No Man of Her Own

Introduction

The text in the Presentation below is based on my plot summary and commentary about No Man of Her Own, as published in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia (Overlook Duckworth, 2010, 212-213). It has been reformatted into shorter paragraphs. (It also represents my final submission to the editors, which includes, among other omissions in the printed version, a reference to the novella, “They Call Me Patrice.”)

Afterwards, in Addendum I, I critique Mark Osteen’s analysis of No Man of Her Own, which is included in his book, Nightmare Alley: Film Noir and the American Dream (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

Afterwards, in Addendum I, I critique Mark Osteen’s analysis of No Man of Her Own, which is included in his book, Nightmare Alley: Film Noir and the American Dream (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

Osteen’s interpretation is at odds with my own. However, it is severely flawed because, among other reasons, he fails to provide a complete history of the film’s source material, and he inaccurately explains important details of the plot. Furthermore, it is based on the film noir hardboiled paradigm. As I will show, No Man of Her Own cannot be analyzed successfully in terms of this paradigm. Also, therefore, Osteen’s assessments of three key issues in the film (marriage, class mobility and the American Dream) are easily challenged.

Main Credits

Director: Mitchell Leisen. Screenplay: Sally Benson, Catherine Turney (Mitchell Leisen, uncredited) based on the novel I Married a Dead Man by William Irish [Cornell Woolrich] and the novella “They Call Me Patrice” by William Irish [Cornell Woolrich]. Producer: Richard Maibaum. Director of Photography: Daniel L. Fapp. Music: Hugo Friedhofer. Art Directors: Henry Bumstead, Hans Dreier. Editor: Alma Macrorie. Cast: Barbara Stanwyck (Helen Ferguson/Patrice Harkness), John Lund (Bill Harkness), Jane Cowl (Mrs. Harkness), Phyllis Thaxter (Patrice Harkness), Lyle Bettger (Stephen Morley), Henry O’Neill (Mr. Harkness), Richard Denning (Hugh Harkness), Carole Mathews (Blonde), Harry Antrim (Ty Winthrop), Catherine Craig (Rosalie Baker), Esther Dale (Josie), Milburn Stone (Plainclothesman), Griff Barnett (Dr. Parker). Released: Paramount, February 21, 1950. 98 minutes.

From Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

Plot Summary

Helen, broke and pregnant, stands outside Stephen’s cheap apartment and begs him to take her back. Instead, he pushes a railroad ticket under the door. Inside, his girlfriend warns him never to brush her off like that.

Helen takes the train and meets Patrice and Hugh. Patrice is also pregnant, and Hugh’s parents have never seen her. As a favor, Helen puts on Patrice’s ring. The train suddenly crashes, and Patrice and Hugh die. Because Helen is identified as Patrice by the ring, Hugh’s family pays for the best hospital care for Helen and her baby. Desperate to give her child a better life, Helen goes to live with Hugh’s parents and his brother, Bill. Helen and Bill fall in love. Stephen, discovering Helen is alive, locates her and blackmails her into marrying him. Her parents-in-law will soon die, and Stephen wants a share of Helen’s inheritance. Before Helen fires a gun at Stephen, he looks lifeless. Bill helps her get rid of the corpse. Afterwards, Helen and Bill are tormented by the murder. When the police come to their house, Helen confesses. However, her bullet missed and Stephen was already dead, killed by his girlfriend.

Commentary

Stephen dumped Helen, and Hugh, whose ring she wears, was not her husband. So until Bill says he loves her, Helen has not had a man of her own. In the scene after they kiss, Helen is atop a ladder removing ornaments from a Christmas tree. It is halfway through the film, and it brings to a head both a romantic storyline and the classic visual style.

The classic style reinforces Helen’s “perfect peace and security” in the Harkness’s home. For example, although Bill does not believe Helen is his sister-in-law, when she commits telltale errors, the visual style remains classic. Were Bill going to expose Helen as an imposter, the style would turn noir. While Helen is up on the ladder, she finds out someone (Stephen) knows who she really is, and she collapses. Thereafter, a crime story (blackmail and murder) supersedes the love story, and the noir visual style eclipses the classic.

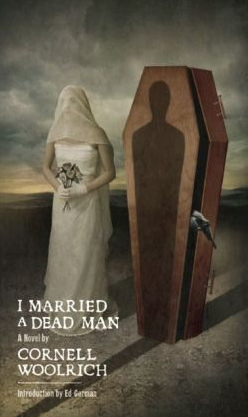

When Helen is cleared of killing Stephen, her blissful suburban life is restored. This follows the ending of Cornell Woolrich’s novella, “They Call Me Patrice,” published in Today’s Woman magazine in April 1946. In contrast, his novel, I Married a Dead Man, based on the novella and published two years later, ends with Helen and Bill’s romance ruined because each suspects the other murdered Stephen.

No Man of Her Own is a film noir although it does not have the bleak conclusion of I Married a Dead Man. The difference in their endings derives from the mutually exclusive ways noir and melodrama deal with Helen’s social origins and opportunities.

Since Stephen personifies noir’s inescapable dark past, he must also personify the wrong side of the tracks, where he and Helen come from. Because of noir’s determinism (and, therefore, its conservatism), Stephen/her past/her background will topple Helen from her accidental lift up the social ladder.

In melodrama, Stephen is simply an invader into an idyllic suburb. The past – Helen’s class – will not stop her climb. In melodrama, whether seen as naïve or progressive, unexpected upward social mobility, rags to riches, is conventional. Both the film and novel depict a nightmarish way for a penniless, pregnant, unmarried woman to achieve a postwar American dream — a loving family in a large, “warm and friendly” home. Namely, she should survive a freak train wreck that takes scores of innocent lives.

In melodrama, Helen’s fine character redeems such a deus ex machina. Her replacement of Patrice shows the ease with which class differences can be effaced. In noir, Helen’s qualities are irrelevant. The final scene underscores how melodrama, as opposed to noir, does not circumscribe people’s fates to the cards they were dealt. Helen’s voice-over, lauding the charms of her home, speaks for her kind of woman, who deserves to have the good life as much as a woman born to it, like the real Patrice.

Addendum I: A Critique of Mark Osteen’s Analysis of No Man of Her Own

Mark Osteen begins his analysis as follows.

“My Name Is Julia Ross (written by Muriel Roy Bolton) and No Man of Her Own (scripted by Catherine Turney and Sally Benson) use their Gothic plots to suggest that all married women undergo identity conversions. Though each film supplies a conventional Hollywood ending, complete with a happy couple, their critiques of marriage and gender roles linger beyond their perfunctory conclusions. Each film scrutinizes the dream of social mobility, as their struggling lower-class protagonists are thrust into the upper class, surviving only through lies and violence. The films question the central institution of middle-class society and cast doubt on the American mythos of infinite class mobility.” (58)

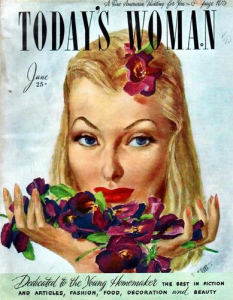

Osteen notes that Benson and Turney based their screenplay on the novel I Married a Dead Man by Cornell Woolrich (writing as William Irish). However, Osteen never refers to the origin of the novel, “They Call Me Patrice,” a novella by Woolrich, which was published two years earlier in Today’s Woman magazine in April 1946.

This is a glaring omission because Osteen places great stock in his analysis of No Man of Her Own in the differences between drafts of the screenplay and the “finished film.” The conclusion of the film conforms to the novella, not the novel or early versions of the screenplay (when the film was called With This Ring and then The Lie). Had Osteen acknowledged the existence of the novella, he would have had to account for the difference between its conclusion and the novel’s. Consequently, his analysis of the film would have had to be different.

Osteen also makes mistakes in basic interpretation of what happens in the film, as well as grievous errors of plot description. For example, he fails to properly account for Bill’s behavior toward Helen. He says, “Helen almost ruins it all while shopping with Bill (John Lund), who has taken a shine to her. Trying out a new pen, she unthinkingly writes, ‘Helen F.,’ before stopping in horror. Bill looks at her peculiarly; later we learn that he has suspected all along she isn’t really Patrice.” (61-62)

If Bill has suspected the truth all along, then it makes no sense to say that Helen could have “almost” revealed herself as an impersonator. There is nothing Helen can do to give herself away because Bill already doesn’t believe she is really Patrice, and he doesn’t care. In fact, after Bill and Helen get rid of Steve’s corpse, he tells her that, although he knew her secret “almost from the beginning,” he never wanted to give her away. He says, “I was afraid I’d lose you. That you’d walk out.”

Furthermore, Osteen misrepresents what occurs in the shopping scene. Previously, Bill has seen Helen make mistakes, such as failing to recognize Hugh’s favorite song when he plays it on the piano at the house. Mrs. Harkness dismisses the incident as a result of the train wreck and the death of Hugh. She says, “It’s a wonder you remember anything after what you’ve been through.”

In the following scene, Bill wants to buy a nice fountain pen as a Christmas gift for his father. While he is testing a pen, his facial expression shows that he has suddenly gotten an idea. He hands the pen to Helen and says, “Patrice, how do you like the way this one writes?” Helen takes the pen and writes “Helen F” on a pad of paper. As Osteen says, Helen stops “in horror.” But Osteen is wrong to say, “Bill looks at her peculiarly.” Bill sees what Helen has written, but he says nothing. He has tested Helen, and he has confirmed his suspicion about her. However, Bill doesn’t let on to Helen about his discovery. Instead, he covers up for her mistake by telling the store clerk he isn’t satisfied with the pen and asking if he could try a different one.

Contrary to what Osteen says, it isn’t “later we learn that he has suspected all along she isn’t really Patrice.” This is the scene that reveals Bill has already figured out Helen is not his sister-in-law.

Furthermore, in the novel, after the incident with the fountain pen in the store, the last two pages in the chapter are about Helen’s wondering whether Bill had deliberately tested her or not. Then she discovers evidence that leads her to conclude, “It had been a test, all right.” (Chapter 21)

In the film, immediately after Bill and Helen leave the store, a woman approaches a clerk and says, “Cigarette lighters. Gold.” She is Steve’s girlfriend. Not only do we now know that Bill has seen through Helen’s ruse, we also are aware that Steve is in Caulfield.

In the next scene, at the Harkness’s home, Bill is about to tell his father what he has learned. “I ran into Patrice downtown today. Something funny happened.” Before he can do so, his mother enters the room and talks about how much she adores Helen and, when Bill marries, she hopes he “brings home someone half as nice.” When they are alone again, Bill’s father asks him what it was he had wanted to say. Bill replies that he must have forgotten. Mr. Harkness says, “You’re getting as bad as your mother.” Bill mutters, “Yeah, I guess I am.” That is, he is coming to share with his mother a love for Helen.

Bill’s affection for Helen increases when she refuses to agree to a change in Mr. Harkness’s will. After what Mrs. Harkness would receive, the revised will would assign one-quarter of “the residue” to Bill and three-quarters to Helen. (Bill would assume control of his father’s business, so he would still be well provided for.) After Helen rushes out of the room, Bill, smiling, asks his father to sign the will. Helen, Bill recognizes, isn’t a gold-digger. He goes up to her room, thanks her for the way she acted, and asks her to “shake hands good night.”

Just before New Year’s Eve, Mr. and Mrs. Harkness, as well as Helen and Bill, are standing on the front porch of their house listening to carolers. Bill takes Helen aside in the shadows and kisses her. Mrs. Harkness, off camera, promptly makes up reason why she and Mr. Harkness need to go back inside. When her husband objects that he’ll never get pneumonia, she counters, “You’ll get worse than pneumonia if you don’t stop being so thick-headed.” Mrs. Harkness is wise to what is happening and, as she looks back at the couple before closing the front door, it is evident that she approves of what she sees.

Nothing so far is close to being a film noir. It is all romantic melodrama. In the next scene Helen is taking down ornaments from the family’s Christmas tree. As I note in my commentary in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia, it is halfway through the film and, from this point forward, film noir – in plot and visual style – takes over from romantic melodrama.

Osteen says, “Both novel and film thus ask whether class…is merely a fiction based on expectation and belief. After all, if a nobody like Helen Ferguson can pass herself off as a member of the elite, then social class must be no more than a masquerade. Or is there some essence that members of the elite recognize in each other that an imposter can never duplicate?” (62)

From what actually occurs in the film, Osteen’s interpretation of class mobility isn’t plausible. Helen, as even Osteen acknowledges, doesn’t deceive Bill. Because Helen fails to “pass herself off as a member of the elite,” Osteen lacks any evidence that “social class must be no more than a masquerade.”

Helen experiences social mobility, but not, as Osteen claims, because the film intends to show that she can successfully counterfeit herself as a member of the elite and, therefore, that class is fluid because it is a fiction, smoke and mirrors, an unreal category.

Osteen is correct to say that “the train has become her vehicle for upward social mobility.” Helen takes advantage of accidental circumstances that enable her to move up in the world for only one reason, the benefits for her child. The most critical of these is that her boy will get a home.

In the novel, at the very end of the chapter in which Helen is about to be released from the hospital, she almost tells her doctor the truth because she thinks she “can’t do it” (i.e., continue the deception). The doctor lifts up her baby and says, “You want him to have a home, don’t you?…‘Yes,’ she said submissively, ‘Yes, I want him to have a home.’” (Chapter 12) In the film Helen’s anguish that she “can’t go through with it” occurs on the train as it pulls into the Caulfield station. Through the train car window Helen sees Mrs. Harkness waving to her. Helen is holding her baby. She looks down at the child and says, “For you. For you.”

In the novella, the emphasis on home is so strong that both these events occur. In the hospital, the doctor lifts up her baby and says, “You want to take him home, don’t you? You don’t want him to grow up in a hospital?’ He laughed at her teasingly. You want him to have a home, don’t you?’ She held the baby to her. ‘Yes,’ she said at last, submissively. ‘Yes, I want him to have a home.’” (132) And as the train pulls into the Caulfield railroad station, “There was a woman looking right at her. Their eyes met, locked, held fast…The woman pointed to her…The girl held the baby near the window and the woman outside raised her hand and waved…The girl holding the baby put her head down close to his, almost as if averting it from the window…’For you,’ she breathed. ‘For you. And God forgive me.’” (132, 133)

Helen’s social ascent is not something she willfully pulls off through deceit. It is allowed to her because Bill is drawn to her, the woman she really is, not because she has artificially re-made herself as a member of the elite. As I say in my commentary in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia, Helen’s social mobility, via the train wreck and her own good character, are aspects of a romantic melodrama rather than a film noir.

Here is the fundamental difference between my perspective and Mark Osteen’s. I see the film conveying two kinds of narratives, romantic melodrama and film noir. Osteen analyzes the plot only within the framework of the film noir hardboiled paradigm. The failings of his analysis derive, in no small measure, from the limitations of this framework to interpret a film like No Man of Her Own.

The inappropriateness of the hardboiled paradigm is evident, for example, in the way Osteen sees the meaning of Helen and Bill dumping Steve’s corpse into an empty railroad car as it passes through Caulfield. He writes, “Initially the vehicle for the film’s social mobility metaphor, the train now sardonically comments on Helen’s American dream: yes, you can move into the upper class but only by leaving a trail of bodies behind you.” (63)

The train wreck, however, is Helen’s actual – not metaphorical – means of class ascent. As for the connection between the train that carries off Steve’s dead body and Helen’s social mobility, it can only be valid if Helen has any responsibility for Steve’s death. Alleging that she does, Osteen claims that No Man of Her Own critiques marriage, social mobility and the American Dream. However, his interpretation of the film fails because, as I explain below, his account of Steve’s murder is dead wrong. Osteen says:

“[T]he beginning of the film takes place three months after the major events. Helen (as Patrice) and Bill have married, but their guilty secret [i.e., that one of them murdered Steve] drives a wedge between them and prevents them from enjoying their comfortable upper-class life. At the film’s opening, ‘Patrice’ tells us in voice-over that the summer nights in Caulfield, where they live, are pleasant, ‘but not for us.’ Their fulfillment of the American Dream is tainted by the crimes and compromises committed to obtain it; their beautiful street is really a nightmare alley.” (64)

However, Osteen doesn’t mention that No Man of Her Own, whose plot unspools through a flashback, ends with another voice-over by Helen. In the final scene of the film, she says, “The house we live in is so beautiful. What stood between us is gone now. Whatever comes we can face together.”

Contrary to Osteen’s view, Helen and Bill have committed no crimes. Helen’s pretense to be Patrice is forgiven by Bill, and also by Mrs. Harkness. By selectively stating what occurs in the film (such as only citing Helen’s first voice-over), Osteen gives an interpretation of No Man of Her Own that is in accord with the film noir hardboiled paradigm, as well as the title of his book, Nightmare Alley. But the film’s actual ending shows that Helen and Bill’s marriage is rock solid, Helen has achieved upward social mobility, and she has realized the American Dream.

Osteen completes his analysis of the film as follows.

“Woolrich’s vision, then, is much darker, implying not only that this marriage is a lie but that marriage itself is a tissue of formalities, the American Dream a counterfeit. Even the film’s unlikely coincidences and hastily wrapped-up happy ending leave intact its critical analysis of marriage and its warning about the dream of social mobility. Helen gets away with her subterfuge, but several people die. All versions thus imply that you may change your identity, but the price is steep; the loss of your moral and existential center and the sacrifice of anyone who knows who you are – including yourself.” (64-65)

Helen, as I have noted, does not “get away with her subterfuge.” Bill is on to her from the start. He falls in love with her for the good person that she is, and he lets her think she is deceiving him. Osteen is wrong to say “all versions” imply the same thing about changing one’s identity. The film’s ending conforms to the “happy ending” Woolrich wrote for the novella, “They Call Me Patrice,” the original version of the story that Osteen never mentions.

Osteen doesn’t satisfactorily explain why the film has a different ending from the novel. What matters to him is that the ending weakens what he believes the film should really be about, namely the same dark vision of marriage, social mobility and the American Dream that he finds in Woolrich’s novel.

However, there is another explanation why the endings in the film and the novel are different. In fact, considering the history of the story, the reason for the difference seems obvious. Sally Benson and Catherine Turney, the scriptwriters, may have deliberately wanted the conclusion of the film to be more positive for its intended audience: women. The conclusion that they used was already at hand in the novella, “They Call Me Patrice.”

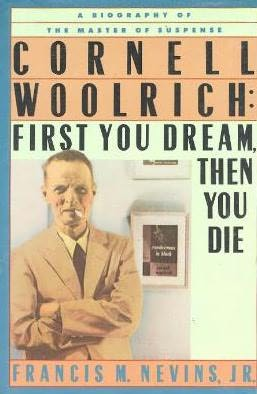

It is important to note that the novella was not published in a crime-pulp magazine. Other than the general pulp magazine, Argosy, during Woolrich’s most productive years, 1934-1947, the overwhelming majority of his short fiction was published in crime-pulp magazines like Black Mask, Detective Fiction Magazine, Detective Fiction Weekly, Detective Tales, Dime Detective, Dime Mystery, Double Detective, Fynn’s Detective Magazine, Mystery Book Magazine, Pocket Detective, and Street & Smith’s Detective Story. (See Francis M. Nevins, Jr., Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die [Mysterious Press, 1988, 530-551] and RARA-AVIS: Bibliographies: Cornell Woolrich.)

Working class men consumed these magazines, as several historians have shown, such as Erin A. Smith (Hard-Boiled: Working-Class Readers and Pulp Magazines, Temple University Press, 2000) and Christopher Breu (Hard-Boiled Masculinities, University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

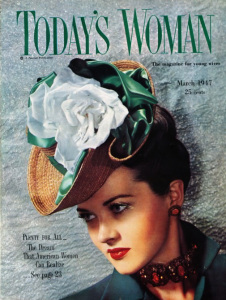

During the period of his greatest output of work, Woolrich published outside of crime-pulp (i.e., men’s) magazines on just two occasions. “The Girl Who Married Royalty” appeared in Good Housekeeping (March 1945) and “They Call Me Patrice” in Today’s Woman (April 1946). It stands to reason that Woolrich submitted these stories to women’s magazines because he recognized that they were more suitable for a female audience than the readership for crime-pulp magazines.

Contrary to Osteen’s interpretation of No Man of Her Own, “They Call Me Patrice” would neither have been a “critical analysis of marriage” nor a “warning about the dream of social mobility.” To pass muster with the editors of Today’s Woman, and to appeal to the magazine’s female readership, the story would have been affirmative about issues such as marriage, family, social mobility, and the American Dream. And, in fact, these issues in “They Call Me Patrice,” like No Man of Her Own, are dealt with positively. Reliance on the handling of these issues in I Married a Dead Man to explain No Man of Her Own cannot possibly be successful, given the existence of “They Call Me Patrice.” Osteen’s failure to discuss the complete literary history of the film wrecks his analysis of the film.

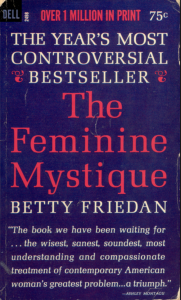

The readership for magazines like Today’s Woman were young females anticipating marriage or already wives. Between 1946 and 1947, the slogan on the cover of Today’s Woman changed from “Dedicated to the Young Homemaker” to “The Magazine for Young Wives.” Today’s Woman was the kind of women’s magazine that Betty Friedan excoriates in chapter two (“The Happy Housewife Heroine”) of The Feminine Mystique (W.W. Norton and Company, 1963). Friedan analyzes fiction published in four women’s magazines: Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, and Women’s Home Companion.

A summary of chapter two, posted on Wikipedia, says, “Friedan shows that the editorial decisions concerning women’s magazines were being made mostly by men, who insisted on stories and articles that showed women as either happy housewives or unhappy, neurotic careerists, thus creating the ‘feminine mystique’—the idea that women were naturally fulfilled by devoting their lives to being housewives and mothers. Friedan notes that this is in contrast to the 1930s, at which time women’s magazines often featured confident and independent heroines, many of whom were involved in careers.”

A summary of chapter two, posted on Wikipedia, says, “Friedan shows that the editorial decisions concerning women’s magazines were being made mostly by men, who insisted on stories and articles that showed women as either happy housewives or unhappy, neurotic careerists, thus creating the ‘feminine mystique’—the idea that women were naturally fulfilled by devoting their lives to being housewives and mothers. Friedan notes that this is in contrast to the 1930s, at which time women’s magazines often featured confident and independent heroines, many of whom were involved in careers.”

(For an alternative analysis of popular magazines, focusing on the non-fiction they published, see “Beyond the Feminine Mystique: A Reassessment of Postwar Mass Culture, 1946-1958,” by Joanne Meyerowitz, in The Journal of American History, Vol. 79, No. 4, Mar., 1993, 1455-1482.)

“They Call Me Patrice” is susceptible to Friedan’s critique of postwar fiction in women’s magazines. Because the conclusion of the novella resembles that of the film, the legitimacy of Friedan’s criticism contradicts Osteen’s interpretation of the film. That is, Osteen’s analysis of the film can’t survive his failure to account for the conclusion of No Man of Her Own being derived from “They Call Me Patrice.”

I am not alone in believing that the screenwriters didn’t use the novel’s ending in their screenplay because they took into consideration the film’s audience. In his review of the film, Geoff Meyer writes:

“No Man of Her Own remains faithful to Woolrich’s novel up to the final minutes when it bypasses the nihilism of Woolrich’s ending as screenwriters Sally Benson and Catherine Turney borrow the conclusion from Woolrich’s novella, They Call Me Patrice (published in 1946 in the woman’s magazine Today’s Woman). Although it weakens the film, the change is understandable in terms of the film’s target audience which was the same as the readership for Today’s Woman.” (Cinémathèque Annotations on Film, Issue 37.)

According to Osteen, Sally Benson’s first draft of the screenplay lacked Helen’s voice-over at the start of the film. Catherine Turney added the voice-over and created the flashback structure of the plot. Osteen says, “[T]his structure more effectively highlights the story’s central deception and its legal and moral implications. Those implications seem straightforward: impersonating Patrice is fraud.” (61)

What Osteen doesn’t recognize is that the voice-over reinforces the significance of Helen’s role in the film. That is, it further contributes to a vital aspect of the film: female agency.

I have elsewhere addressed women’s voice-over in film noir as a challenge to “the longstanding view of film noir,” which I refer to on this website as “the film noir hardboiled paradigm.” The following paragraph is in my commentary from the page Moss Rose, which was originally published in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia (Overlook Duckworth, 2010, 193-194).

“The longstanding view of film noir as having a male subject, with the female relegated to being an object (obstacle or enigma) in relation to the male, is unlikely to remain dominant. New perspectives about women in film noir will have to emerge, if for no other reason than to assess leading female characters in movies that are now acknowledged as film noirs but once were defined as not film noir. For example, film noir has been contrasted with “female gothic” (and related but not identical terms like “period film” and “gaslight melodrama”). The prime reason female gothic has been called different from film noir is its focus on a woman instead of a man. Moss Rose suggests one way the inclusion of women’s film noirs (whether set in the gas-lit past or the atomic present) should lead to changes in the traditional description of film noir. From the start and throughout the film until the end, Rose narrates her story. Although the voice-over may generally be male, Moss Rose shows film noir doesn’t preclude, due to any inherent conventions, female control of the story.”

In his explanation about who killed Steve and why, Osteen says, “In the finished film it is ultimately proven that Steve was killed by gamblers over a debt, which gets Mother Harkness off the hook. The real killer is never revealed in the novel, but Bill and ‘Patrice’ allow the gamblers to take the rap anyway. In other words, the film erases the lovers’ secret, which in the novel remains a permanent blot on their union.” (64)

What Osteen describes isn’t what occurs in the film; it is what happens in the novel!

The following is what actually takes place “in the finished film.” A detective comes to the Harkness house to question Helen. She confesses to killing Steve because she doesn’t want Bill to show the detective a letter in which Mrs. Harkness confessed to the murder just before she died. The detective asks Helen what kind of gun she used. She says it was a .38. He says a bullet from a .38 was found in Steve’s mattress. However, he adds that Steve was murdered with a .32 pistol, which was fired by a “shil,” not a gambler. Furthermore, the murderer is outside the house in the backseat of a squad car. The killer is Steve’s ex-girlfriend, who at the start of the film warns Steve, “Don’t ever brush me off like that.” When the detective returns to the squad car, he says that Steve “must have made a lot of people want to kill him.” His ex-girlfriend replies, “He was a skunk.” The cop sitting beside her quips, “You oughta know, lady, you killed him.”

Steve’s killer in “They Call Me Patrice” is the same kind of person as in No Man of Her Own, an ex-girlfriend. However, in the novella the woman is not introduced until the very end, and her character is dealt with as follows. (Today’s Woman, April 1946, 146)

“[Helen] shuddered, ‘But Bill — What will happen?'”

“Nothing. It’s over already. They’ve already found her….”

“Her?” she whispered.

“Some poor thing who had the misfortune to love him too deeply for her own good. They always do, that kind of guy. Don’t ask me why. She must have followed him here, and not understood what he was up to. She never even gave him a chance to explain.”

The scriptwriters fleshed out the character, the Blonde, so that she is shown at the beginning of the film (when she warns Steve not to dump her the way he has dumped Helen), in the middle (when she orders a gold cigarette lighter) and at the end (when she is in the squad car). The Blonde doesn’t have much of a role in the film; she doesn’t even have a name. Nonetheless, Benson and Turney changed the novella’s solution of the mystery — who murdered Steve — from something out-of-the-blue to a sensible, even predictable, outcome. Thus, the female scenarists not only altered the novel’s conclusion, they also revised how Woolrich dealt with the female murderer in the novella so as to strengthen her character.

Osteen recounts the history of Mrs. Harkness’s letter of confession: how in the novel (but not the screenplay) there is a second letter retracting the first one, and how lines were added and then deleted in different versions of the script. Osteen concludes:

“These gestures do little to mitigate the ending’s implausibilities, but they do demonstrate the slippery moral question at issue: sweet Mother Harkness, symbol of loyalty and devotion, is either a liar or a or murderer or both, and her ‘help’ would contaminate her son’s marriage and grandson’s future life. The problem, however, is not with her but with the institution of marriage, which, both novel and film suggest is founded on deception.” (64)

Osteen inaccurately explains how the letter is made known. He says, “In both novel and finished film a deathbed letter from Mrs. Harkness is uncovered in which she confesses to killing Steve after finding about the forced wedding.” Osteen implies that the discovery of the letter is an accident. In fact, the letter isn’t “uncovered” in the novel or the film.

In the novel, Mrs. Hazzard (Mrs. Harkness in the film) gives the letter to Helen. In the film, Josie, the maid, who is another female pillar of strength in the household, hands it to Helen. Josie explains that Mrs. Harkness wrote the letter three months earlier, the night she died. Earlier that evening, Mrs. Harkness had gotten a phone call from Steve and, before being disconnected, she overheard him threaten Helen. She and Bill traced where the call had come from (the home of a justice of the peace), and Bill drove off to find Helen. Later, Mrs. Harkness saw Helen leave their house in taxi. Then she discovered Helen had taken a pistol and bullets from a desk drawer. She grasped what Helen meant to do. Before dying, Mrs. Harkness wrote a letter in which she took responsibility for murdering Steve, and she instructed Josie to give the letter to Helen only if the police came to the house to investigate Steve’s death.

When Helen tells Bill about the letter, he wants to show it to the police. But Helen refuses. She doesn’t want a blot on Mrs. Harkness’s reputation because she thinks that Bill’s mother was also like her own mother. A key aspect of No Man of Her Own, ignored by Osteen, is the prominent role of women as agents of action in the film. Every person associated with blame for Steve’s death is a woman, and deliberately so. Helen, to keep Mrs. Harkness’s confession a secret, tells the detective that she killed Steve. Mrs. Harkness was willing to take responsibility for the murder to ensure that no criminal charges could be brought that might break up the family of Helen, the child and Bill. Of course, the woman who actually slays Steve is his ex-girlfriend.

All three women share a related motive: Steve has threatened their “family.” The ex-girlfriend kills him because he dumped her, ending their romantic relationship. Mrs. Harkness says in her letter, “For those who doubt my ability to carry out this deed, I can only answer that one calls upon great resources of strength when the happiness of those that one loves is in jeopardy.” Helen’s reason for killing Steve is the same as Mrs. Harkness’s. Helen realizes during the wedding ceremony that, unless Steve dies, he will demand more and more and, eventually, he could destroy the Harkness family.

Contrary to what Osteen believes, “the problem” that relates to Mrs. Harkness’s letter is not “the institution of marriage,” but the security of family. In fact, Helen’s voice-over at the conclusion of the film does not pertain to romance with Bill, much less marriage. She says, “The house we live in is so beautiful.” The house stands for family. Helen is willing to be arrested to preserve the sanctity of the memory of the family’s matriarch, “Mother” Harkness. Mrs. Harkness was willing to have her reputation ruined in order to protect Bill, Helen and Helen’s son.

These are strong women. The night that Bill almost tells his father about his encounter with Helen downtown, Mrs. Harkness says that soon Helen will be running the house herself. That is, she is going to be the new family matriarch. No Man of Her Own is a women’s film as well as a film noir. When Steve comes to Caulfield and jeopardizes the security of the Harkness’s, the present and future matriarchs each take action to save their family. Both women are willing to take responsibility for the murder of the man who threatens their family.

The issues of social mobility and the American Dream are present in the film. However, the third issue isn’t marriage, it is family.

Furthermore, because Osteen inaccurately explains the identity of Steve’s killer and the motive for his murder, his contention that the “hastily wrapped-up happy ending” doesn’t actually alter the film’s “critical analysis of marriage” is untenable.

Osteen analyzes No Man of Her Own via the film noir hardboiled paradigm. The film’s merits, he finds, lie in its darkness, its negative views about marriage, social mobility and the American Dream. As I have shown, he makes a very poor case. His evidence is unsatisfactory, he leaves out information that would contradict him, and he frequently misrepresents what actually occurs in the film.

Addendum II: No Man of Her Own as both Romantic Melodrama and Film Noir

As noted above, in my commentary about No Man of Her Own in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia (Overlook Duckworth, 2010, pp. 212-213), I emphasized that the film should be understood as representing – in its plot as well as its visual style – both romantic melodrama and film noir.

Ed Gorman, the well-known crime writer, shares my view. In 2012, Centipede Press issued a new edition of I Married a Dead Man. In his introduction to the novel, Gorman says:

Ed Gorman, the well-known crime writer, shares my view. In 2012, Centipede Press issued a new edition of I Married a Dead Man. In his introduction to the novel, Gorman says:

“To me there are two ways to look at I Married a Dead Man. The first is that it is the finest soap opera ever written. This is not trying to demean it in any way. I’m talking about the genre it resembles, the form and where it could comfortably fit into the strictures of popular fiction…The second way to assess I Married a Dead Man is as the ultimate noir.” (10)

Curiously, Thomas C. Renzi, in his otherwise well-researched book, Cornell Woolrich from Pulp Noir to Film Noir (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006) only references the novel I Married a Dead Man. He has no mention of “They Call Me Patrice.” This may be the reason why he considers the conclusion of No Man of Her Own as akin to a Hollywood sellout of Woolrich’s dark vision.

Unlike Mark Osteen, Renzi sees melodrama as well as noir in the film. However, in contrast to myself, as well as Ed Gorman, Renzi prefers to associate Woolrich with the noir and to relegate the association of the melodrama with the director, Michael Leisen. He says:

“This is Woolrich’s story, totally noir in the bleakness of its outcome, in how it truncates hopes and happiness, in its finale of despair and damnation. But this is not Leisen’s story. For the most part, Leisen’s film, the first of several adaptations of I Married a Dead Man, is extraordinarily tenacious in adhering to the Woolrich story line. Yet in inimitable Hollywood style, it reverses the novel’s final collapse into utter despair and caters to popular demand for the happy ending. Despite this, and despite its presenting itself as a woman’s ‘weepy’ – the sort of melodrama Leisen was noted for and which could very fittingly serve as a classification for this particular Woolrich novel – the film faithfully renders much of Woolrich’s noir-ish mood and intent throughout most of the telling.” (329)

“This is Woolrich’s story, totally noir in the bleakness of its outcome, in how it truncates hopes and happiness, in its finale of despair and damnation. But this is not Leisen’s story. For the most part, Leisen’s film, the first of several adaptations of I Married a Dead Man, is extraordinarily tenacious in adhering to the Woolrich story line. Yet in inimitable Hollywood style, it reverses the novel’s final collapse into utter despair and caters to popular demand for the happy ending. Despite this, and despite its presenting itself as a woman’s ‘weepy’ – the sort of melodrama Leisen was noted for and which could very fittingly serve as a classification for this particular Woolrich novel – the film faithfully renders much of Woolrich’s noir-ish mood and intent throughout most of the telling.” (329)

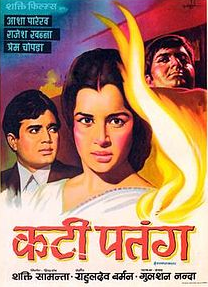

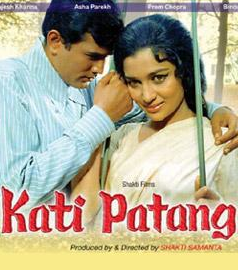

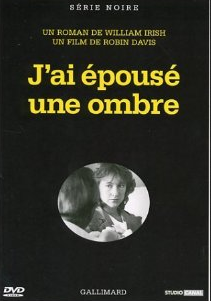

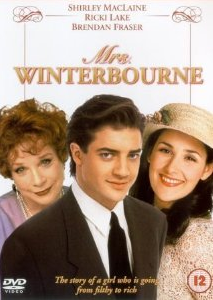

After his analysis of No Man of Her Own, Renzi discusses three other film interpretations of I Married a Dead Man: J’ai épousé une ombre (1983, France), Mrs. Winterbourne (1996, United States), and She’s No Angel (television, 2002, United States). There are at least four additional film versions that Renzi omits: Shisha to no kekkon (1960, Japan), A Intrusa (television, 1962, Brazil), Kati Patang (1970, India), and Nenjil Oru Mull (1981, India), which is the Tamil remake of Kati Patang.

Although the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) website does not cite Cornell Woolrich’s work as the literary source for Kati Patang, Wikipedia correctly makes the reference. Kati Patan translates from Hindi as “Cut Kite,” as in a kite’s cut (severed) string, causing the kite to float off. It was box office hit, and Asha Parekh, who plays the “Helen/Patrice” character, won the 1970 Best Actress Award given by Filmfare for Hindi films. There are many different DVD’s available of this Bollywood version of I Married a Dead Man. Some are only in Hindi, others with subtitles. For example, my DVD offers subtitles in eight (!) languages: English, French, German, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, Portuguese, and Swedish.

Gratitude

Unfortunately, Cornell Woolrich’s “They Call Me Patrice” has never been reprinted.

I am very grateful, therefore, to Francis M. Nevins for providing me with a xerox of the novella as it was originally published in the April 1946 issue of Today’s Woman magazine.

I am very grateful, therefore, to Francis M. Nevins for providing me with a xerox of the novella as it was originally published in the April 1946 issue of Today’s Woman magazine.

Mr. Nevins, Professor Emeritus at the Saint Louis University School of Law, has been awarded two Edgars by the Mystery Writers of America for Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988) and Royal Bloodline: Ellery Queen, Author and Detective (Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1974). He has edited the following five anthologies of short stories by Woolrich: Nightwebs (Harper & Row, 1971), Darkness at Dawn (Southern Illinois University Press, 1985), Night & Fear (Carroll & Graf, 2004), Tonight, Somewhere in New York (Carroll & Graf, 2005), and Love and Night (Perfect Crime Books, 2011). Mr. Nevins is also a prolific author of crime short stories and novels.