Quiet Please, Murder

Introduction

It is bewildering that Quiet Please, Murder is only listed in the filmography of Andrew Spicer’s Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (The Scarecrow Press, 2010). It was released in 1942, over a year after The Maltese Falcon, which some consider one of the earliest film noirs (along with Stranger on the Third Floor and The Letter, both from 1940). Moreover, if, as I believe, film noir (in both crime films as well as spy films) is underway by the late 1930s in the UK as well as the US, then Quiet Please, Murder was released several years after the advent of film noir. (For my history of spy noirs in the UK and the US dating from the mid-late 1930s, see the UK and US filmographies associated with the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.)

There are murders throughout the film, as well as attempted killings. Slayings are quiet: either by a knife or a pistol with a silencer. In addition to the darkness in the scenes with gunfire, the muffled sound of the shots increases the film’s oneiric atmosphere. There is a femme fatale dressed in black and a private eye in a trench coat. The plot is complicated. Anticipating postwar film noirs, characters speak to each other on the subject of psychoanalysis. And, crucially, in scene after scene there is an excellent noir visual style.

Quiet Please, Murder has many aspects of a crime noir, but it isn’t at all hardboiled. Therefore, despite the prominence of a femme fatale and a private eye, the script undermines rather than substantiates the film noir hardboiled paradigm. For example, instead of the screenplay representing the influence of hardboiled crime fiction, its author, John Larkin, had writing credits for other non-hardboiled detectives, Charlie Chan (five) and the Lone Wolf (one).

The film lacks any key characters in the spy noirs of the Second World War era. There are no spies, fifth columnists or resistance fighters. (For more about these characters, as well as the relationship of spy noirs to film noir, see the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.) Nonetheless, Quiet Please, Murder is included in Paul Mavis’s The Espionage Filmography: United States Releases, 1898 through 1999 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001, 254). Consequently, I have listed it on the page Spy Noirs, US, from Dan Hodges.

Quiet Please, Murder hasn’t been acknowledged as an early film noir, much less one that is outstanding. Its femme fatale has been overlooked as one of film noir’s most treacherous. Following Humphrey Bogart’s Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon and Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes in The Voice of Terror, Richard Denning’s Hal McByrne is film noir’s third private detective. (For a critique of the private eye in film noir, see the page The Missing PI in Film Noir.)

Given the film’s unfamiliarity, I provide below a detailed recounting of the plot, including the dialog from several scenes.

Finally, in the Addendum I discuss the social message in Quiet Please, Murder, which is unique among film noirs released during WWII.

Main Credits

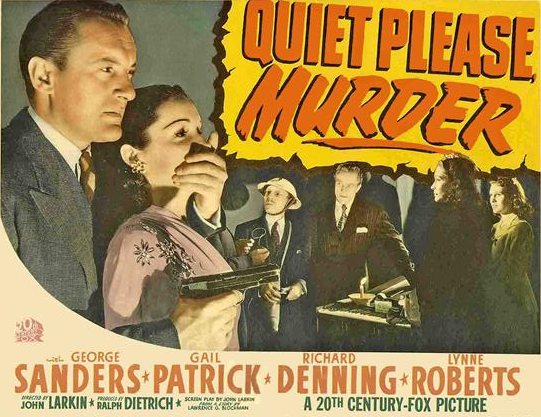

Director: John Larkin. Screenplay: John Larkin. Producer: Ralph Dietrich. Cinematographer: Joseph MacDonald. Music: Emil Newman. Art Director: Richard Day, Joseph C. Wright. Editor: Louis R. Loeffler. Cast: George Sanders (Jim Fleg, also “Lt. Craven”), Gail Patrick (Myra Blandy), Richard Denning (Hal McByrne), Lynne Roberts (Kay Ryan), Sidney Blackmer (Martin Cleaver), Kurt Katch (Eric Pahsen), Margaret Brayton (Miss Oval), Charles Tannen (Hollis), George Walcott (Benson, uncredited). Released: Twentieth Century Fox, December 21, 1942. 70 minutes.

Presentation

The following introductions to the main characters set up the plot.

Jim Fleg/”Lt. Craven”:

In the opening scene Fleg murders a guard at a city’s public library in order to steal the “Richard Burbage edition of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.” Fleg makes forgeries of the book for sale to people throughout the US who are willing to pay large sums for what they believe is the original “Burbage Hamlet.” (Such an edition never existed, but Burbage, who is considered to be England’s first great stage actor, was the star of Shakespeare’s theater company, and he played the title role in the first performances of many of the Bard’s plays, such as Hamlet, Othello and King Lear. For more about the esteem in which Burbage was held by his contemporaries, see the Postscript below.)

Later in the film, posing as “Lt. Craven,” Fleg stages an elaborate hoax, with many confederates pretending to be police officers, to steal several other valuable rare books from the same library.

Myra Blandy:

Ostensibly an expert on rare books, Myra also procures buyers for Fleg’s forgeries. Against Fleg’s instructions, she sells a copy to Martin Cleaver. Although Gail Patrick has not been appreciated for her performance in Quiet Please, Murder – after all, the film has been ignored by film noir historians – her femme fatale character is one of film noir’s most ruthless and evil. (Fleg calls her “Lady Dracula.”)

Martin Cleaver:

Fleg tells Myra that Cleaver is “buying for Goering or Himmler, investing in works of art. Literary rarities, like diamonds, are supposed to be safe in the event of postwar inflation…[He] is a sadist. There’s not an ounce of mercy in him.” Cleaver purchases a fake Hamlet after Myra tells him it is authentic. (He spends $20,000, but the ever-unscrupulous Myra, when she gives Fleg $5,000, says Cleaver only paid $7,500.) When Cleaver learns he has been swindled, he demands Myra set up a meeting for him and Fleg within an hour. Cleaver is accompanied by two assassins, Pahsen and Benson. (Pahsen shoots the bookseller who was in cahoots with Myra and Fleg.)

Hal McByrne:

A private detective, McByrne confronts Myra at her office on behalf of someone else who bought one of Fleg’s forgeries. In return for shielding her from any publicity that would harm (if not end) her business, he asks for Myra’s help to build a case against Fleg. Myra writes a check as a retainer. But she is more to McByrne than a client; he is immediately infatuated with her. After he asks her out to dinner, he says, “Every instinct tells me I’m a fool, but I’m trusting you because I want to.”

As soon as McByrne leaves Myra, she phones Cleaver and asks him to leave a book in her name at the information desk at a public library (where Fleg stole the Hamlet). She says, “I’ll have Fleg pick it up. That’ll identify him when he asks for it. Oh, by the way he uses the name McBryne. Hal McBryne. He mustn’t know about me.”

Next, Myra visits Fleg and tells him that after her dinner date, McByrne has “an appointment at the public library.” Fleg decides to kill “two birds with one stone.” Not only will he take care of McByrne, he will also rob the library of some more rare books.

After their dinner, Myra allows McByrne to romance her a little during a cab ride. He says her eyes “mean trouble,” but he likes trouble. He puts his arm around her head and tries to kiss her. Before he can, she complains, “Be careful. That’s a new hat.” He says, “What a crack to make at a time like this.” (McByrne will bring up the hat incident close to the end of the film.) When the taxi reaches the public library, she asks him to go in and get a book at the information desk that is on hold in her name.

Before McByrne can ask the librarian, Kay Ryan, for Myra’s book, Flag himself butts in and loudly identifies himself to Kay as “Lieutenant Craven, homicide squad.” Fleg heads off “to get a good murder mystery, plenty of blood,” which is an apt description of Quiet Please, Murder.

Cleaver is already waiting near the information desk. Based on the lie Myra told him, when Cleaver hears McByrne give his name to Kay, he thinks the man is Fleg. Cleaver, addressing McByrne as “Fleg,” takes McByrne to one of the library’s rooms to have a talk “about certain literary forgeries.” Unseen, Myra enters the library.

Each of the three men (Cleaver, McByrne and Fleg) has never seen the other two before. And only Myra knows that they are all in the library at this time.

Cleaver insists on calling McByrne “Fleg” and having McByrne repay the money Cleaver spent on the fake Hamlet. McByrne, of course, denies that he is Fleg. Acting on Fleg’s plan to murder McByrne, Fleg’s “bodyguard,” Hollis, comes up to Cleaver and McByrne and says that he has a note for “McBryne.” Since Cleaver refuses to believe that McByrne is McBryne, he takes the piece of paper, reads it and goes off with Hollis, leaving McByrne behind with Benson, one of Cleaver’s two assassins.

As Cleaver walks by Pahsen, his other assassin, Cleaver hands him the note. It says, “Must see you at once. Reading room balcony. Myra.” Given Fleg’s forgery skills, the handwriting looks feminine. The note is meant to draw McByrne to an isolated location, where Hollis will kill him. Instead, Hollis stabs Cleaver. Before he dies, he staggers to a railing and tumbles over it onto a lower level. Several people witness his fall, including Pahsen, who, because of the message, assumes Myra is responsible for his boss’s murder.

McByrne, who has slugged and gotten away from Benson, comes upon Cleaver’s corpse just before Fleg, who is known at this time to McByrne as Lt. Craven.

Fleg orders the library to be locked up. He is surprised when McByrne introduces himself, having thought the detective would be the dead man. Then he is stunned when McByrne tells him the murder victim is Cleaver, since Sanders had no idea Cleaver would be in the library.

Myra realizes she should get out of the building, but it is too late for anyone to leave. When Fleg sees her, he knows it was she who arranged for both Cleaver and McByrne to be there. He warns her against making even one careless move. She responds, “I never make any.”

Fleg tells Hollis, “Nail McByrne first chance you get. He’s still with us.”

McByrne also sees Myra. Their exchange is the quintessence of one between a femme fatale and her dupe.

He says to her, “Some nut [i.e., Cleaver] mistook me for Fleg. Was he going to be here tonight?

She replies, “I wouldn’t know. Don’t you believe me?”

“Sure, beautiful. Why shouldn’t I?”

“You didn’t tell the police I know Fleg?”

“Just keep your mouth shut and let me handle this. You hired me and you’re going to get service. You ever have a funny feeling you walked right into something? Mine says there’s a bullet looking for me. Keep your eyes open. I need a pal.

Myra warmly smiles at McByrne as he leaves her.

Fleg executes his plan to steal five valuable rare books. However, McByrne has become suspicious about Fleg being a real police officer. When Fleg isn’t looking, McByrne picks up the books and puts them on a book cart. Myra sees what McByrne has done, removes the books from the cart and hides them in the stacks.

McByrne’s real “pal” is the librarian, Kay.

He tells her he has a hunch. “[W]hat’s going on now [i.e., Fleg’s interest in the rare books] is tied up with that Hamlet job.”

She asks, “You think whoever killed that guard….”

“Is in the building again? Maybe.”

After he placed the rare books on a cart, McByrne knows a library worker moved the cart somewhere into the stacks, based on the code number for the cart. He asks Kay to show him where the cart was supposed to go. As they walk among the bookshelves, she explains the Dewey decimal system to him. (This casual conversation later enables McByrne to figure out where Myra hid the books.)

He tries flirting with her, “You ever try using that concentration on something that wears pants and smokes a cigar.”

Kay is cordial, but firm, “Uh-huh. We’re getting married when the army’s through with him.”

“You know I wish I’d met you before noon today.”

“Why?”

“I wouldn’t have fallen for somebody else [i.e., Myra].”

“You couldn’t compete with my army man.”

When they locate the cart, the rare books are missing. Myra, hidden in shadows, has been watching McByrne and Kay. After Kay returns to work, Myra steps out of the stacks. She tells McByrne more lies.

“[I’ve been] looking for you, darling. I have to tell you something. Craven, he’s Fleg…I was afraid to tell you before, but I want to play square with you…Don’t let on you know. Now’s your chance to get him. Mac, you do believe me?”

“Oh, I want to beautiful.” McByrne takes Myra in his arms.

Myra goes off, and Hollis, saying that he is Craven, calls down to McByrne from an upper floor in the stacks. When McByrne reaches the top of the stairs, Hollis slugs him. Hollis is about to stab McByrne when Fleg, shrouded in darkness, orders him not to because he thinks McByrne knows where the rare books are. Before Fleg leaves, he tells Hollis to wake McByrne up and then work him over until he says what he did with the books.

Elsewhere in the library one of Cleaver’s assassins, Benson, tells the other, Pahsen, to find Myra and kill her. Pahsen shows Benson a small, thin rope with a noose – which he can use to strangle Myra.

McByrne gets the upper hand on Hollis, breaks free from him and runs off into the stacks. He makes it into a room, locks the door and discovers Pahsen is there. Getting the upper hand of Pahsen, McByrne searches through Pahsen’s wallet, where he finds the note signed “Myra.” Since Pahsen is a mute, McByrne can’t question him. As the two men leave the room, the camera shows Pahsen’s noose lying on the floor.

In another room McByrne comes upon Myra. Now he has a different view of her.

He says, “I figure it like this. After Cleaver put the screws on, you ran into me. I was yelling Hamlet, too. Cleaver used a gun, I used a jailhouse [i.e., before McByrne accepted a retainer from Myra, he had threatened to go to the District Attorney with what he knew about her involvement in selling Fleg’s forgeries]. You were on a spot.”

“I know what you’re thinking, Mac, and you’re wrong.”

“Am I? You played me off against Cleaver. You told him the guy who’d come to pick up a book would be Fleg. You knew he’d have his way or kill. [Myra shakes her head and says, “No.”] Somewhere along the line you also told Fleg that I was Mr. Trouble. He said he’d take care of me, right?”

“Mac, you’re so wrong.”

“Beautiful, you wouldn’t be you if you weren’t lying. You knew I’d walk in here tonight with two men laying for me. Fleg sent a note, using your name, to get me up on that balcony. [McByrne hands Myra the note he took from Pahsen’s wallet.] He needed a body to stage a fake police investigation. And I was elected. And you knew it. [Myra again denies it.] Anyway, Cleaver went instead and got stuck with Hollis’s knife. And all the time you were my pal!”

After a little sweet talk, Myra says, “You won’t believe that, but it’s true.”

“I can try.” And they kiss. Then McByrne says, “You kind of took a shot at me before. I had no hard feelings. Because you’re what I like.”

“You can trust me.”

“Well, I don’t expect you to play straight. I just want you to be around and in the clear when this is all over. We can have some fun.”

Her handbag falls on the floor, and its contents spill out. McByrne picks the stuff up, and he sees a note, “See 31 – 9:30.” Patrick says it is a reminder of an appointment she has at 9:30 the following morning at a bookstore on 31st Street.

Kay rushes into the room to tell McByrne that she has realized, “Those policemen, they’re fakes. I heard them talking. They stole the books.”

McByrne, as he is about to climb out a window to leave the library and get help, says, “Myra, keep an eye on the kid. There’s a guy in the army writing letters to her. Gotta do our bit.”

Kay walks off, and Fleg comes up to Myra. He asks her where McByrne is, and she lies that she doesn’t know.

He says, “You have fallen for him.”

“Don’t be silly. I delivered him to you, didn’t I?”

They see McByrne being brought back into the library. (His escape to get help failed.)

Fleg asks Myra, “Does he know about me?” She nods to confirm.

“And that little librarian, maybe she knows, too.” She nods her head again.

“That all I want to know.”

Fleg sends Kay into the stacks for a book.

He says to his assassin, “Hollis, the girl [i.e., kill her].”

McByrne protests, “Let her alone, Fleg. Call that man off. That girl can’t hurt you.”

“No, but she can spoil my set-up since she knows things that you know.”

At that moment there is an air raid drill. Everyone in the library goes to the shelter in the basement, and the building’s lights are turned off to comply with a citywide blackout. As Fleg and his men head toward the shelter in the darkness, McByrne slugs one of the phony cops, grabs his pistol and gets away.

The following scene, in terms of its noir visual style and dramatic intensity, is one of the finest in the early years of film noir.

Kay hears Hollis’s footsteps and senses she is in great danger. In the darkness of the stacks, she runs, taking off her shoes to move as silently as possible. She goes up a stairway to the next level and continues her flight. When she reaches the end of the last aisle, she finds both of the doors to other rooms are locked. Hollis closes in, not with a knife but a gun. She sees him and, as he steps up to her, she screams and faints.

McByrne hears Kay’s scream and calls to her. Leaving Kay, Hollis double backs toward McByrne. When Hollis sees McByrne’s flashlight on the stairway, he fires. McByrne falls to the floor at bottom of the stairs. His flashlight is still on and is pointed up at Hollis as he descends a couple of steps. Suddenly McByrne opens his eyes and shoots Hollis dead.

McByrne finds Kay unconscious, revives her and shoots at one of the locked doors in order to open it. Fleg hears the shot, and he catches up with them. Myra has come with Fleg, but he tells her to stand next to them because, like Kay, she knows too much. In the darkness of the room, to indicate what will happen if McByrne doesn’t turn over the rare books, Fleg has some candlelight shine on Benson’s corpse, lying nearby on the floor.

But McByrne is quite clever. He tricks Fleg into letting him to make an inter-office phone call. The library’s air raid warden answers the phone, and he hears McByrne say, “All clear.” Fleg thinks this is the signal for someone to bring McByrne the rare books. Instead, the message is interpreted that the air raid drill is over, so all the lights in the building are turned on. However, since the blackout is actually still in effect, real police rush into the library to have the lights shut back off. That gives McByrne the opportunity to tell them to arrest Fleg and everyone in his gang.

The police search Fleg’s apartment, find the original Burbage Hamlet and return it to the library. It is 3:00 AM, just over six hours since McByrne came into the library.

One by one the police release everyone. Because the cops have no reason to be suspicious of Pahsen, he is sent outside, too.

In a room with books cataloged in the 900s, McByrne tells Myra that he kept her association with Fleg a secret from the police.

He says, “When I protect a client, I protect him. You’re in the clear.” She steps forward to kiss him, but he backs way. She senses his abrupt coldness.

“Something’s wrong. What is it?”

“Where are those five books you lifted off that stack wagon?” (She doesn’t answer.) “Don’t give me that. You’ve got ‘em and you let Fleg gun for me thinking I had ‘em.”

“You’re out of your mind.”

“Stop acting. You tried to play me off against Fleg. And why not? I was a lucky guy. I might knock off Fleg. That’d make you top man in the racket. A swell set-up. And you’re made of ice.” He tears up her check that was his retainer. (Now she is no longer his client.) “I kept my end of the bargain [i.e., keeping her in the clear]. You’re not in the Fleg case so far, but from right now you’re on your own.”

“You’ve got to listen to me.”

“Where are those books?”

“I don’t know.”

He reaches into her pocketbook and removes the paper with her handwriting, “See 31 – 9:30.” He searches the stacks until he finds the five books on the shelf at C31-930.

“You sure had a date in the morning, with 150 grand.”

“You going to blame a girl for trying? I’d have told you.”

“In a pig’s eye. Look beautiful, nothing ties you to the killings tonight – no proof – but I’m going to nail you for the Hamlet forgery.”

“Revenge?”

“No. To teach you a lesson. You had me going for a while, but a man doesn’t mean a thing to you. You live for little Myra and nobody else. And you’ll always be that way.”

“Mac, what you said was true until you came along.”

“Don’t hand me that. Any dame who worries about her hat in a taxi. That was the tip-off to me, but I didn’t want to believe it.”

“Mac, I love you. It’s the first time I’ve been able to say it to any man.”

“Ah, lay off. You’ve yelled ‘wolf’ too many times. I wanted to give you a break, but you tried to destroy Kay, that innocent kid. You were the only one who knew she’d spotted Fleg, and you tried to tip him off about her.”

“I couldn’t help it. I was jealous.”

“You? No. You wanted to convince Fleg you were on his side, and that was your big mistake, sister.”

“You were falling for her.”

“No, she doesn’t mean a thing to me, only what she stands for. She’s waiting for some guy in the army. But you wouldn’t get it. There are thousands like Kay, and a lot of guys in the army counting on them, daydreaming about things after the war. Her useless death would have hurt him. Ah, maybe I’m a sentimental slob, but I don’t buy that [i.e., that Myra is in love with him]. Thanks for the buggy ride.”

Holding the five books, McByrne leaves Myra behind in the room and steps into the lobby. Immediately, a plainclothes policeman comes up, takes the books and says that McByrne must have known all along where they were. Still keeping Myra in the clear, McByrne gives the policeman Myra’s memo with the shelf location and says, “I found this on Fleg and figured it out all by myself.”

The policeman goes off, and Myra enters the lobby. She begs McByrne to see her home. He refuses. She says, “Cleaver’s men are out there, and they know what happened [i.e., that she sold Cleaver a fake Hamlet]. They’ll kill me.”

McByrne replies, “Maybe they will, maybe they won’t. People who do business with Hitler’s mob know the payoff. Go ask the cops to take you home.”

“Oh, Mac, don’t desert me now.”

“I’m sick of your lying.”

“I’m not lying. I tell you I’m terrified.”

McByrne goes into another room. As in the scene in the stacks when Hollis hunts Kay, the following episode has outstanding noir visual style.

Myra walks through the dark, empty lobby to the front door. She steps outside. It is still night, and the streets are deserted. As though it is within her mind, we hear a voice-over from Cleaver that repeats his warning to her earlier in the film, “I do not work alone.” Moments later there is a voice-over from Fleg of his own previous warning, “My dear, we all set in motion the means of our own destruction.”

A cop tells her a taxi stand is four blocks away. She starts walking. Pahsen emerges from shadows near the library entrance. The cop ignores Pahsen when he goes in the same direction as Myra. At first she is unaware Pahsen is closing in. Hearing his footsteps, she looks back and sees him. She walks faster.

There is a cut to the front of the library. Two plainclothes policemen ask the cop which way Pahsen went because they have just discovered he was one of Cleaver’s gunmen. They drive off in a patrol car to find him. There is a cut to Pahsen, who is standing up in a pitch-black alley and putting a knife in a pocket of his overcoat. As he comes out of the alley, the police spot him. After they grab him, they see Myra’s corpse.

The ending of the film is bittersweet.

Before McByrne leaves the building, Kay approaches him with a big smile.

“Hello,” she says. “Can you tell me all about it now? I’ll buy you a cup of coffee.”

He replies sharply, “And put poison in it?” She looks down, crestfallen. He realizes his error. “I’m sorry. I guess you’re not all alike [i.e., all women], but right now I’m not very good company.”

When McByrne steps away from her, he notices one of Myra’s gloves on the floor. He picks it up. Kay says, “She was involved somehow, wasn’t she? You liked her, too.”

McByrne comes back to Kay. Comparing Myra to a lost cat, he says that, although he could have done without her, he had to have her.

He pockets the glove and says, “Come on. I’ll buy the coffee.” He turns around and walks to the front door, and she comes up next to him and takes his arm. They leave the library together.

Addendum

There are several other scenes that are of interest. In three of them Fleg delves into his brand of psychoanalysis that people have a secret desire to be hurt, a subconscious wish for “punishment.” (One is when Myra visits Fleg before her date with McByrne; another is before Fleg shows Hollis’s dead body to McByrne, Myra and Kay; and the last is after Fleg has been arrested and he is staring at his handcuffs.) Also, there are instances in which McByrne, as well as the real police, show how mercenary they are regarding their claims for reward money from the library after the original Burbage Hamlet and the other five rare books are returned.

The ending of Quiet Please, Murder underscores the film’s unique social message. Kay Ryan is not only a single young woman with a job, she also has a fiancé fighting in the war. I’m not aware of any other film noir released during WWII that emphasizes either as strongly or as consistently that men overseas can trust their women at home to remain faithful.

When Kay and McByrne first run into each other in the library, he is going to the information desk to pick up Myra’s book, and she is some distance away coming down a staircase. Mistaking McByrne by his apparent physical resemblance to her boyfriend, Kay calls out to him as “Johnny.” Once she realizes her error, for the rest of the film she maintains a warm but professional demeanor with McByrne.

Both Kay and Myra have jobs, but the ways in which they earn a living are suggestive of the differences in their characters. Myra is a private business owner. Whether appraising and selling legitimate rare books or colluding with Fleg to market his forgeries, her clients are wealthy connoisseurs. The books they purchase from Myra are considered art objects or, as for Cleaver, investments. In other words, these books aren’t to be read for entertainment or education.

Kay, on the other hand, is a public worker. She is one of a large number of employees at a government institution, the city library, where books are borrowed, not bought, and they are read and returned, not collected and hoarded. Myra, working with Fleg, fleeces her elite clients. Fulfilling the mission of a public library, Kay serves people from all walks of life. In fact, there is a connection between Kay and her fiancé, Johnny. As a soldier, he is also on the government payroll. His role is to protect America’s democracy, which is represented in the film by the library. For example, the effort by the library staff to comply with the blackout (e.g., keeping the lights shut off and sending everyone in the building downstairs to a shelter) shows how they – as a stand-in for the American home front in general – successfully carry out wartime responsibilities. In other words, like members of the armed forces, those in the library’s workforce cooperate together; they have one another’s back. Myra and Fleg not only deceive the buyers of fake Hamlets, each of them betrays the other’s life.

Above, I have quoted the scene near the end of the film when McByrne, after he tells Myra he is finished with her, contrasts the always disloyal and dishonest Myra with the ever-loyal and honest Kay. McByrne finds Myra so unwaveringly black-hearted that he ends up tarring Kay (i.e., all women) with the brush of Myra’s poisonous selfishness. When he sees Myra’s glove, he comes to his senses and acknowledges that not all women are bad, even if the one he wanted was.

Because Kay’s interactions with McByrne are mature, not cloying, Quiet Please, Murder admirably conveys its social message that men in combat can rest easy about women’s sexual behavior on the home front. Furthermore, Kay isn’t a goody two-shoes. On the contrary, she is smart and self-reliant. She figures out by herself that Fleg is an impostor and a criminal. Also, she nearly escapes on her own from Hollis when he pursues her to kill her.

It is notable that this wartime film ends with two characters whose lives are so dissimilar: one that is about teamwork and the other about individualism. Kay is twice associated with a group, her coworkers at the library and her fiancé in the army. She is, therefore, a positive character, and it is no surprise that she has moxie and is true to her man. McByrne is doubly linked to a loner, himself (a private eye) and Myra (nobody’s partner, in business or romance). When the film was released in March 1943, individualism was a negative trait. For example, Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine in Casablanca, which was released just two months before, won’t stick his neck out for anybody. He has to undergo conversion to be willing to fight fascism. (For an in-depth analysis of the theme in spy noirs of “converted to the Allied cause,” see section V in Spy Noirs and the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.)

In short, Rick has to shift from McByrne’s individualism to Kay’s teamwork. These distinctions between McByrne and Kay foreshadow what we can imagine will occur after the film is over. Kay will continue to hold Denning’s arm until they find an all-night cafe. They will have some coffee and talk, then go their separate ways. She will be looking forward to her Johnny’s return, and – so noir! – Denning will be looking back on the femme fatale he couldn’t resist falling for and can never forget. Kay has a future with her fiancé, and Denning has nothing and no one.

Postscript

As with the majority of private eye film noirs released from 1941 to 1957 (i.e., 17 of 30), Hal McBryne isn’t a hardboiled detective.

Quiet Please, Murder is another of many examples of the failure of the film noir hardboiled paradigm either to accurately describe the kind of PI most often found in film noirs (i.e., he isn’t hardboiled) or to legitimately relate hardboiled crime fiction with film noir. See the page The Not Hardboiled PI in Film Noir.

Myra Blandry is the client of Hal McBryne. Since she tries to get McBryne murdered, Myra is a “killer client.” See the page The Killer Client & the PI.

In contrast to Hal McByrne, in postwar film noirs with a private eye, the detective frequently doesn’t wind up alone but instead gets a girlfriend. See the page The Sweetheart & the PI.

For more about “conversion” in US spy noirs during the Second World War era, such as Casablanca, see the section “Converted to the Allied Cause” in the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.

A postwar film noir, The Unfaithful (1947), takes a very different view than Quiet Please, Murder about how women at home during WWII behaved sexually while their husbands were abroad in battle. See the page The Unfaithful.

Regarding Richard Burbage, in The New York Review of Books (April 21, 2016), Shakespearian scholar Stephen Greenblatt opens his essay, “How Shakespeare Lives Now,” with the significant contrast in contemporary reactions to the deaths of the Bard himself and his first great interpreter. (Greenblatt is the editor of the The Norton Shakespeare, and his most popular work is Will in the World, a biography of Shakespeare. He won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 2012 and the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2011 for The Swerve: How the World Became Modern.)

“Shakespeare’s death on April 23, 1616, went largely unremarked by all but a few of his immediate contemporaries. There was no global shudder when his mortal remains were laid to rest in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. No one proposed that he be interred in Westminster Abbey near Chaucer or Spenser (where his fellow playwright Francis Beaumont was buried in the same year and where Ben Jonson would be buried some years later). No notice of Shakespeare’s passing was taken in the diplomatic correspondence of the time or in the newsletters that circulated on the Continent; no rush of Latin obsequies lamented the ‘vanishing of his breath,’ as classical elegies would have it; no tributes were paid to his genius by his distinguished European contemporaries. Shakespeare’s passing was an entirely local English event, and even locally it seems scarcely to have been noted.

“The death of the famous actor Richard Burbage in 1619 excited an immediate and far more widespread outburst of grief. England had clearly lost a great man. “He’s gone,” lamented at once an anonymous elegist,

and, with him, what a world are dead,

Which he revived, to be revivèd so

No more: young Hamlet, old Hieronimo,

Kind Lear, the grievèd Moor, and more beside

That lived in him have now for ever died.

“William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, was so stricken by the actor’s death that months later he could not bring himself to go to the playhouse ‘so soon after the loss of my acquaintance Burbage.’ It was this death that was publicly marked by him and by his contemporaries, far more than the vanishing of the scribbler who had penned the words that Burbage had so memorably brought alive.

“The elegy on Burbage suggests that for some and perhaps even most of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, the real ‘life’ of the characters and their plays lay not in the texts but in the performances of those texts. The words on the page were dead letters until they were ‘revived’ by the gifted actor. This belief should hardly surprise us, since it is the way most audiences currently respond to plays and, still more, to film.”