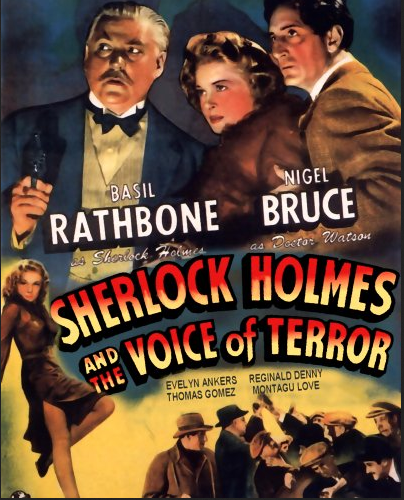

Sherlock Holmes & Voice of Terror

Introduction

Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror exemplifies how women, by the way they think and what they do, are portrayed as key in the plot of a spy noir in the Second World War era.

Main Credits

Director: John Rawlins. Screenplay: Lynn Riggs and John Bright, based on the story “His Last Bow” by Arthur Conan Doyle, adapted by Robert D. Andrews. Producer: Howard Benedict. Cinematographer: Woody Bredell. Music: Frank Skinner. Art Director: Jack Otterson. Editor: Russell F. Schoengarth. Cast: Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes), Nigel Bruce (Doctor Watson), Evelyn Ankers (Kitty), Reginald Denny (Sir Evan Barham), Thomas Gomez (R.F. Meade), Henry Daniell (Anthony Lloyd), Montagu Love (General Jerome Lawford), Olaf Hytten (Fabian Prentiss), Leyland Hodgson (Captain Roland Shore), Robert Barron (Gavin, uncredited), Hillary Brooke (Jill Grandis, driver, uncredited), Mary Gordon (Mrs. Hudson, uncredited), Edgar Barrier (Voice of Terror, voice, uncredited). Released: Universal Pictures, September 18, 1942. 65 minutes.

Presentation

Of all WWII spy noirs, the opening sequence in Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror is exceptionally malevolent. As I explain below, the confidence of the Third Reich and the vulnerability of Britain are time-sensitive representations based on the historical context in which the film was created. In fact, because of this context the film seeks to make its American viewers undeterred – either by Germany’s strength or Britain’s weakness – in giving their full commitment to an Allied victory. The film uses various methods to do this, including stark propaganda, the authority of Sherlock Holmes and, especially, the leadership and sacrifices of a working-class woman. (For a companion analysis of film noir and the working class in the Second World War, see the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs Postwar.)

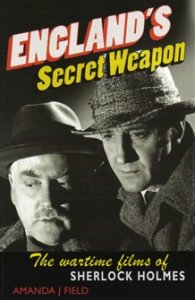

In her overall brilliant study, England’s Secret Weapon: The Wartime Films of Sherlock Holmes, Amanda J. Field describes the opening sequence as follows.

“The Voice of Terror begins with a map of Europe bearing a superimposed graphic of a wave-emitting radio mast and a voiceover that would have been immediately recognizable by contemporary audiences as alluding to Lord Haw-Haw, the British fascist William Joyce who worked for Goebbels, broadcasting messages to Britain…As he speaks…the shadow of the mast moves across the Continent like an invading army until it reaches Britain. The opening shot gives way to a montage sequence that cuts between various groups of wireless listeners including working-class men in flat caps gathered around the radio in their lunch break; nurses; professionals; and middle-class men smoking cigars in their clubs. The ‘voice of terror’ forms a constant background to this montage, which includes scenes of dams collapsing and ships being torpedoed [a different calendar page appears and dissolves as each new disaster is shown]….” (121-122)

“The Voice of Terror begins with a map of Europe bearing a superimposed graphic of a wave-emitting radio mast and a voiceover that would have been immediately recognizable by contemporary audiences as alluding to Lord Haw-Haw, the British fascist William Joyce who worked for Goebbels, broadcasting messages to Britain…As he speaks…the shadow of the mast moves across the Continent like an invading army until it reaches Britain. The opening shot gives way to a montage sequence that cuts between various groups of wireless listeners including working-class men in flat caps gathered around the radio in their lunch break; nurses; professionals; and middle-class men smoking cigars in their clubs. The ‘voice of terror’ forms a constant background to this montage, which includes scenes of dams collapsing and ships being torpedoed [a different calendar page appears and dissolves as each new disaster is shown]….” (121-122)

Below is an excerpt from montage sequence of the “voice of terror.”

The scene ends with a close-up of a newspaper poster that says:

TERROR CAMPAIGN GROWS IN FRIGHTFULNESS!

INTELLIGENCE INNER COUNCIL PROMISES ACTION

Then there is a shot of door with a sign on it that says, “Intelligence Inner Council.” The next scene takes place inside that door.

To solve the mystery of how the Voice of Terror can broadcast each event as it occurs, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are asked to meet with the members of the Intelligence Inner Council. An ominous noir visual style distinguishes the first scene. Across the rear wall of the council’s chamber is a shadow of windowpanes, stretching like a huge spider’s web.

Holmes tells the council that the attacks “are only a prelude, a smokescreen to cover up a more diabolic plan. And I intend to find out what that plan is.”

A man named Gavin is knifed just before he can give vital information to Holmes. As he dies, he gasps one word, “Christopher.” Going back to the late 19th. century, with Holmes’ legacy of solving cases in print, on stage and on screen, one would assume that the great detective himself would conduct the investigation to discover the meaning of that word. After all, he is Sherlock Holmes, and his knowledge of London, and seemingly everything else, is peerless. Such an assumption, however, fails to take into account the historical context when the screenplay was written and when the film was shot (May 6 – May 23, 1942). That is, it was then an open question whether the Allies could defeat the Axis. Therefore, the timing of the film’s creation explains why this Sherlock Holmes lacks his usual unrivaled intellectual prowess. By himself, he is unable to solve the riddle of “Christopher.”

For example, also in the summer of 1942, James Reston’s Prelude to Victory was published. The New York Times journalist, who specialized in diplomatic and foreign affairs, opens Chapter I as follows.

“It is necessary now that we admit the facts: many things we have laughed at, or taken for granted, or minimized, or despised in the last few years have risen up to plague us. The little man with the Charlie Chaplin mustache who merely wanted living space for the Germans and could not attack us even if he wanted to is the master of Europe whose submarines are taking pot shots at our East Coast. The little grinning yellow men, the growers of our vegetables, the makers of our cheap toys, the imitators of the West whom we brought into the modern world and could vanquish in three months, are the conquerors of the East. The people we revered, the immortal French, are stricken down and silent; the people we counted out, the plodding English, are still alive; the great mysterious peoples of the East, the Chinese, who were good enough to wash our shirts, and the Russians, who were not, are helping to save our lives. What is this phantasmagoria? How did this come about? What can we do about it? Where do we stand late in the year 1942?” (3)

The rest of the book is both a wake-up call and a clarion call to Americans that they must dedicate themselves to fighting back. Reston begins Chapter IV unequivocally, “The alternatives before the American people in the closing months of 1942 are both simple and desperate: we must conquer or be conquered; we must learn the lessons of our mistakes or be destroyed by them.” (54)

The rest of the book is both a wake-up call and a clarion call to Americans that they must dedicate themselves to fighting back. Reston begins Chapter IV unequivocally, “The alternatives before the American people in the closing months of 1942 are both simple and desperate: we must conquer or be conquered; we must learn the lessons of our mistakes or be destroyed by them.” (54)

Reston’s writing may not be as dramatic as the opening sequence of Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, but his intent is no different: to alarm if not frighten.

Holmes and Watson venture into “the dark and sinister alleys of Limehouse,” an East End district in London populated by the working class – and criminals. A tough guy recognizes Holmes and warns him to go away because “we don’t fancy your sort of bloke in these parts.” A thrown knife narrowly misses Holmes. Watson is eager to leave Limehouse, but Holmes refuses.

They enter an underground beer hall. An old man takes them to a table, and Holmes asks him, “Where’s the girl, Kitty, Gavin’s sweetheart?” “His wife,” the man responds. Holmes says, “Can you get her? It’s urgent.”

Kitty arrives at the beer hall looking for Gavin. She goes to the table where Holmes and Watson are sitting. Holmes needs Kitty to find out the meaning of Gavin’s last word. He believes that only she can persuade the men and women in the beer hall to help out with the investigation. In other words, unwillingness to join the fight against the Nazis must be overcome. At first Kitty refuses to help, since it would mean aiding the police, whom she and those of her social class despise. In a remarkable scene, shown below, Holmes pleads with her, arguing that she (a woman) has the most intimate knowledge of their city, and only she can mobilize and lead her friends (proletarians) to find out the meaning of “Christopher.” In other words, unwillingness to join the fight against the Nazis must be overcome.

Kitty, because she is working class, can succeed where Holmes would fail. In the series of Sherlock Holmes films in which, according to Amanda J. Field, he is “England’s Secret Weapon,” only in The Voice of Terror does he have to rely on someone else to solve a mystery. But this situation shouldn’t seem, as Reston might say, phantasmagorical. The Voice of Terror is different because its timing was close to the nadir of the prospects for the Allies’ victory.

Convinced by Holmes, Kitty walks from one table to another asking what “Christopher” means. No one is willing to help her.

Standing before everyone, she makes a speech, in the scene below. What Kitty wants to do with her suspicious listeners is what James Reston wants to do with his skeptical readers: convince them that their country and, indeed, their freedom are at stake. In fact, the audiences are comparable for Kitty and Reston. In the beer hall it is the working class of the Limehouse; in the American movie theaters it is people of all walks of life. For the British in the film, Kitty’s speech is class-collaborationist and nationalistic propaganda. For the Americans watching the film, it is a post-Pearl Harbor cross-class rallying cry.

When she finishes so successfully, Holmes says, “Thank you, Kitty,” and Dr. Watson adds, “Well done, my dear.”

Once Kitty reports to Holmes the meaning of “Christopher,” she undertakes a much greater challenge. Although Holmes has promised that he will “find out what [the Nazis’s] plan is,” what he actually does is hatch a scheme whereby Kitty “accidentally” meets a top Nazi, Meade, as shown below in two parts. To get Meade to reveal the Germans’s plan to invade and conquer Britain, Kitty agrees to risk her life to seduce him and become his mistress.

Thoroughly deceived, Meade takes Kitty with him to the place on the southern coast where the Germans are going to invade Britain. One of her recruits, a cab driver, learns the location by following Kitty, and he reports back to Holmes. Unquestionably, it is Kitty, at least as much as Holmes (“England’s Secret Weapon”), who saves Britain.

Holmes, Watson and the members of the Intelligence Inner Council race from London to a bombed out church on the coast. Inside its ruins they find Kitty as well as Meade and his accomplices. The invasion is thwarted, and “the scattered Nazi agents all over the Commonwealth [are] unceremoniously clapped into prison.”

Holmes then reveals that the ringleader behind the Voice of Terror is the chief of the council, Sir Evan Barham. What matters aren’t the details of the deus ex machina in Holmes’s exposure of Sir Evan as a German imposter, who replaced the real British aristocrat as far back as World War One. (It is just one example in spy films of the Germans’s long-term planning.) What is significant is that the denouement reverses a common plot device in WWII spy films, in which a “double” turns out to be a good spy. This film flips the classic espionage deception of The Great Impersonation. (E. Phillips Oppenheim’s novel was published in 1920, and a spy noir based on the book was released three months after The Voice of Terror, which was also directed by John Rawlins.)

Avenging himself for being duped by Kitty, Meade grabs a gun and kills her; then he himself is killed fleeing from the church. It might be said that Kitty’s death is Hollywood’s retribution for her sexual code-breaking. Amanda J. Field considers it evidence that Kitty is “dispensable” and “expendable.”

“In the Holmes films…[before 1943], success had depended on a supreme being: the little people, like Kitty in Voice of Terror, were seen to be dispensable once their purpose had been served.” (137)

“[T]he narrative concentrates on her ‘use-value’ in rallying the criminal classes against the Nazis,” and “sleeping with the enemy in order to get information…Kitty is a working-class woman and the underlying message in her portrayal is that these women are expendable in a way that middle-class women are not: they serve their country with their bodies, through sex or dying….” (180)

As I have argued above in terms of the historical context of the film, Sherlock Holmes isn’t “a supreme being.” If he were, he wouldn’t have to beg Kitty to get her friends to solve for him the mystery of “Christopher.”

Besides Kitty, other women in spy noirs sleep with the enemy. When she is a wife, she outlives her husband and then has real love with another man, who is a hero on her side: Paris Calling (1941), First Comes Courage (1943), The Man from Morocco (1945), and Notorious (1946). When she is a mistress, the man kills her in revenge for her duplicity: Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1942), Lady from Chungking (1942) and Edge of Darkness (1943). In The Spy in Black, a female British secret agent pretends to be a German spy. She tells a real German spy that, in order to make plans to destroy a British fleet, they are getting help from “a British naval officer with a grudge against the service.” He has no objection or regret when she says the traitor’s “rather high” price was paid by Germany “and me.” (For an in-depth analysis, see the page The Spy in Black.)

Even ignoring the pro-Axis “bad” women, the list of pro-Allies “good” women who die in spy noirs is lengthy. They are not only working class but also “middle class.” I don’t consider any of their lives as dispensable or expendable. There was a war on, and dealing with death was something that movie-goers had to come to grips with. Kitty is an example of one of the aspects of my definition of the WWII spy noir: “In many crime noirs, characters that die may be unfamiliar or unsympathetic to audiences. In contrast, during a time when so many film viewers had lost loved ones, characters in spy noirs are regularly killed off after audiences have come to understand and admire them.” (For my full exposition about spy noirs, including references to and video clips of “middle class” women who die, see the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.)

In an earlier scene, after Kitty finds out the meaning of “Christopher,” she comes to the headquarters of the Intelligence Inner Council. A guard announces her, “Mr. Holmes, there’s a person outside asking….” Holmes says, “A lady?” The guard replies, “Umm.” Holmes stands up and says, “Ask her to come in.” Throughout the film, Holmes shows respect for Kitty, whether at the beer hall or in front of the council members. In contrast, commentators about the film degrade her. For example, Field cites, without disapproval, Bernard Dick’s denigrating view of the relationship between Kitty and Holmes: “Dick is disturbed by Holmes’ manipulation of Kitty, the East End bar girl.” (135) In the booklet for the DVDs in The Sherlock Holmes Collection: Volume One, Richard Valley says, “Most likely Holmes is right and Kitty is the dead man’s lover – and quite possibly a prostitute.”

To assert that Kitty is Gavin’s “lover” is preposterous. She confronts Holmes because she is looking for her husband. Kitty’s relationship with Gavin is established by an unidentified man at the beer hall who corrects Holmes for saying Kitty is Gavin’s “girlfriend.”

I disagree that Holmes “manipulates” Kitty. Holmes tells her the truth: “the Nazis” murdered Gavin. That riles her up, and she wants to get even. Additionally, there is no evidence that Kitty is a streetwalker. Or could it be her attire? Are the clothes of Hollywood’s version of an East End working class woman what makes her appear to commentators as a bar girl, a prostitute?

Field sees Holmes’ reaction to Kitty’s murder as callous. “[W]hen she is shot, Holmes barely pauses to pay tribute to her before stepping around her corpse to deliver his Shakespearian ‘East Wind’ speech.” (180) In this single sentence Field commits three errors of fact.

First, Field’s contention that Holmes “barely pauses to pay tribute to [Kitty]” is wrong. In a eulogy for Kitty, Holmes says, “This girl merits our deepest gratitude. Our country is honored in having such loyalty and devotion.” A member of the Inner Council responds, “We’ll remember.”

Second, Field is mistaken to say that Holmes is shown “stepping around her corpse.” Instead, he simply steps away from her, while Watson stays behind to “see that she’s taken care of.” Moments later, in the film’s final scene, Holmes and Watson walk outside the church and look out at the English Channel.

Third, Field’s stating that Holmes delivers a “Shakespearian ‘East Wind’ speech” conflates two different authors, two different speeches and two different films. Several months after The Voice of Terror, the next entry in the series, Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon, was released. (The Los Angeles premiere was December 25, 1942, and the general release was February 12, 1943.) It is a spy film, not a spy noir, and it concludes as follows. Watson says, “Well, this little island is still on the map.” In response, Holmes quotes from Shakespeare’s Richard II (Act II, Scene 1): “This fortress built by Nature for herself…This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.”

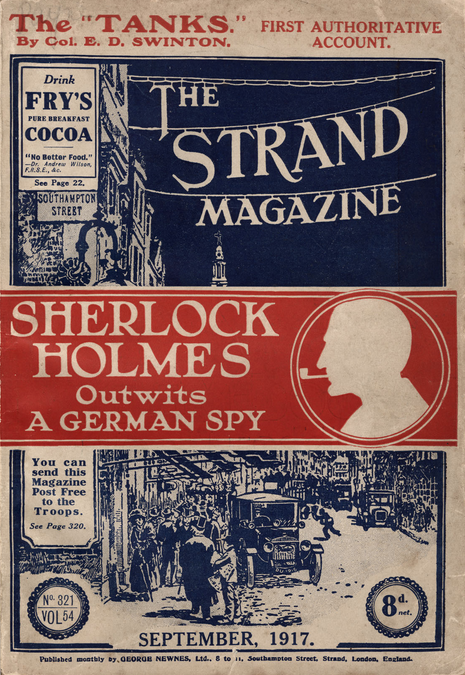

The East Wind speech isn’t from Shakespeare, but rather comes from the end of “His Last Bow,” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s story on which The Voice of Terror is (loosely) based. The clip below from the film’s conclusion begins with Watson’s concern for Kitty (ignored by Field) and ends with the East End Speech.

“His Last Bow” was first published in Britain in The Strand Magazine in September 1917, a year after the battle of the Somme and before the battle of Passchendaele – another public shocker of ghastly carnage – was finished.

“His Last Bow” was first published in Britain in The Strand Magazine in September 1917, a year after the battle of the Somme and before the battle of Passchendaele – another public shocker of ghastly carnage – was finished.

As noted by Lawrence Sondhaus in World War One: The Global Revolution, the first day at the Somme, July 1, 1916, was “the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army…[with] a staggering 54,470 casualties including 19,240 men killed, most of them by machine-gun fire…The action at the Somme finally ended on November 18.” Total British and Imperial casualties were 420,000 including 146,000 killed. (213-214)

The battle of Passchendaele lasted from July 31-November 10, 1917. Sondhaus says, “Other than the Somme, Passchendaele ranked as the British Empire’s costliest battle of the war.” (257)

The context in which Americans heard the lines by Holmes and Watson in the film echoes the context in which British read them in the story. Holmes’ speech acknowledges and commemorates the sacrifice of lives, like Kitty’s, that has to be endured. For the audience in each World War, the message is the same: as dark as the times are now and may remain in the days ahead, hope and resolve to win the war must not waver.

From my analysis of Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, I have a different interpretation of Kitty than Amanda J. Field. I don’t find Kitty to be merely use-value, dispensable or expendable. Instead, I see her as among a cross-class British-American sisterhood, comprised of a wide range of female characters in spy noirs, in which women match men as doers, leaders and thinkers.

For more about women in spy noirs in the WWII era, see the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.

Addendum I: Background about the film

After its release in the US, Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror was not released in Britain for over a year, until October 1943. For this reason I have associated the film’s historical context (mid-1942) solely with an American audience.

Of the 14 films starring Basil Rathbone, Sherlock Holmes and The Voice of Terror has the strongest and most consistent noir visual style. For example, in the series the noir style is never more impressive than the sequence in the streets of Limehouse, inside the beer hall and when Kitty “accidentally” meets Meade. The achievement of the film’s mise-en-scène is mainly attributable to the director, John Rawlins, and the cinematographer, Woody Bredell. This is the only film in the series that Rawlins and Bredell worked on.

Rawlins’ film noirs are all spy noirs: Mister Dynamite (1941), Bombay Clipper (1942), Sherlock Holmes and The Voice of Terror (1942), Unseen Enemy (1942), and The Great Impersonation (1942).

Among cinematographers, Bredell’s film noir credits are outstanding: Phantom Lady (1942), Sherlock Holmes and The Voice of Terror (1942), Christmas Holiday (1944), Lady on a Train (1945), Smooth as Silk (1946), The Killers (1946), Tangier (1946), The Unsuspected (1947), and Female Jungle (1956).

Underscoring my perspective about Sherlock Holmes and The Voice of Terror is the following entry for the film in Blacklisted: The Film Lover’s Guide to the Hollywood Blacklist by Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner.

“John Bright co-scripted this most class-conscious story of a present-day Holmes, discovering a Nazi spy is a ruling class imposter, brought down with the help of the subterranean masses of London.” (199).

Bright was a founder of the Screen Writer’s Guild.

Addendum II: Background about Nazi propaganda for “The Voice of Terror”

The following quotation comes from the essay by Jochen Hellbeck, “Battle for Morale: An entangled history of total war in Europe, 1939-1945” in The Cambridge History of the Second World War: Volume III, Total War: Economy, Society and Culture.

“On 18 September 1939, Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda ministry launched an English-language new station based in Hamburg. It featured nightly broadcasts aimed at the United Kingdom seeking to weaken British war resolve. The British press ridiculed the broadcasters, some of whom spoke with comically upper-class accents, as ‘Lord Haw-Haw.’ But these broadcasts drew an estimated 6 million British listeners in 1939 and 1940, partly because they provided details on British military losses, about which the BBC remained silent. ‘Lord Haw-Haw’s’ reporting not only detailed military events, it also targeted social, economic and political problems in British life, ranging from Britain’s enduring slum system and mass unemployment to the cruel colonial practices of the British Empire. In addressing these themes, the broadcasts celebrated National Socialist achievements, thereby presenting Nazi Germany as a revolutionary order committed to social justice.

“On 18 September 1939, Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda ministry launched an English-language new station based in Hamburg. It featured nightly broadcasts aimed at the United Kingdom seeking to weaken British war resolve. The British press ridiculed the broadcasters, some of whom spoke with comically upper-class accents, as ‘Lord Haw-Haw.’ But these broadcasts drew an estimated 6 million British listeners in 1939 and 1940, partly because they provided details on British military losses, about which the BBC remained silent. ‘Lord Haw-Haw’s’ reporting not only detailed military events, it also targeted social, economic and political problems in British life, ranging from Britain’s enduring slum system and mass unemployment to the cruel colonial practices of the British Empire. In addressing these themes, the broadcasts celebrated National Socialist achievements, thereby presenting Nazi Germany as a revolutionary order committed to social justice.

“Compared with the sophistication of Goebbels’s propaganda machine, British efforts to mould public morale in the early phase of the war appeared feeble and quaint. British leaders recognized Nazi Germany’s edge in disseminating effective propaganda, yet they hesitated to answer in kind, lest they also appear totalitarian. On 4 September 1939, the government activated the Ministry of Information, which had been planned since 1935…Internal government documents from the first months of the war spoke os a sense of moral uncertainty, which turned into full-fledged political crisis when on 10 May 1940 Germany invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and France…Later in May, the Ministry of Information foresaw a rise in ‘fear, confusion, suspicion, class-feeling, and defeatism’ among the British population…Clearly Germany’s harping on British social inequities was on the minds of British government officials, who conceded the ‘revolutionary’ quality of the Nazi order and were under pressure to develop a firm response, in both military and social terms.” (331-332)

Bibliography

Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, Blacklisted: The Film Lover’s Guide to the Hollywood Blacklist (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

Amanda J. Field, England’s Secret Weapon: The Wartime Films of Sherlock Holmes (Middlesex University Press, 2009)

Michael Geyer and Adam Tooze, editors, The Cambridge History of the Second World War: Volume III, Total War: Economy, Society and Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

James B. Reston, Prelude to Victory (Alfred A. Knopf, 1942)

Lawrence Sondhaus, World War One: The Global Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2011)