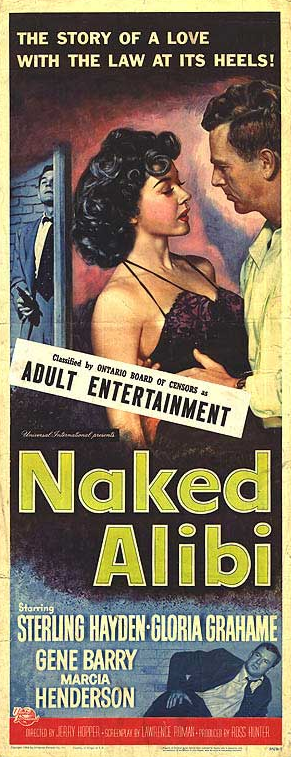

Naked Alibi

Introduction

The reason why Gloria Graham, a noir icon, is not mentioned below is because the focus of my analysis of Naked Alibi is about film noir and Cold War politics during the McCarthy era.

Main Credits

Director: Jerry Hopper. Screenplay: Lawrence Roman based on a story, “Cry Copper,” by J. Robert Bren and Gladys Atwater. Producer: Ross Hunter. Cinematographer: Russell Metty. Original Music (un-credited): Hans J. Salter and Frank Skinner. Art Directors: Alexander Golitzen, Emrich Nicholson. Editor: Al Clark. Cast: Sterling Hayden (Chief Joe Conroy), Gloria Graham (Marlene), Gene Barry (Al Willis), Marcia Henderson (Helen Willis). Released: Universal International, January 14, 1955. 86 minutes.

Presentation

The following summary of Naked Alibi by Michael F. Keaney (Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959, McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), which I have shortened, ends with a question whose answer can be derived from the summary itself (i.e., without even watching the movie) by using either or both of two different, but complementary, political analyses that relate to this film noir.

The following summary of Naked Alibi by Michael F. Keaney (Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959, McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), which I have shortened, ends with a question whose answer can be derived from the summary itself (i.e., without even watching the movie) by using either or both of two different, but complementary, political analyses that relate to this film noir.

“Somebody has killed three detectives, and the police chief (Sterling Hayden) suspects a baker (Gene Barry) who threatened one of the cops after they had arrested him for being drunk and disorderly. Determined to prove Barry’s guilt, Hayden gets tough with the baker and is later fired for police brutality. Hayden begins following the suspect. Unable to take the pressure, Barry leaves his wife and baby and flees to a Mexican border town, where a sexy cantina singer (Gloria Graham) has been waiting for him. Guilty of adultery, yes, but is Barry the vicious cop killer?” (293-294)

Dennis Broe (Film Noir, American Workers, and Postwar Hollywood, University Press of Florida, 2009) cites 14 film noirs, released from 1953 to 1958, in the category Vigilante Cop. In these films, he says:

Dennis Broe (Film Noir, American Workers, and Postwar Hollywood, University Press of Florida, 2009) cites 14 film noirs, released from 1953 to 1958, in the category Vigilante Cop. In these films, he says:

“The cop goes outside the law not as a fugitive but in order to better enforce the law [and to get] revenge…The intuitive investigation of the hard-boiled detective and the scientific deduction of the procedural are replaced here by an investigative technique that ‘consists of beating up the suspects to force confessions’” (p. 101, with a quote from John Cawelti’s Adventure, Mystery and Romance: Formula Stories as Art and Popular Culture, University of Chicago Press, 1976, 188).

Broe claims that the vigilante cop’s violence “is rationalized by the cop’s righteous indignation.” He continues:

“The violence might be read as an unacknowledged rage by a now immobile working class that has traded its right to contest both its role in the process of production and the larger direction in which the society is moving for a few pieces of silver in the form of more commodities and a more affluent lifestyle.” (102)

However, by associating violence by vigilante cops with rage by the working class, Broe contradicts himself. When he first defines the “McCarthyite crime film,” he says:

“The protagonists of the…police procedural were often working-class cops who surveyed and policed neighborhoods that had previously hidden the sympathetic fugitive. There was a rough progression whereby the cop-hero at first reverted back to a fugitive (Where the Sidewalk Ends, 1950), then moved inside the law (Detective Story, 1951), and finally journeyed outside the law, this time not as lawbreaker but as vigilante, as supra-representative of the forces of order (Big Heat, 1953).” (81)

In each example of this “progression” within the McCarthyite crime film, the behavior of cops isn’t supposed to be associated with that of the working class. On the contrary, the crux of Broe’s analysis of film noir is that there is a contrast between criminals and cops, and criminals represent the working class.

Broe’s analysis suffers from two flaws. First, his basis for dividing film noir into two key periods (1945-1950 and 1950-1955) is fundamentally mono-causal. “[F]ilm noir is primarily an expression of class, and particularly of postwar American class tensions and class struggle.” (p. xviii) Second, each period is associated with a single political ideology, first left-wing and then right-wing.

While his analysis is fascinating and informative, its lack of nuance is shown by his error in conflating violence by vigilante cops with rage by the working class. As Broe suggests, a violence in vigilante cops that is “righteous” would be politically associated with the radical right. But to have the working class feel rage because it gave up waging class struggle for the spoils of the Affluent Society would be associated with the far left. Violence in these vigilante cop film noirs cannot simultaneously be associated with opposite ends of the political spectrum.

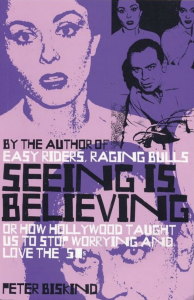

In contrast, Peter Biskind (Seeing Is Believing, Pantheon Books, 1983) explicitly differentiates films in this period across the entire political spectrum: left-wing, liberal, conservative, and right-wing. He teases out the ways in which crime films – as well as westerns, sci-fi flicks, family melodramas, juvenile delinquent and military dramas – represent one or another of these four political ideologies in the McCarthy era. (For extensive background about the economic bases and Cold War activities of these four political camps, which corroborate Biskind’s perspectives, see the first of the three parts of Franz Schurmann’s magisterial The Logic of World Power, Pantheon Books, 1974.)

In contrast, Peter Biskind (Seeing Is Believing, Pantheon Books, 1983) explicitly differentiates films in this period across the entire political spectrum: left-wing, liberal, conservative, and right-wing. He teases out the ways in which crime films – as well as westerns, sci-fi flicks, family melodramas, juvenile delinquent and military dramas – represent one or another of these four political ideologies in the McCarthy era. (For extensive background about the economic bases and Cold War activities of these four political camps, which corroborate Biskind’s perspectives, see the first of the three parts of Franz Schurmann’s magisterial The Logic of World Power, Pantheon Books, 1974.)

The category in Biskind’s book that pertains to Naked Alibi is called, “The Enemy Within,” and all of the films in this category “set out to solve the same problem: social control.”

First, he discusses On the Waterfront as a “corporate-liberal crime film,” which “offers us the informer as saint,” where “the schoolboy injunction against informing is relative, not absolute. Moral absolutes are, after all, the coin of extremism.” (179, 181)

Next, he explains Underworld USA as a “conservative gangster film of the fifties,” in which “informing is not pitted against loyalty, as it is in On the Waterfront; it is precisely loyalty to friends and family that motivates informing…Whereas in corporate-liberal films, only by acting in the public interest can the hero satisfy his private needs, in conservative films, only by acting in his own interests can he satisfy public needs…Whereas corporate-liberal films either repudiate or reform revenge heroes, conservative films accommodate them.” (186, 188)

Next, he explains Underworld USA as a “conservative gangster film of the fifties,” in which “informing is not pitted against loyalty, as it is in On the Waterfront; it is precisely loyalty to friends and family that motivates informing…Whereas in corporate-liberal films, only by acting in the public interest can the hero satisfy his private needs, in conservative films, only by acting in his own interests can he satisfy public needs…Whereas corporate-liberal films either repudiate or reform revenge heroes, conservative films accommodate them.” (186, 188)

In right-wing films, however, “revenge is a perfectly adequate motive.” Biskind’s example is The Big Heat, which “endorses the use of force, the exercise of power, but it is force deployed against the center [i.e., conservatives and liberals]. Only by taking the law into his own hands can Bannion [Glenn Ford] purge society.” (192, 193) Just like Sterling Hayden does in Naked Alibi.

Given its year of release and its plot, even as briefly sketched by Keaney, and based on the analyses by Broe and Biskind, the answer to Keaney’s question must be affirmative. Barry is indeed a vicious cop killer. When the police commissioner asks Hayden if he has any proof against Barry, Hayden answers, “Just give me a little time with him and I’ll have all the proof you need.”

Because Naked Alibi is a vigilante cop film (Broe) and a right-wing film in which force is endorsed in order to maintain social control (Biskind), Hayden’s gut feelings about Barry’s guilt are, of course, vindicated. Earlier issues in the plot, such as Hayden’s dismissal from the force and an investigation into brutality in the police department, are forgotten.

Biskind’s example of a 1950s left-wing crime film is Force of Evil. However, unlike his other selections, this film is not concerned with informing or confessing. Therefore, instead, I want to consider a film in which key themes are whether a person should confess as well as the interrogation methods used to make people confess. The interrogation methods are not “beating up the suspects to force confessions.” Nonetheless, the film conveys the methods used to extract confessions as unjust if not illegal.

For decades, despite its title and year of release (1953), Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess has not been written up in film noir books as a crime film that is politically engaged with McCarthyism. Instead, its plot has mistakenly been dealt with in terms of religion. Whether these books have been published many years ago or recently, or whether they have been written for a broad or a specialized readership, they have failed to address the displacement of McCarthyism in the film.

For example, Eddie Muller (Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir, St. Martin’s Press, 1998) says that I Confess “raised to metaphysical heights Hitchcock’s perennial theme of a lone person facing down an unjust fate…It clearly pitted a system of fallible human justice against the conceit of God’s divine plan.” (126)

In Film Noir: The Encyclopedia (Overlook Duckworth, 2010) Glenn Erickson says that “Hitchcock’s ‘devout noir’ manipulates characters and narrative to maintain the theme of a priest humbling himself before a heavenly law higher than man’s.” (143)

Properly eschewing such ahistorical and unpolitical interpretations, an essay by Robert Genter, “Cold War Confessions and the Trauma of McCarthyism: Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess and The Wrong Man” (Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 29:2, 2012) contextualizes I Confess not as a meditation on moral issues of conscience within Catholicism but rather, through sophisticated displacement via a romantic drama set in Quebec City, as a critique of the “relentless interrogation of witnesses, whether such interrogations occurred in front of congressional committees or in the back rooms of police stations…Hitchcock’s criticisms of interrogation tactics in this pre-Miranda landscape echoed the criticisms the Warren Court would make several years later.” (132, 133).

Genter adds:

“In particular, Hitchcock foregrounds the relentless questioning by Inspector Larrue [Karl Malden] of Ruth Grandfort [Anne Baxter] who is forced…to testify to her previous love affair [with Father Logan (Montgomery Clift)]” in front of her husband. “On the verge of tears, Ruth asks Larrue: ‘Are you a human being, Inspector?’” (133)

In the 1950s, Genter says:

“[There was] a litany of police interrogation manuals such as Fundamentals of Criminal Investigation [which told authorities to] ‘interrogate steadily and without relent, leaving the subject with no prospect of surcease’ [and to use] ‘emotional appeals and tricks,’ practices that Hitchcock, and later the Warren Court, found both unconstitutional and inhumane.” (133)

For Elia Kazan, the director of On the Waterfront, who in 1952 infamously named eight former Group Theater members as one-time Communists to the House Un-American Activities Committee, Marlon Brando is, in Biskind’s description, “the informer as saint.” For Hitchcock, Clift is a paragon for refusing to give up the name of a murderer. The title of the film, therefore, is paradoxical because Father Logan’s stance toward Inspector Larrue is, “I won’t confess.”

“Moral absolutes are, after all, the coin of extremism,” Biskind writes (181). Logan’s moral conviction to honor the sanctity of the confessional establishes the political viewpoint, via displacement, of the film’s antagonism toward the associated practices used for witch hunting by the U.S. government and for extracting confessions by law enforcement. Once the displacement is unpackaged, I Confess is a significant leftist film.

Since Broe does not acknowledge an anti-McCarthyite crime film, he cannot, by definition, discuss left-wing film noirs of the 1950s. But these films exist, like I Confess (and Force of Evil). As in Naked Alibi, the police play rough. However, instead of the suspect (Barry) being actually guilty, and the vigilante cop (Hayden) triumphant, the accused (Clift) is innocent, and the interrogation methods used by the agent of the law (Malden) are scorned.

The last film named in Broe’s category, Vigilante Cop, is Touch of Evil, although he says nothing about it in his book. Because Touch of Evil is a McCarthyite crime film, its politics for Broe, therefore, are right-wing.

However, as Carl Richardson explains in Autopsy (The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1992), the vigilante cop in Touch of Evil, Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles), is modeled in multiple ways on Joe McCarthy. That is, Touch of Evil is an anti-McCarthyite crime film. Quoting from an interview with Welles, Richardson says:

However, as Carl Richardson explains in Autopsy (The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1992), the vigilante cop in Touch of Evil, Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles), is modeled in multiple ways on Joe McCarthy. That is, Touch of Evil is an anti-McCarthyite crime film. Quoting from an interview with Welles, Richardson says:

“Reverberations of anti-McCarthyism echo in Welles’s personal assessment of Hank Quinlan, who ‘does not want to submit the guilty ones to justice so much as to assassinate them in the name of the law, using the police for his own purposes; and this is a fascist scenario, a totalitarian scenario, contrary to traditional law and human justice.’” (138)

Because Touch of Evil and Naked Alibi are on the opposite sides of the political spectrum, it should be unsurprising that the conclusion of each film is diametrically different. Naked Alibi ends with confirmation of Hayden’s heroic status. In the last shot, with the camera high overhead, Hayden walks off alone into the night while the background music swells.

In the finale of Touch of Evil, Orson Welles tells his partner, who is secretly taping the confession, that for years he has falsified evidence against suspects. (“Aiding justice,” he says.) After Welles realizes that he has been set up, he shoots his partner, but his partner lives long enough to fire back and kill Welles. Rather than being a hero (as in a right-wing film), Welles is an enemy of fair judicial procedure (because this is a left-wing film). Instead of striding away victorious, like Hayden, Welles is vanquished and floating dead in the polluted water of a shallow canal beneath oil derricks on the outskirts of town.

Broe has done a service in relating politics in film noir with the experiences of the postwar working class. Nonetheless, comparisons of Naked Alibi with I Confess and Touch of Evil show that the work of political analysis of film noir must be more nuanced. Essential aspects in this endeavor are recognizing and interpreting displacement, taking proper account of historical context, and carefully assessing plot and characters to discern the appropriate political ideology among a range of possibilities.