thieves may seem melodramatic to us today; however, the shift from the middle-class preoccupations of prewar Italian cinema (as shown in films sponsored by the fascist regime such as the polished middle-class melodramas which came to be known contemptuously as ‘white telephone movies’ because of the plush white telephones found in every penthouse and hotel suite) to the locations and protagonists of a ravaged postwar Italy imparted a genuine sense of immediacy to postwar critics and audiences. These films constituted an influential attempt to find solutions to issues of representation that would be tackled differently in different countries in subsequent decades. Neo-realism’s unscripted style and bustling scenes shot in black-and-white and live with the interactions to close-knit urban communities still seem to epitomize what we mean when we talk of realism.” (Richard Armstrong, Understanding Realism, British Film Institute, 2008, 71, 74-75)

“Italian neo-realism was the product of the Second World War and the defeat of Italian and German fascism. Ideologically it arose from the need, widely felt throughout Italy and most clearly articulated among intellectuals of the left, to break with the cultural heritage of fascism and in particular with rhetorical artistic schemata which seemed to bear no relation to life as it was lived….This was also a period of political and social ferment, in which a public could be found for an art which sought to reflect immediate reality in simple terms….Authentically the ‘realism’ of the realist movement consisted principally of a commitment to the representation of human reality. This commitment could not and did not translate itself into any precise technical or stylistic prescriptions. In so far as there were prescriptions for a specifically realist practice, these tended to be dictated by (or rationalizations of) material conditions and often to lead into contradictions. Thus a preference for visual authenticity (coupled with the non-availability of studio space) led to a lot of scenes being shot on location, both indoors and outdoors, and also to the use of non-professional actors. But a necessary corollary of this was that sound almost always had to be dubbed or post-synchronized (which was standard Italian practice for imported films anyway), and the dubbing was generally done, not by the people whose faces appeared on the screen, but by professionals. Visual style and that of the sound-tack were thus regularly at odds with one another, with the former aspiring to a strong form of realism and the latter merely mimicking ordinary dramatic illusionism.” (Pam Cook, editor, The Cinema Book, British Film Institute, 1985, 36-37)

United States

U.S. Film Noir

“As the Italian neo-realists explored the potential of real experience on film, changes were taking place in the Untied States and in Hollywood that gave rise to a style of film-making which challenged traditional Hollywood realism. A range of historical and aesthetic currents contributed to a series of crime thrillers which appeared roughly between 1945-1955, coming to be known as ‘film noir.’ Although the United States had come out of World War II on the winning side, the immediate postwar years are characterized by a mood of fear and paranoia. Sex, violence and working-class milieux characterize postwar film noir.”(Richard Armstrong, Understanding Realism, British Film Institute, 2008, 75)

“The film’s [Stranger on the Third Floor] proletarian social critique is significant and even more distinctive that that in many later noirs. Two major themes emerge in the film – its emphasis on social injustice, money, poverty, and Depression-era anxieties and the overwhelming feeling of guilt suffered by its protagonist. Social and cultural changes taking place in the United States between World War I and World War II influenced 1920s-30s American popular cultured, including social-realist theater and working-class fiction, and dealt with the dashed hopes and meager existence that so many endured in the Great Depression. Like hard-boiled detective fiction, these working-class themes flourished during a time when many were down on their luck and survived because they were willing to do the humblest work. Championing individuals, the working class hero – or anti-hero like the gangster, ex-con, tough everyman turning to crime just to survive, or the streetwise hard-boiled detective – was a man who lived by his wits and challenged corrupt institutions in a hardscrabble world. Emerging from the Depression, many ordinary people surviving in the 1930s could identify with such working-class themes.” (Sheri Chinen Biesen, Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, 25-26)

“Late in the war, Hollywood crime films became more masculine. Simulating combat and targeting a growing audience of veterans returning home from the war abroad, tough wartime noir crime film exploited violence…Publicity promoted violence and male stars beating up female costars as hard-hitting realism. The war had affected audiences, the film industry, and American culture. By the mid-1940s, publications such as the New York Times noted the graphic death and violence of the conflict itself, as well as its newsreel and photojournalism coverage, which had corresponded with a wartime psyche. World War II profoundly influenced filmmakers who enlisted – evident in the start images filmed on their return. It heightened wartime documentary newsreel production and accentuated the dramatic trend toward realism during (and after) this period. In targeting a growing male audience, studios tapped into popular conventions during the war (combat, action films with graphic, real-life naturalism) to reformulate for a postwar market. The impact of the war and war-related newsreels refined depictions of onscreen crime, violence, and increasing realism. In turn, the growing trend toward realism influenced the emerging noir crime cycle.” (Sheri Chinen Biesen, Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, 156-157)

“In general, films noirs were much more pessimistic than other films of the time. As a direct consequence, there are passages in many films noirs that rival the realism of foreign cinemas. Pessimism freed these films from the prison bars of cheery optimism and made them more in tune with a world much darker than movies could every approximate. In the context of pessimism, an element of realism was integrated into film noir. The realism is spotty, sporadic, inconsistent, but unapologetic. If the world is prone to violence, cupidity, and immorality, it is not the fault of movies with moody, philosophical underpinnings. Film noir is identifiable on the bases of its pessimistic view of the world and its realistic portrayal of this selfsame world. Indeed, often enough, realism and pessimism are indistinguishable….That films noirs are not wholly realistic should not preclude acknowledgement of the existence of a strong element of realism. In a unique period such as that during and following the second world war, the dark stylizing of film noir was perceived more as a realistic than a decorative device….But before the war there was a depression, and there was also a sense of dissatisfaction at the way films skirted the issues of the day. However, it never fully impacted against the studio’s ingrained reticence. In their morose tones, films noirs of the 1940s matched the mood of a society disrupted by the advent of war. The moodiness of this new cinema, still made within the confines of studios, inclined to manifest this vulnerability in the form of greater realism.” (Carl Richardson, Autopsy: An Element of Realism in Film Noir, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1992, 10, 32, 40-41)

Great Britain

British Spiv

“In its original sense of a ‘contact man,’ the spiv was as much a specialist as a peterman (safebreaker) or a buyer (receiver), but during the war the spiv became a sort of popular generic term for someone who dressed flashily and had underworld connections. Thus it was used to describe anyone from a barrow-boy to a gang-leader. The style of dress cam from the more fashion-conscious of the racing gangsters of the thirties – a sizeable contingent of who were Jewish or Italian with friends or relations in the rag trade….There were, more than trade union leaders, more than the politicians, the voice of the working class – busy undermining (oh, the irony) the future of their own people. The spivs, flashily displaying all the suppressed energies of the back streets, were an unconscious, dramatic protest, a form of civil disobedience that millions of English people found endearing….The pre-war underworld had been concerned either with the semi-legal activities such as gambling, drugs, and prostitution, or with the traditional criminal pursuit of robbing the rich. It was not until the war years, with the growth of commodity crime and the black market, that the underworld became parasitic on the community at large. Except for a small minority of working-class people who participated in its profits, the black market inevitably benefited the rich more than the poor by subverting a rationing system designed to ensure equal shares for all. It is in this context that one has to understand the hostility of film critics – who like most intellectuals of the period were vaguely left-of-center – to the cycle of spiv movies which flourished between 1945-1950. Ironically, the first ‘spiv film’ to draw a full barrage of criticism, They Made Me a Fugitive, was directed by the architect of Ealing realism, Alberto Cavalanti. Based on a slim expressionist novel by Jackson Budd, A Convict Has Escaped, the film marks a return to the best tradition of thirties crime thrillers, though the atmosphere is notably blacker. Cavalcanti’s skill at bringing the story to life was fully acknowledged by the critics, but he was condemned for using his talents on such a socially undesirable subject…Nevertheless, They Made Me a Fugitive was one of the top box-office pictures of 1947, and it was closely followed by two more ‘spiv films’ – It Always Rains on Sunday and Brighton Rock – which were equally popular.” (Robert Murphy, Realism and Tinsel – Cinema and Society in Britain: 1939-49, Routledge, 1992, 149-150, 151, 153, 155)

British New Wave

“Appearing at a moment of change in world cinema, the British New Wave of the 1960s chimed with attempts to push out the boundaries of representation then being practiced in Hollywood, and with bolder European attempts at cinemas of personal expression. As in Hollywood in the late 1950s, the New Wave is associated with the representation of social rebellion and sex. Drawing upon earlier traditions of realism in British cinema such as documentary, the Ealing comedy of the 1940s, Free Cinema, the New Wave also anticipated the shift from an apparently unmediated record of experience seen in Italian neo-realism, to the complex imagery of subsequent European and American film-making…If neo-realist tone of dutiful revelation lent Italian films an overall sympathy for beleaguered humanity, British New Wave directors depicted a world of men and women at war with each other… In war work during the 1940s, British women achieved a measure of economic freedom. But the 1950s saw a backlash and the retrenchment of old ideas about a woman’s place. For all their apparent liberality of representation, the New Wave films were actually deeply conformist, depicting women either as wives and mothers, or as lovers and mistresses. Women were seldom depicted as characters with their own agendas defined independently of men.” (Richard Armstrong, Understanding Realism, British Film Institute, 2008, 91, 93, 94)

British Film Noir and the New Wave

“Between 1959 and 1963, the peak period of British film production, more than one film in every three was a crime movie…Lacking the color and exoticism of Hammer horror movies and Gainsborough costume period films, the black and white B-movie world of the crime drama remained lost in a limbo between half-baked realism and lukewarm melodrama. Its claims to naturalism were dismissed, on the one hand by a Marxist orthodoxy, which saw no redeeming political merit in tales of individualist adventurism, and on the other by liberal and conservative critics who preferred not to accept an interest in crime as a feature of the national character…Nor have British crime films garnered much sympathy from feminist critics who tend to avoid their apparently patriarchal values, unsavory portrayals of women and celebrations of unreconstructed masculinity…The crime genre lends itself to the deployment of sub-textual meditations on social and philosophical issues at least as well as any other. Moreover, in its overt interest in offences against the person and property, and in the legal regulation of morality, the genre addresses key concerns and, most likely, experiences of its audience. Thus, the failure to include the crime film in discussion of social realism and the cinema during any period is misguided and it is a particularly significant omission when the New Wave realism of the late 1950s and early 1960s is being considered. Anyone familiar with writing on Britain’s New Wave will probably also be aware of the important social and political transformations that supply the context of its emergence at the close of the 1950s, such as the disappearance of the British Empire, the growth of a distinctive youth culture, the rise of working-class affluence and the revival (in the face of massive electoral success for the Conservatives) of an intellectual Left. These transformations give the New Wave texts their contradictory characteristics of nostalgia for a disappearing culture and sympathy for discontented and desiring young proletarian males. We can see these same contradictions present in the crime films of the same period, but they are given a genre specificity by the parallel transformations in Britain’s criminal underworlds and in the organization of policing…While critical attention has been focused on a handful of contemporary New Wave films that show the ripples of change spreading to the working-class communities of the Northern provinces, here clearly are movies that deal with the social earthquake at its metropolitan epicenter. These films may be thought to lie outside the privileged category of social realist cinema, but they offer invaluable insights to cultural historians interested in the ambivalent responses to the social and economic transformations of the early 1960s. The anxieties about cultural vulnerability, commercial reorganization and moral deviation that they index may be displaced into the crime movie genre and refracted through crime story conventions, but they remain near to the surface even in these underworld dramas.” (Steve Chibnall & Robert Murphy, editors, British Crime Cinema, Routledge, 1999, 98, 2, 96-97, 108)

Mexico

Mexican Cabaretera

For an excellent, albeit brief, festival of Mexican film noir, see the schedule at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, July 2015, for Mexico at Midnight: Film Noir from Mexican Cinema’s Golden Age.

J. Hoberman reviews this festival in the New York Times (July 19, 2010), Mexico at Midnight: the Perfect Match of Villains and Foils in Golden Age of Film Noir.

“In the late 1940s, Mexico experienced an economic boom that shifted the cultural and artistic energy from country life (the worn-out world of rancheras and haciendas) into the cities. Movies were inevitably affected by this trend, and Mexican filmmakers quickly responded by creating a new genre to bring the city and its multiple temptations to the masses. This genre was the cabaretera, a bizarre amalgam of music and melodrama and noir, with liberal doses of sex (especially sadism) and what we now would call high camp, set in the squalid whorehouses, cheap bars, and dark glistening streets of “sin towns” like Ciudad Juarez. Not that these were the exclusive backgrounds of the cabaretera; there’s a strong element of class conflict that also demanded contrasting wealthy environments, typically populated by hypocrites, that were just out of reach of the fallen singers and dancers who dominated these films. The cabaretera became a staple of postwar Mexican cinema and yielded many stars, but none as popular as Ninón Sevilla, a Cuban rhumba dancer who became an international success on the basis of her spirited performances in films with sleazy titles like Emilio Fernández’s Victims of Sin (1951), Alberto Gout’s Sensuality (1951), Gout’s I Don’t Deny My Past (1952), and the unquestioned masterpiece of the genre, Gout’s Aventurera (1950). Sevilla is not a typical beauty but has ferocious vivacity as both dancer and actress in a persona that dazzlingly combines innocence and sensuality. With its velvety black-and-white photography, parts of Aventurera look like film noir or Italian neo-realism, connections confirmed by the film’s fixation on crime and class struggle.” [See the article by Gary Morris in Bright Lights Film Journal (May 14, 2014), “Cinco de Mayo Fun! Cinco de Mayo Fun! Ninón Sevilla Gets Down in the 1950 Mexican Musical Melodrama Aventurera.”]

“The 1940s was the decade of the cabaretera (dance hall) film in Mexican cinema. Though similar to Hollywood’s ‘fallen woman’ film, the cabaretera was clearly a Mexican genre that incorporated aspects of the earlier ‘seduce and abandoned’ Mexican melodramas, hard-edged elements of the cine de arrabal (Mexican cinema’s urban melodramas), and popular music from the tropics: the Cuban dazon, the rumba, and the Brazilian samba. Like the Hollywood genre, Mexico’s fallen-women films emerged as response to changes in social and economic roles for women and the resulting difficulty of incorporating these changes into patriarchal discourse about female sexuality. The films of the cine de arrrabal and the cabaretera were set in the poor urban barrios of Mexico City, which were expanding as a result of the migration of campesinos into the cities in search of work. While Mexico was experiencing an unprecedented economic expansion in certain sectors of society, most people still earned their meager incomes from agricultural work. At the same time, a rapidly expanding class of workers, intellectuals, and small-business owners was struggling to make a living in overcrowded cities. Stories for these urban melodramas, often adapted from newspaper articles and popular fiction, focuses on the lives of struggling workers and their families. One of the central issues for Mexican society at this time was the increasing recognition of the failure of the Mexican Revolution to bring social and economic rewards to the lower classes, the indigenous populations, and women. The heroes of the cine de arrabal were men of these lower classes, who, according to the films, incorporated all the elements of the ‘authentic’ Mexican. They were resourceful individuals who somehow managed to rise above the constraints of poverty – morally, if not economically. While the principal characters of the cine de arrabal were male, the cabaretera films centered on a female character…Typically, the protagonists of the 1940s cabareteras were women supporting their families in one of the few lucrative positions available to them. Called ‘las ficheras,’ many of these women were in fact prostitutes. The cabaretera updated [the traditional figure] of the ‘bad woman’ in order to assimilate the Mexican working-class woman whose newfound social and economic power challenged the male’s traditional position of superiority…[T]he social and economic reorganization Mexico faced in the 1940s affected both class relations and relations between the sexes. On the one hand, Mexican women faced significant changes in all aspects of their lives, and on the other hand, nationalist discourses stressed the importance of preserving traditional values of motherhood, chastity, and obedience. These conflicting demands were difficult to negotiate for both men and women. Although the cabaretera films dramatized the tensions surrounding the roles assigned to Mexican women in the 1940s, and some even offered positive portrayals of women, at the same time the films had a difficult time providing narrative resolutions for material conflicts…The cabaretera films of this era expressed an ideological indictment of both the negative sexual aspects of machismo and the paternal authority of the state…Mexican machismo provided a link between male and state, awarding each with reciprocal support and allegiance. If the Mexican state was experiencing a ‘crisis of patriarchy,’ then this crisis could also be read as a crisis of masculinity on the individual or psychological level. In addition to the conflicted representation of women’s roles, this male crisis also emerges in the cabaretera narratives.” (Joanne Hershfield, Mexican Cinema/Mexican Woman: 1940-1950, University of Arizona Press, 1996, 77-78, 80, 83, 97)

Argentina

Argentina Film Noir

In February 2016, New York’s Museum of Modern Art held a short but highly significant festival of film noir from Argentina, Death Is My Dance Partner: Film Noir in Postwar Argentina.

The introduction to the online listing of the schedule says:

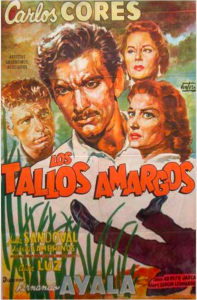

With its revelations of a darkly entertaining and uniquely indigenous brand of film noir, MoMA’s 2015 Mexico at Midnight: Film Noir from Mexican Cinema’s Golden Age series paved the way for further research into other homegrown forms of noir. A suitably sinister place to start is Argentina during the Peronist years (1949–56), a period of repression and class warfare for some, and a glorified age of social justice and national pride for others. For the screenwriters, directors, and actors in this six-film series, Buenos Aires is a cesspool of murder and corruption, where serial killers, pedophiles, and racketeers walk the streets with impunity, and no crime goes punished—the perfect backdrop for adaptations of thrillers by Cornell Woolrich, Hugo Fregonese, and Adolfo Jasca, as well as Richard Wright’sNative Son and Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou’s 1930 expressionist classic M. Taut and exciting, with perverse pleasures every step of the way, this exhibition is co-presented by its curators, Eddie Muller, founder and president of the Film Noir Foundation; and his Argentine colleague, film historian Fernando Martín Peña. Featuring the New York premieres of four films preserved by the Film Noir Foundation in association with Fernando Martín Peña, as well as the Foundation’s restoration of Los Tallos amargos (The Bitter Stems) (performed by UCLA Film & Television Archive) and the world premiere ofNative Son (digitally restored by The Library of Congress), this exhibition proves, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that we really don’t know what we’ve been missing. All film descriptions are by Eddie Muller.

On January 23, 2016, Eddie Muller, president of the Film Noir Foundation, hosted the first North American screening of Los tallos amargos at the 14th. Noir City film noir festival at San Francisco’s sold-out Castro Theater. The online program for Noir City has the following background about this Argentine classic.

Los tallos amargos (1956), a vitally significant “lost” film in the history of international noir cinema, has been restored this year by the Film Noir Foundation with the cooperation of UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association’s Charitable Trust (The HFPA Trust).

Based on the novel by journalist Adolfo Jasca, Los tallos amargos (The Bitter Stems) tells the tale of a down-on-his-luck journalist whose creation of a lucrative, if unethical, correspondence course leads to his committing the perfect murder. Although he’s never apprehended, guilt takes its ultimate toll.

The film won the Silver Condor—the Argentine Film Critics Association award to the nation’s best film in 1957, with Best Director honors going to Fernando Ayala. Forty-three years later, in 2000, American Cinematographer magazine placed the film at #49 on its list of the “Best Photographed Films of All-Time.” Despite these accolades, a 35mm print has not been available for decades, and the film is virtually unknown outside Argentina. With the FNF’s restoration, including for the first time English subtitles, this classic Argentinian noir will be returned to its rightful place in cinema history.

India

Bollywood Film Noir

On their website, “Mr. and Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!” Mrs. 55 explains why the following five Bollywood movies are Indian film noirs.

Sadhana enters a graveyard as the femme fatale of Woh Kaun Thi? (1964)

In the U.S. historians and film theorists have debated for decades about the meaning of the elusive term: “film noir.” Although many of us conjure an image of a hard-boiled detective and a mystery made more mysterious by the femme fatale, few “film noirs” actually contain these elements. This so-called genre had its roots in German Expressionism with films like Fritz Lang’s M (1931) and in depression-era crime novels. But what does the term “film noir” mean as it applies to Hindi cinema? What are the hallmarks of this genre as it played out in Bollywood and how did it begin?

I will present five films that I propose to be in the genre of Indian film noir. This is no easy task. Just as the term is vague in the American lexicon, so too does it only hazily engulf a variety of Hindi films with low-key lighting. And so I shall begin with an illustrative example. We can debate the precise definition of the genre until the end of time, but I think I can safely say that whatever Indian film noir is, Woh Kaun Thi? (1964) is Indian film noir.

Woh Kaun Thi? has 4 main basic elements. The first is in its distinct cinematographic style and setting—low-key lighting throughout a mysterious mansion and slow unhurried shots with a somber film score to match. The film gives a sense of the world being trapped in a fatalistic dream, whether alone by a graveyard or in a crowd of dancing people.

The second is the film’s overall tone and pacing—there is an uncomfortable sense of being pursued, of an impending doom unless a mystery is solved in time by the hero. Unlike in American film noir, the hero is no cynic and there is no quick sardonic dialogue to off-set the dreary mood. The hero is instead a righteous and innocent man of affairs, an heir to a fortune who becomes a victim. Though mingled with occasional musical highs, the film spirals from a slow and deliberate set-up to a climax closer and closer to complete ruin.

An interesting element of many American film noirs is the flash-back structure, which takes on an interesting form in their Indian counterparts. Woh Kaun Thi?centers around a mysterious background that occurred in the protagonist’s past life. Because the audience of Hindi films was largely composed of practicing Hindus, the world of reincarnation narrative is able to begin on a new and creatively extremely fertile ground. The hero must revisit through song, hearsay, and secrets events that took place in a past life, but whose consequences (whether karma or otherwise) now haunt him. This is the third element.

Fourthly, the film does indeed revolve around the appearance and (mis)guidance of the femme fatale, who is heard singing alluring, tragic songs. The hero is never able to wholly communicate with her, but her intentions are clearly marked with a deadly undertone. The femme fatale remains an elusive character–sometimes he chases after her, sometimes she chases after him—when her story is fully told, only then can the mystery be solved.

The films below can be placed into the category of Indian film noir along with Who Kaun Thi?:

Mahal (1949): Perhaps the grandfather of this genre, Mahal tells of a man tortured and madly in love with an apparition who haunts his mansion and claims a connection from an earlier life. The film also features the haunting vocals of Lata Mangeshkar’s all-time hit Aayega Aayega Anae Wala.

Madhubala mesmerizes Ashok Kumar in Mahal (1949)

Madhumati (1958): This classic Vijayantimala-Dilip Kumar blockbuster is told in flashback to a previous lifetime of the murder of the woman the hero still loves. The gently alluring Aajaa Re Pardesi encompasses the film’s themes of love and debts spanning several lifetimes.

Vijayantimala is reincarnated to find her lover once more in Madhumati (1958)

Bees Saal Baad (1961): A rich man comes to live in his new mansion and must solve a tragedy and murder that occurred 20 years earlier. The film contains a brilliant surprise ending, and Lata Mangeshkar scores once again with the beautiful Kahin Deep Jale, Kahin Dil.

Biswajeet follows a mysterious voice in Bees Saal Baad (1961)

Kohra (1964): This twist on Hitchcock’s Rebecca is told through the eyes of a female protagonist, living in a large, unexplored mansion that is haunted by the apparition of her husband’s first wife. Waheeda Rehman must discover the true circumstances surrounding the first wife’s death before she is driven insane. The song of the femme fatale (Jhoom Jhoom Dhalti Raat) is an absolutely genius and rare example of symbolic imagery in montage to create a feeling of horror from the song.

Waheeda Rehman sees a ghostly vision atop her mansion roof in Kohra (1964)

There are some films that contain one or more of the above elements that I have not classified as Indian film noir. These include Mera Saaya, Gumnaam, and Karz, for different reasons–often overall tone or cinematographic style. Additionally, others might argue that these films should not be categorized at all as Indian film noir, but rather as Indian gothic horror films or other such genres.

More Indian Film Noir

The website, Don’t Judge Me If You Don’t Know Me, describes 17 film noirs from India. Below are the first three, which were released during the same time period as the films discussed above by Mrs. 55. (The remaining 14 films were released in more recent decades.)

1. CID (1956), Dir: Raj Khosla

This Dev Anand and Waheeda Rehman starrer is probably the first taste of Noir film that Indian audience got, dark, brooding and atmospheric, it follows a Police officer investigating a crime and later himself getting implicated for the same, beautifully shot by Anwar and Murthy, this remains one of the best in the genre.

2. KalaPani (1958), Dir: Raj Khosla

Another Dev Anand starer directed by the same person who helmed the earlier film, this film was based on AJ Cronins book called ‘Beyond this Place’, this film is about a man who is falsely implicated for a crime he never committed and his son’s (who is a lawyer) crusade to prove his father innocent, although not as dark and atmospheric as CID this film is still able to stand on its two feet , this films crosses genres between Court room Drama and a crime thriller..and get it right.

3. Kanoon (1960), Dir: B.R.Chopra

While visiting a german film festival, B.R.Chopra was told that Indian films ‘consist nothing but songs’ so B.R.Chopra took it on himself to make a film without any song and he made Kanoon, a character driven crime drama with no protagonist..its about a hotshot public attorney who witnesses his own father in law ,who is a judge, committing a murder and having another not so innocent man framed for the same crime, things become more complicated when the public attorney have to defend the same guy who got framed for the charge in a case thats being presided by his own father in law (the judge), morals versus ambition, relationships versus deceptions, this film weaves a complex and multi layered tale of 5 characters with immaculate precision.

Bombay Noir

For a survey of this topic, see the essay, “Bombay Noir,” by Lalitha Gopalan in the anthology edited by Andrew Spicer and Helen Hanson, A Companion to Film Noir (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Spain

New Spanish Cinema and Spanish Cine Negro

“Bicycle Thief was one of the first neorealist films shown in Madrid in 1951 during the historic Italian film week that was to prove so influential for filmmakers and that was to help launch the first phase of the New Spanish Cinema in the 1950s…In contrast to Hollywood, Italian neorealism appeared in the 1950s to be a more politically effective model for challenging the escapist cinema of the Francoist regime, one that could appeal both to the Left and the Right…Although neorealism was rooted in a subversive melodrama like Luchino Visconte’s Ossessione, and although its greatest commercial successes – Roberto Rossellini’s Rome – Open City and Paisa, DeSica’s Bicycle Thief, Pietro Germi’s In the Name of the Law, and Giuseppe DeSantis’s Bitter Rice – all had strong melodramatic elements in plot, music, mise-en-scene, and morality, what had seemed so ‘new’ to critics and spectators were the realistic deviations from conventional melodrama…Neorealism seemed to provide an effective vehicle for critiquing Franco’s false picture of Spain within the national context as well as an ideal means for overcoming Spain’s isolation by expressing its unique cultural identity abroad…For many Spaniards, Italian neorealism presented a model not only of how to develop a national cinema that could challenge Hollywood’s domination of world markets but also of how such a movement could change a nation’s international image from that of a Fascist supporter of Hitler to a progressive European center of humanism…Instead of choosing one model over the other, many of the most influential Spanish filmmakers of the 1950s (whether on the Left or the Right) used neorealism and Hollywood (i.e., melodrama) as a dialectic opposition within their films…Spanish filmmakers using melodrama in the 1950s could create sudden discontinuities in mise-en-scene by shifting abruptly between Hollywood and neorealist conventions – a strategy that is most striking in Death of a Cyclist, where it is used a class discourse to reveal the Hollywood genre’s traditional alignment with the bourgeoisie…Practically everyone writing on melodrama emphasizes the centrality of the family to the genre, which is one of the reasons it had such great appeal both for a popular cinema under fascism and for an oppositional cinema forced to negotiate with Fascist censors and commercial pressures…[M]elodrama typically displaces issues of political power onto the domestic register where they are frequently transformed into generational conflicts or sexual transgression…This privileging of the relation between father and son, which was also characteristic of Fascist discourse, was dramatically foregrounded in the Spanish version of film noir (cine negro), one of the most popular new forms of melodrama to emerge in Spain during the early 1950s…[F]ilms like Post Office Box 1000 and Criminal Brigade served during this decade as one of the most effective forms of political critique for both the Left and the Right…Yet unlike Ossessione and classical Hollywood noir, Spanish cine negro does not focus on erotic desire for the woman. It expresses its cultural specificity by operating primarily as a discourse on fathers and sons. Most of the criminals become deviant because there is something wrong with their father: either he is a dead idol impossible to equal (Double-edged Crime, 1964), or too weak (Don’t Shoot Me, 1964), or too strict (The Robbers, 1961), or, if he is a good father, then he inspires heroic imitation (The Glass Eye, 1955). In these examples of cine negro, the concern is not with the son’s inheritance of private property but with his patrimonial right to wield phallic power and to embody patriarchal law. Thus, by means of political allegory, the melodramatic question, ‘Has this patriarch the right to rule over a family like ours’ was easily retranslated back into the tragic question, ‘Has this patriarch the right to rule over Spain?’” (Marsha Kinder, Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, University of California Press, 1993, 18, 25, 26, 28, 34, 40, 57, 59, 60, 61)

Japan

Japanese Noir

“By the 1960s, the noir wave that had started in America, and had been deconstructed in Europe, washed ashore in Japan. By that point, the Japanese film industry had been stripped down, essentially, to five major companies. In the essay “The Modernization of the Japanese Film Industry” the scholar Hiroshi Komatsu argues that during this period the studios were in crisis—not unlike their American counterparts, it should be noted—and that one company, the Nikkatsu Corporation, made a concerted effort to corner the market on the new “alienated youth” picture and the action film. This same atmosphere gave rise to a new kind of noir.

“Japan’s output of neo-noir (particularly from Nikkatsu, which was like the RKO of the Asian film industry) was an idiosyncratic blend of yakuza gangster picture and classic film noir. Its most famous practitioner was the wild man of Japanese noir, the director Seijun Suzuki, whose films pushed the envelope (well, destroyed the envelop and set it on fire, actually) not only of decorum and good taste but also of coherence and film language. Suzuki was hardly alone in walking the mean streets, however….

“So far I’ve mostly recommended down and dirty B movies, but no introduction to the genre would be complete without a shout out to the occasional noir output of Japan’s most heralded director, Akira Kurosawa. Though better known for samurai flicks like Yojimbo and quiet dramas like Ikiru, Kurosawa put in his time in Noirville. His three most notable excursions into this territory were High and Low, about an executive who must negotiate with a deadly kidnapper; The Bad Sleep Well, about an ordinary man hunting down his father’s killer; and Stray Dog, about a rookie cop who loses his gun to a pickpocket on a crowded bus. All three films star Kurosawa’s frequent star Toshiro Mifune, and all three take the rough materials of crime pictures and use them for the stuff of powerful drama.” (See Jake Hinkson’s post on CriminalElement.com (September 17, 2012) A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Film Noir.)

Nikkatsu Noir: The Criterion Collection – Eclipse Series 17

“From the late 1950s through the sixties, wild, idiosyncratic crime movies were the brutal and boisterous business of Nikkatsu, the oldest film studio in Japan. In an effort to attract youthful audiences growing increasingly accustomed to American and French big-screen imports, Nikkatsu began producing action potboilers (mukokuseki akushun, or “borderless action”) that incorporated elements of the western, comedy, gangster, and teen-rebel genres. This bruised and bloody collection represents a standout cross section of what Nikkatsu had to offer, from such prominent, stylistically daring directors as Seijun Suzuki, Toshio Masuda, and Takashi Nomura. (See the descriptions of the films released in The Criterion Collection: Eclipse Series 17: Nikkatsu Noir.)

South Korea

South Korean Film Noir

For a survey of this topic, see the essay, “Film Noir in Asia: Historicizing South Korean Crime Thrillers,” by Nikki J. Y. Lee and Julian Stringer in the anthology edited by Andrew Spicer and Helen Hanson, A Companion to Film Noir (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Addendum

Each of the following books has extensive references to film noirs of many countries.

John Grant, A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir, Limelight Editions, 2013. (Of any current film noir book, this has the largest filmography, from silent films to today, and it covers the most countries. Provides full film credits, as well as plot descriptions and evaluations, which vary from from brief to lengthy.)

Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer, editors, International Noir (Traditions in World Cinema Eup), Edinburgh University Press, 2014. (Examines film noir’s influence on the cinematic traditions of Britain, France, Scandinavia, Japan, Hong Kong, Korea, and India. A filmography of titles, with directors and dates of release, which is divided by country, with subcategories principally organized by time, such as silent era, postwar, neo-noir, new wave, and recent decades.)

Spencer Selby, The Worldwide Film Noir Tradition, Sink Press, 2013. (A filmography, with key film credits and short plot descriptions of film noir for countries around the world.)

Andrew Spicer, Historical Dictionary of Film Noir, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2010. (A filmography of titles, with directors and dates of release, of film noir and frequently neo-noir for countries all around the world. Also a bibliography about film noir for many countries.)

Andrew Spicer and Helen Hanson, A Companion to Film Noir (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013). In addition to essays specific to film noir in “Asia” (South Korea) and India (Bombay), there are other essays in which film noirs in other countries are discussed.

The following books focus on film noir in France, Britain and Europe, respectively. They provide much greater in-depth analyses than the volumes cited above.

Robin Buss, French Film Noir, Marion Boyars, 2001 [1994]. (Includes a filmography, with full credits for each film and a plot description.)

Michael F. Keaney, British Film Noir Guide, McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008. (Each film has key film credits, a plot description and the author’s evaluation and rating. There are also several valuable appendices.)

Andrew Spicer, editor, European film noir, Manchester University Press, 2007. (Essays on film noir as well as neo-noir for France, Britain, Germany, and Spain, and noir only for Italy. Each essay concludes with a filmography, with directors and dates of release.)

Also:

Steve Chibnall and Robert Murhpy, editors, British Crime Cinema, Routledge, 1999. (As indicated by the title, this book is not explicitly about British film noir. However, many essays pertain to British film noirs. There is a filmography from 1939-1997, with key credits for each film.)

Jennifer Fay and Justus Nieland, Film Noir: Hard-Boiled Modernity and the Cultures of Globalization (Routledge, 2010). (This book traces film noir’s emergent connection to European cinema, its movement within a cosmopolitan culture of literary and cinematic translation, and its postwar consolidation in the US, Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America.)