Significance of the Woman in Distress

Historic Absence of Attention to the Woman in Distress in Film Noir Literature

In 1987, while writing an essay, “The Rise and Fall of the War Noir,” I set down my first criticism about the failure to address the woman in distress in published literature on film noir, whether in mainstream media articles or academic texts. When the essay was included in Alain Silver and James Ursini’s Film Noir Reader 4 (Limelight Editions, 2004), still no attention had been paid to this paramount film noir character. (For a discussion of an exception to this statement, which barely counts as such, see the Addendum at the end of this page.)

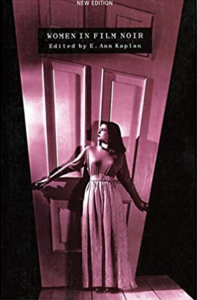

The “New Edition” of Women in Film Noir (British Film Institute, 1998), edited by E. Ann Kaplan, like the first edition (1978), ignores the woman in distress. In her essay, “Women in Film Noir,” Janey Place identifies only two types, spider women (aka femme fatales) and nurturing women (aka redeemers) (53, 60). An essay by Angela Martin is about “The Central Women of 40s Film Noirs.” In an Appendix, she describes eleven “Character and theme strands.” The closest to the woman in distress is “Victims of psychotic males,” which of course is severely limiting. On the same page, under “Bad blood relatives,” inconsistently referring to exactly another such “victim,” Martin says, “In Dragonwyck, Gene Tierney’s character marries a wealthy cousin who turns out to be psychotic” (221). Also “inconsistently,” despite no discussion in the text of the woman in distress and no reference in it to this film, the book’s cover picture is of Joan Bennett from Secret Beyond the Door, a classic film noir of a woman in distress!

The “New Edition” of Women in Film Noir (British Film Institute, 1998), edited by E. Ann Kaplan, like the first edition (1978), ignores the woman in distress. In her essay, “Women in Film Noir,” Janey Place identifies only two types, spider women (aka femme fatales) and nurturing women (aka redeemers) (53, 60). An essay by Angela Martin is about “The Central Women of 40s Film Noirs.” In an Appendix, she describes eleven “Character and theme strands.” The closest to the woman in distress is “Victims of psychotic males,” which of course is severely limiting. On the same page, under “Bad blood relatives,” inconsistently referring to exactly another such “victim,” Martin says, “In Dragonwyck, Gene Tierney’s character marries a wealthy cousin who turns out to be psychotic” (221). Also “inconsistently,” despite no discussion in the text of the woman in distress and no reference in it to this film, the book’s cover picture is of Joan Bennett from Secret Beyond the Door, a classic film noir of a woman in distress!

In 2010, Andrew Spicer’s Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (The Scarecrow Press, Inc.), had a three-page entry for “WOMEN,” with the following paragraph that, although offering meager coverage of the topic, at least was something.

“Noir’s debt to horror included the figure of the imperiled female victim, notable in the early Gothic noirs where they are psychologically abused and physically threatened by the deranged homme fatal – Joan Fonataine in Suspicion (1947), Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight (1944), Heddy Lamarr in Experiment Perilous (1944), Gene Tierney in Dragonwyck (1946), Dorothy McGuire in Robert Siodmak’s The Spiral Staircase (1946), or Joan Bennett in Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door (1948). This scenario was transferred to a contemporary setting as in The Arnelo Affair (1947) or Cause for Alarm (1951), where suburban housewives are the victims of their husband’s obsessive jealousy.” (330)

Below I show that “imperiled,” like the term “woman in peril,” inaccurately describes women who are “psychologically abused,” as in Suspicion, Gaslight and The Arnelo Affair.

In 2013, whatever this female film noir character is called, an opportunity to discuss her was ignored in A Companion to Film Noir (Wiley-Blackwell), edited by Andrew Spicer and Helen Hanson. This anthology has a single essay about “Women in Film Noir.” In its fourteen pages the author, Yvonne Tasker, never even once mentions a woman troubled by psychologically or physically based plight. Although in the index of the book there are many references to “femme fatale,” there is no entry for “woman in distress” or a similar term.

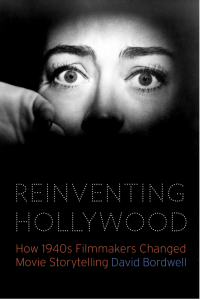

In 2017, important progress came with the publication of David Bordwell’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling (University of Chicago Press, 2017). Bordwell discusses the “woman in peril plot.” He contends it is a new kind of “thriller,” which is psychological, in contrast to earlier thrillers associated with “international intrigue” and “hard-boiled detectives.” He says, “While other genres, such as the war film, put their characters in danger, the psychological thriller makes suspense the dominant emotion of the film. It demands that the film focus on the potential victim” (384-385).

To define suspense, Bordwell quotes Patricia Highsmith, “who proposed that suspense entailed ‘a threat of impending violent action.’ In the purest cases of 1940s suspense, a sympathetic character is put in great danger and pitted against a menace that will stop at nothing” (384).

Although he doesn’t refer to them as film noirs, Bordwell’s examples of psychological thrillers are all film noirs with a woman in distress that are included in my table in Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale. The book’s cover picture is of Joan Crawford from Sudden Fear, which, like the cover of Women in Film Noir, comes from a film noir of a woman in distress.

Why “Woman in Distress” Is the Correct Term

David Bordwell has made a major contribution to the film noir literature by showcasing the character that he calls the woman in peril. Yet, as I explain below, his term isn’t valid.

First, because of Bordwell’s use of Patricia Highsmith’s definition of suspense (“a sympathetic character is put in great danger”), he contradicts his claim that the psychological thriller is different from “other genres, such as the war film.” The reason is that he says those other genres also “put their characters in danger.”

Second, because of Bordwell’s use of Patricia Highsmith’s definition of suspense (“a threat of impending violent action”), the plight of a woman must be physically based. But in a “psychological” thriller one has to assume that a woman’s plight is, instead, mentally based.

Before explaining why Bordwell’s term, woman in peril, is inappropriate, let’s look more closely at the problems raised, on the one hand, by his association of suspense with “a threat of impending violent action” and, on the other hand, with his association of this meaning of suspense with the psychological thriller.

The online dictionary, Merriam-Webster, defines the noun, suspense, as follows.

Definition of SUSPENSE

1 : the state of being suspended : suspension

2 a : mental uncertainty : anxiety

b : pleasant excitement as to a decision or outcome

• a novel of suspense

3 : the state or character of being undecided or doubtful : indecisiveness

How can it be legitimate for Bordwell to use Highsmith’s personal definition of suspense when it is in clear contradiction with the dictionary definition? The latter makes no reference to violent action, “impending” or otherwise. It doesn’t suggest that suspense is associated with anything physical, such as violence. It only associates suspense with something mental, such as uncertainty or anxiety.

Furthermore, how can it be legitimate for Bordwell to use Highsmith’s definition of suspense, which pertains to the physical (a threat of impending violent action), in association with the psychological thriller? Highsmith’s definition of suspense is contradictory to the inherent meaning of psychological. (For example, see Wikipedia about psychological thriller.)

Finally, regarding his term, woman in peril, because of the dictionary definition of suspense, how can it be legitimate for Bordwell to associate peril with suspense and the psychological thriller?

Merriam-Webster defines the noun, peril, as follows.

Definition of PERIL

1 : exposure to the risk of being injured, destroyed, or lost : danger

• fire put the city in peril

2 : something that imperils or endangers : risk

• lessen the perils of the streets

Contrary to Bordwell, it cannot be assumed a woman in a psychological thriller will experience the threat of impending violent action. Take Gaslight (1944), one of Hollywood’s earliest psychological thrillers and still among the most famous. It is based on Patrick Hamilton’s British stage play, Gas Light (1938), and the British film noir, Gaslight (1940). In each rendition, a wife’s husband does things to make her believe she is losing her mind. He wants her to become convinced she cannot trust her own sanity so that she will agree to be institutionalized. Once she is out of their house, he can search for her aunt’s valuable jewels by day, not only at night. In his plan, there is no threat of violence against her.

Contrary to Bordwell, it cannot be assumed a woman in a psychological thriller will experience the threat of impending violent action. Take Gaslight (1944), one of Hollywood’s earliest psychological thrillers and still among the most famous. It is based on Patrick Hamilton’s British stage play, Gas Light (1938), and the British film noir, Gaslight (1940). In each rendition, a wife’s husband does things to make her believe she is losing her mind. He wants her to become convinced she cannot trust her own sanity so that she will agree to be institutionalized. Once she is out of their house, he can search for her aunt’s valuable jewels by day, not only at night. In his plan, there is no threat of violence against her.

The very title of this story has entered the English language. Merriam-Webster defines the verb, gaslight, as follows.

Definition of GASLIGHT

gaslighted; gaslighting

: psychological manipulation of a person usually over an extended period of time that causes the victim to question the validity of their own thoughts, perception of reality, or memories and typically leads to confusion, loss of confidence and self-esteem, uncertainty of one’s emotional or mental stability, and a dependency on the perpetrator

Origin and Etymology of GASLIGHT

after Gas Light, a play (1938) by British writer Patrick Hamilton, subsequently made into British and American films entitled Gaslight (1940 and 1944), in which a man attempts to trick his wife into believing that she is going insane

First Known Use: 1956

[Update: This webpage was posted in 2018. In 2022, Merriam-Webster designated “gaslighting” as its official word of the year.]

Besides Gaslight, there are numerous film noirs in which a woman’s plight isn’t physically based (such as the threat of impending violent action) but is, instead, psychologically based (such as anxiety, suspicion or fear). The following are just a few examples.

In Casablanca (1942), a woman makes an excruciating choice between two men when, in the context of World War II, her decision must weigh political responsibility against true love. In The Arnelo Affair (1947) a wife is afraid to end an affair because her lover threatens to go to the police and implicate her in a murder, which would destroy her marriage as well as her husband’s career.

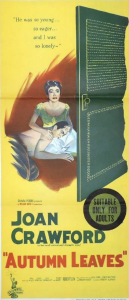

There are marriages in which a wife is miserable, not because she feels her life is in danger but because she believes that her husband doesn’t love her. She may be right, as in Caught (1949) or she may be wrong, as in Rebecca (1940). In Autumn Leaves (1956) a wife fears losing her husband after he has a mental breakdown upon discovering that his ex-wife is his father’s mistress. Other wives suffer because their husbands are suffering, too. It may be because of his awful past personal experiences, as in Daisy Kenyon (1947), or his failed business career, as in Death of a Salesman (1952), or his drug addiction, as in A Hatful of Rain (1957) and Monkey on My Back (1957).

There are marriages in which a wife is miserable, not because she feels her life is in danger but because she believes that her husband doesn’t love her. She may be right, as in Caught (1949) or she may be wrong, as in Rebecca (1940). In Autumn Leaves (1956) a wife fears losing her husband after he has a mental breakdown upon discovering that his ex-wife is his father’s mistress. Other wives suffer because their husbands are suffering, too. It may be because of his awful past personal experiences, as in Daisy Kenyon (1947), or his failed business career, as in Death of a Salesman (1952), or his drug addiction, as in A Hatful of Rain (1957) and Monkey on My Back (1957).

In Behind Green Lights (1946), a woman isn’t intentionally framed for killing a man who was blackmailing her, but she is the most likely suspect until the real murderer is discovered. Similarly, in The Blue Gardenia (1953), circumstantial evidence suggests a drunk woman murdered a man with a poker when she fought off his sexual assault in his apartment.

Many more examples could be added. The point is, if the term woman in peril doesn’t accurately pertain to each and every woman in plight in film noir, then it must be replaced with one that does.

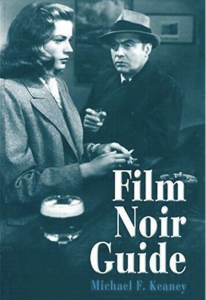

Another term that has been used is woman in jeopardy. For example, Michael Keaney, in Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959 (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), includes woman in jeopardy among the “Noir Themes” in Rebecca (353). In “Appendix B: Film Noirs Listed by Type,” Keaney cites “Femme Fatale” as a type, but not woman in jeopardy (488). In fact, woman in jeopardy is as inappropriate a term as woman in peril, and for the same reason.

Another term that has been used is woman in jeopardy. For example, Michael Keaney, in Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959 (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), includes woman in jeopardy among the “Noir Themes” in Rebecca (353). In “Appendix B: Film Noirs Listed by Type,” Keaney cites “Femme Fatale” as a type, but not woman in jeopardy (488). In fact, woman in jeopardy is as inappropriate a term as woman in peril, and for the same reason.

Merriam-Webster defines the noun, jeopardy, as follows.

Definition of JEOPARDY

1: exposure to or imminence of death, loss, or injury : danger

• placing their lives in jeopardy

• workers in jeopardy of losing their jobs

Based on the dictionary definition of jeopardy, the wives in Gaslight and Rebecca aren’t women in jeopardy because neither they (nor the other women in my examples above) are endangered by “exposure to or imminence of death, loss or injury.”

If peril and jeopardy are inaccurate, what is the correct word? It is “distress,” and it has been part of cinema history since Hollywood’s silent era. At that time, a woman tied to the railroad tracks was said to be a “damsel in distress.” (Wikipedia’s history of the term, damsel in distress, begins centuries earlier.)

Whether threatened with the loss of her life by an oncoming train or imagining that she is going mad, the term woman in distress accurately describes a woman’s physical as well as her psychological plight.

Merriam-Webster defines the noun, distress, as follows. (The first category, law, is irrelevant.)

Definition of DISTRESS

1 law

a : seizure and detention of the goods of another as pledge or to obtain satisfaction of a claim by the sale of the goods seized

b : something that is distrained

2 a : pain or suffering affecting the body, a bodily part, or the mind : trouble

• gastric distress

• The patient showed no obvious signs of distress.

• severe emotional distress

• voiced their distress over the delays

b : a painful situation : misfortune

3 : a state of danger or desperate need

• a ship in distress

The term woman in distress covers the full range of a woman’s plight, which includes the physical (“pain or suffering affecting the body”) as well as the psychological (“pain or suffering affecting…the mind”). Furthermore, distress also pertains to “a state of danger,” which is analogous to peril. A woman in distress is the most all-encompassing term and, therefore, the most accurate.

Variations of the Woman in Distress in Film Noir

As argued above, there are two kinds of women in distress in film noir: one whose plight is physical and the other for whom it is psychological. In the plots of films, there is a wide variation of how either plight is experienced, and what the outcome is.

A woman in distress may be the central character or a secondary one. What I want to underscore is that she is one of the most recurring characters in film noir. Furthermore, it isn’t unusual to have two women in distress in the same film.

Two of the key aspects in a plot are the length of run-time in which a woman is in distress and the intensity with which she experiences her plight. Between the two aspects, there isn’t a necessary correlation. That is, great intensity of a woman’s plight may have a short run-time. Similarly, this duration doesn’t imply how strong the feeling of suspense is.

In the opening scene of Sorry, Wrong Number (1948), a bedridden wife is upset after she accidentally overhears a phone conversation in which two men discuss the murder of a woman later that night. By the final scene she is terrified as the murderer approaches her. From the moment she realizes someone is downstairs to her final scream it is only four and a half minutes of run-time.

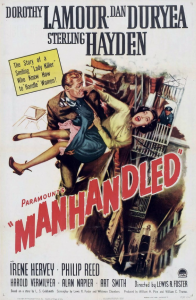

In Manhandled (1949), a woman doesn’t know that a man she considers a friend has framed her for both a jewel robbery and a murder. It isn’t until almost the film’s end when she discovers the truth. To prevent her from exposing him to the police, he knocks her out and carries her to their building’s rooftop, where he is going to throw her over, as if she killed herself. Just in time, she comes to, screams and is rescued by the cops. All this lasts three and a half minutes.

In these two films, there is near parity in the run-time of a woman’s endangerment, but a huge difference in her plight’s intensity and the level of suspense. Sorry, Wrong Number is memorable; Manhandled is forgettable.

With only twenty minutes remaining in Notorious (1946), a wife begins to be incrementally poisoned by her husband. At first, only the audience knows what is happening. Over seven minutes pass before she discovers her increasing debilitation comes from the coffee she drinks. While the run-time when she knows she is being killed is relatively brief, the intensity that her danger is depicted, including before her own realization of it, ranks among the very strongest in film noir.

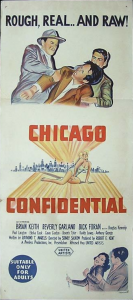

The woman in distress hasn’t only been ignored in film noir literature; she may be dismissed in the film in which she plays a key role. In the final scene of Chicago Confidential (1957), referring to a state’s attorney, a voice-over says, “And on James Freemont’s desk was proof [a reel-to reel tape] that the high office of our land cannot be corrupted if men of courage are willing to fight for what is right and decent.” (Under the tape is an issue of Newsweek magazine, whose cover has his picture and the banner, “Union Racket Buster Boomed for Governor.”) All of this is false. The wife of a union president, who the attorney had convicted of murder based, in part, on a tape recording, repeatedly appeals to him to reconsider the evidence. Finally, he has the voice on the tape compared with a tape of the actual voice of the man facing execution. Scientific technology demonstrates the voices are from different men. The film has two women in distress: the woman in love with the man on death row and a key witness at the trial, who, to save her life, union racketeers forced to change her testimony. In the film’s climax, the women survive a plan kill them. Although the lover of the released prisoner is the true heroine, the film honors, instead, the state’s attorney, whom she had to cajole to do his job “for what is right and decent.”

The woman in distress hasn’t only been ignored in film noir literature; she may be dismissed in the film in which she plays a key role. In the final scene of Chicago Confidential (1957), referring to a state’s attorney, a voice-over says, “And on James Freemont’s desk was proof [a reel-to reel tape] that the high office of our land cannot be corrupted if men of courage are willing to fight for what is right and decent.” (Under the tape is an issue of Newsweek magazine, whose cover has his picture and the banner, “Union Racket Buster Boomed for Governor.”) All of this is false. The wife of a union president, who the attorney had convicted of murder based, in part, on a tape recording, repeatedly appeals to him to reconsider the evidence. Finally, he has the voice on the tape compared with a tape of the actual voice of the man facing execution. Scientific technology demonstrates the voices are from different men. The film has two women in distress: the woman in love with the man on death row and a key witness at the trial, who, to save her life, union racketeers forced to change her testimony. In the film’s climax, the women survive a plan kill them. Although the lover of the released prisoner is the true heroine, the film honors, instead, the state’s attorney, whom she had to cajole to do his job “for what is right and decent.”

Another of the variations in plots pertains to the outcome for the woman in distress. Sometimes she dies. For example, the wife is murdered in Sorry, Wrong Number (and there is no doubt her husband gets away with arranging her death). More often, as in Notorious, the woman survives. Because he failed to poison her, her husband’s Nazi colleagues will kill him, and she will be able to marry the U.S. government agent who rescued her. In Gaslight, the wife survives, but she exacts a measure of revenge on her husband before he is arrested by the Scotland Yard officer who will be the man she shares love with in the future.

A woman in distress isn’t necessarily a victim. Despite, typically, being unable to resolve her plight by herself, there are exceptions. In No Man of Her Own (1950), a pregnant wife dies in a train crash. Another expecting woman is wearing the deceased’s wedding ring. She impersonates the wife to raise her own child in a well-to-do family. When an ex-lover tries to blackmail her, she goes to his hotel room and fires a gun at him. He may have already been dead, but what matters is that she would kill to prevent her exposure and a scandal that would harm the family that loves her.

A woman in distress isn’t necessarily a victim. Despite, typically, being unable to resolve her plight by herself, there are exceptions. In No Man of Her Own (1950), a pregnant wife dies in a train crash. Another expecting woman is wearing the deceased’s wedding ring. She impersonates the wife to raise her own child in a well-to-do family. When an ex-lover tries to blackmail her, she goes to his hotel room and fires a gun at him. He may have already been dead, but what matters is that she would kill to prevent her exposure and a scandal that would harm the family that loves her.

Before the table in Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale, I cite 26 film noirs with both a woman in distress and a femme fatale.

In Shadow on the Wall (1950), the femme fatale’s target is a young girl, not a grown-up woman.

Just as a girl may be a femme fatale, as in The Bad Seed (1956), there are film noirs besides Shadow on the Wall with a girl in distress (but without a femme fatale), such as Hitler’s Children (1942), Curse of the Cat People (1944) and The Lineup (1958).

There are three special film noirs in the “classic era” (1940-1959), in which the same character is both a woman in distress and a femme fatale (or vice versa).

In The Last Crooked Mile (1946), a woman begins, we believe, as a woman in distress, but she ends, in plot twist, as a femme fatale. (For details, see the page The Killer Client & the PI.)

In the other two, the same woman begins as a femme fatale and ends as a woman in distress: Roadblock (1951) and Vertigo (1958).

In Roadblock, a very greedy woman rebuffs an insurance detective because his salary is so low, although she loves him. She changes her mind and marries him, but it is too late for their happiness. To get the money he thinks he needs to satisfy her, he has masterminded a train robbery, which takes place while they are on their honeymoon. After his insurance company partner figures out his guilt, he takes her in a car chase with the police along the Los Angeles river bed. Moments after he stops and pushes her out of the vehicle, he is shot dead. She ends up alone, perhaps to go to Texas where her former married lover is now free to wed her.

For an extensive analysis of the film noir that is an exemplar of both the femme fatale and the woman in distress, see the page Vertigo.

For an extensive analysis of the film noir that is an exemplar of both the femme fatale and the woman in distress, see the page Vertigo.

Gilda: The Woman in Distress rather than the Femme Fatale

A controversial issue is whether women who have been called femme fatales in film noir literature are, instead, women in distress. For example, although proponents of the hardboiled paradigm have cited Gilda as a femme fatale, the film doesn’t support this claim. Therefore, in the table in Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale, I include Gilda (1946) in the woman in distress column, not the femme fatale column.

A controversial issue is whether women who have been called femme fatales in film noir literature are, instead, women in distress. For example, although proponents of the hardboiled paradigm have cited Gilda as a femme fatale, the film doesn’t support this claim. Therefore, in the table in Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale, I include Gilda (1946) in the woman in distress column, not the femme fatale column.

Significantly, the femme fatale, as represented by the hardboiled paradigm, has been challenged by Julie Grossman in Rethinking the Femme Fatale in Film Noir: Ready for Her Close-Up (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). She analyzes “misreadings of women, first by men whom they encounter within the films, and second, by film viewers and critics who then perpetuate, and eventually institutionalize, these misreadings.” (41)

For example, Grossman suggests why Gilda may be seen as a woman in distress.

“Gilda provides a good example of the problem with generalizing about representations of women in film noir. In 1956, Jacques Siclier wrote about ‘the relentless misogyny’ in film noir, noting about Rita Hayworth that her role was to ‘Be beautiful and keep silent…she has nothing to say’ [quote from R. Barton Palmer, Perspectives on Film Noir, G. K. Hall, 1996, p. 70]. In fact, Hayworth’s ‘crime’ in Gilda may be that she speaks up. Gilda reveals that what’s fatal in the ‘femme fatale’ is the persistent ideation surrounding women. She calls attention to the victimization of women: first, through her several performances of ‘Put the Blame on Mame’ (one, plaintively; one, humming; one, aggressively, as part of her striptease); second, through her use of language as a weapon. Gilda in fact silences Johnny [Glenn Ford] when she implicitly refers to the sexual meaning of ‘dancing,’ and disarms Johnny when she feminizes him by repeatedly referring to him as ‘pretty.’ Gilda’s wit and her performances constitute a rebellion against Ballen’s [George Macready] and Johnny’s narrow construction of her identity, a misogynist representation of women within the film that is not — as a result of Gilda’s power, intelligence, and invitation to sympathize with her — endorsed by the film.

“…Gilda’s charismatic performances, like her wit, disrupt male voice-over, narration, and control, substituting female autonomy for male ideation…

“Rita Hayworth’s famed ‘Put the Blame on Mame’ number contributed to Rita Hayworth’s status as a pin-up, which according to Maria Elena Buszek, reflected female agency in important ways. At the end of her chapter ‘New Frontiers: Sex, Women and World War II,’ Buszek says,

‘[t]he pin-up provided an outlet through which women might assert that their unconventional sexuality could coexist with conventional ideals of professionalism, patriotism, decency, and desireability — in other words suggesting that woman’s sexuality could be expressed as part of her whole being.’ [Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture, Duke University Press, 2006, 231]

“…Rita Hayworth’s image, like other pin-ups who were ‘neither domestic nor submissive (Buszek, 186), would eclipse Hayworth’s life and properly nuanced readings of Gilda, as a result of cultural obsessions with the ‘femme fatale’ figure.” (103-105)

Why the Woman in Distress Is Excluded from the Hardboiled Paradigm

For the DVD of The House on Telegraph Hill (Fox Film Noir, 2005), Eddie Muller provides the special feature commentary. Muller is the self-titled “Czar of Noir,” the author of books about film noir, such as Dark City (St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998), and the president of the Film Noir Foundation.

As the credits roll at the opening of the film, he says:

“The story you are about to see is a strange hybrid. This movie shows up in a lot of film noir directories, reference books, listed as a film noir because it does come at the crest of that original film noir movement in Hollywood. But, in fact, it actually belongs more to the woman in jeopardy genre. It’s not quite as well-known or as successful as some of its antecedents, like Rebecca, Dark Waters, Gaslight, Suspicion.”

Much later in his commentary, he says, “At this point you can clearly identify this, like I said before, as a woman in jeopardy film, more so I think than a true film noir.”

Muller says The House on Telegraph Hill “shows up in a lot of film noir directories, reference books.” He contends it is “listed as a film noir” in these books “because it does come at the crest of that original film noir movement in Hollywood.” That is, according to Muller, the reason the film is included in these books is because of the timing of its release (1951).

Furthermore, he doesn’t explain why it isn’t “a true film noir.” He simply states his opinion and leaves it at that.

For readers of Muller’s Dark City, it is predictable that he wouldn’t consider The House on Telegraph Hill as “a true film noir.”

For readers of Muller’s Dark City, it is predictable that he wouldn’t consider The House on Telegraph Hill as “a true film noir.”

• The film isn’t cited in the book’s index.

• None of the chapters address a character like the woman in distress (or even mention Muller’s term on the DVD, “woman in jeopardy”).

• The only chapter that focuses on women in film noir is called, “Vixenville.” The films highlighted in this chapter, as one would assume from its title, feature a femme fatale.

In his commentary for The House on Telegraph Hill, Muller doesn’t discuss the mise-en-scène in the film, such as expressionist camera angles or chiaroscuro lighting. He doesn’t relate the film’s visual style – its noir visual style – with other films he considers “true film noir.”

Given Muller’s undefended opinion of The House on Telegraph Hill, along with the selective material in his Dark City, I infer that Muller’s rejection of it as “a true film noir” is based on his conception of what film noir is.

Recall what Muller says twice about The House on Telegraph Hill: it is “a woman in jeopardy film.” The implication must be, for that reason alone (since no he gives no other reason), it cannot be “a true film noir.”

Muller’s disagreement with the film noir historians who have compiled large filmographies is based on his being an exponent of the film noir hardboiled paradigm. Dark City is an exemplary representation of film noir according to the hardboiled paradigm. The House on Telegraph Hill isn’t hardboiled. Consequently, Muller cannot consider it as “a true film noir” by definition.

It is irrelevant to Muller that The House on Telegraph Hill shares affinities of visual style with other film noirs (a fact that he doesn’t mention). Michael Keaney, in Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), names three “noir themes” in the film: woman in jeopardy, greed and betrayal. Whatever the merits of the latter two noir themes, for Muller the first is a deal-breaker.

Ironically, Dark City is subtitled, “The Lost World of Film Noir,” because lost to Muller’s restricted hardboiled world is one of the most significant characters in “true” film noir, the woman in distress. She appears in film noirs more often than other characters that his chapters showcase. (For example, see Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale for a marked contrast in the number of film noirs with women in distress as opposed to those with femme fatales, who are, Muller says, “goddesses” in his “Vixenville.”)

Of course, Muller’s use of the term “woman in jeopardy” is demonstrably inaccurate. Take his own examples: Rebecca, Dark Waters, Gaslight, and Suspicion. In Rebecca and Gaslight, as I have shown above, a woman’s plight is psychologically based. Therefore, she cannot be, according to the dictionary definition, in jeopardy. In Suspicion, a woman thinks her life is in danger, but she is mistaken. In Dark Waters, at first conspirators try to frighten a woman (psychological plight). When she doesn’t scare, they physically endanger her. The term “distress” covers her situation for entire film, whereas “jeopardy” (or “peril”) only pertains to the latter section of the plot.

The House on Telegraph Hill is discussed as a canonical film noir, for reasons not considered by Eddie Muller, in the commentary by Robert Porfirio in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia.

“The House on Telegraph Hill finds itself in the film noir canon primarily because of the atmospheric photography of Lucien Ballard and the mannered use of authentic locales that enhances the immediacy of a threatening milieu. Furthermore, there is romantic narration by Valentina Cortese telling Victoria’s story in flashback, the devious characterization of Alan Spender by Richard Basehart, and the glacial performance of Fay Baker as the governess, Margaret. These elements together with hints of sexual aberration, the intrusion of an enigmatic past, the isolation and ultimate entrapment of the heroine in the old mansion all exploit certain conventions of noir period films like Gaslight and The Spiral Staircase. Like these earlier films, The House on Telegraph Hill has a climactic scene revealing that the victim’s peril is not imaginary – specifically where Alan and Victoria confront each other in the child’s playhouse and it appears momentarily that Alan is going to let his wife fall through a hole in the wall and down the steep embankment. The shooting and staging of this scene make it much more direct and menacing than similar confrontations in Suspicion and Phantom Lady.” (141)

For my analysis of one of the above four films, also published in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia, which discusses the hardboiled paradigm’s rejection of the woman in distress, see The Spiral Staircase.

For my public introduction to a film noir shown at the University of California, Berkeley, in which I underscore the significance of the woman in distress, see The Unfaithful.

For my in-depth critique of the hardboiled paradigm’s rejection of the woman in distress, see Repeat Performance vs. Hardboiled.

Addendum: A book that references “Woman-In-Distress Noirs”

Regarding the woman in distress, there is an exception to the statement in the first paragraph of this page that “no attention had been paid to this paramount film noir character.” The first chapter of Paul Duncan’s Film Noir: Films of Trust And Betrayal (Pocket Essentials, revised and updated 2003) has the same title as that of the book, and its first section is “Definition.” Duncan opens with the typically inaccurate description of the two leading female characters in film noir. (For background on this inaccuracy, see “III. Greater Gender Equality” in the section “Three Key Aspects of Spy Noir,” and footnote 18, in the page Spy Noirs and the Origins of Film Noir.)

“The usual relationship in a Film Noir is that the male character (private eye, cop, journalist, government agent, war veteran, criminal, lowlife) has a choice between two women: the beautiful and the dutiful. The dutiful woman is pretty, reliable, always there for him, in love with him, responsible – all the things any real man would dream about. The beautiful woman is the femme fatale, who is gorgeous, unreliable, never there for him, not in love with him, irresponsible – all the things a man needs to get him excited about a woman. The Film Noir follows our hero as he makes his choice, or his choice is made for him.” (7)

“The usual relationship in a Film Noir is that the male character (private eye, cop, journalist, government agent, war veteran, criminal, lowlife) has a choice between two women: the beautiful and the dutiful. The dutiful woman is pretty, reliable, always there for him, in love with him, responsible – all the things any real man would dream about. The beautiful woman is the femme fatale, who is gorgeous, unreliable, never there for him, not in love with him, irresponsible – all the things a man needs to get him excited about a woman. The Film Noir follows our hero as he makes his choice, or his choice is made for him.” (7)

Duncan continues, “The Film Noir follows a number of discernible frameworks within which the characters clash and collide.” (8) These are, in the sequence he presents them, Documentary Noir, Heist Noir, Amnesia Noir, Nightmare Noir, Doppelgänger Noir, Gangster Noir, Psycho Noir, Psychological Noir, Runaway Noir, Gothic Noir, Victorian Noir, and Woman-In-Distress Noir. The last “framework” receives the least text.

“[I]n many Film Noirs, the woman remained in danger. Suspicion (1941) was one of the first and best of the Woman-In-Distress Noirs, which included Experiment Perilous (1944), Gaslight (1944, a man tries to drive his wife mad), and the classic My Name Is Julia Ross (1945).” (10)

After this one instance, Duncan never again in the rest of his book refers to Woman-In-Distress Noir. In the third and last section of his first chapter, he discusses seven film noirs “in depth.” In his review of Double Indemnity (1944), he calls Barbara Stanwyck’s character a “domineering femme fatale.” (25) However, he doesn’t say either Teresa Wright’s character in Shadow of a Doubt (1943) much less Kim Novak’s in Vertigo (1958) is a woman in distress. Furthermore, none of his four examples of a Woman-In-Distress Noir is identified this way in his filmography of “647 Film Noirs from the classic period (1940-1960).” Suspicion isn’t assigned any noir type; Experiment Perilous is Gothic Noir; Gaslight is Victorian Noir; and My Name Is Julia Ross is Nightmare Noir.

Duncan doesn’t distinguish between physical and psychological threats to a woman. As I have explained above, his use of distress (instead of jeopardy or peril) is correct. Fittingly, it so happens, two of his four examples correspond with one kind of threat and two with the other: psychological (Suspicion, Gaslight) and physical (Experiment Perilous, My Name Is Julia Ross).

Unlike his extended treatment of the femme fatale (7-8), Duncan limits his remarks about the woman in distress to the two sentences quoted above. The reason must be that he doesn’t acknowledge the significance (or the frequency of appearance) of the woman in distress. (For a demonstration that film noirs in the classic era, 1940-1959, have far more women in distress than femme fatales, see the page Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale.)

Duncan also doesn’t recognize that women in film noir are more than mere “choices” for men. It is, therefore, unsurprising that he makes an extremely poor decision to associate men with seven different character types (private eye, cop, etc.), while only citing two kinds of women (beautiful, dutiful). Although he mentions “Woman-In-Distress Noirs,” the first two sections of his first chapter, “Definition” and “History,” simply recapitulate familiar tenets of the film noir hardboiled paradigm – tenets that are challenged and debunked throughout the pages of The Film Noir File.

In the page The Film Noir Private Eye: Debunking the Myth, the first sentence is, “Of all the tenets of the film noir hardboiled paradigm, none is more deserving of debunking — none is more invalid — than the contention that the private detective is a film noir character prototype, an iconic character in film noir.” As quoted above from his “Definition” section, Duncan’s initial character type that he associates with men is the “private eye.” Clearly, Duncan begins with the PI because he believes this is the most recognizable if not important male character type in film noir. For a refutation of the significance of the private detective in film noir, see the page The Missing PI in Film Noir, and for a historical explanation of the undeserved elevation of the PI in film noir literature, see the page The Film Noir PI: Made in the ’70s.

Next, take two examples from his “History” section, which exactly conform to this paradigm.

First, Duncan gives the typical background story about where the film-makers of film noir came from.

“Many film directors and their creative personnel escaped Hitler’s Germany and hotfooted it to Hollywood. These included Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak, Fred Zimmermann and Edgar G. Ulmer. What is not generally acknowledged is that most came via France…German film-makers who visited Paris before heading for Hollywood include Robert Siodmak, Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Max Ophüls, Jacques Tourneur [sic; he was not German but French] and Curtis Bernhardt. Some French directors soon followed (Jean Renoir, Julien Duvivier, Jacques Tourneur [sic]). And there is one well-known British director, who served his film apprenticeship program in Berlin, who made his way to the City of Angels in 1939: Alfred Hitchcock. (12)

For a refutation that the noir visual style was imported from Germany and France to Hollywood, see the pages under What Explains the Visual Style of Film Noir? And in the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir, see the section Spy Noirs Refute Claims that the Noir Style Is Derived from European Émigrés and the following section What Explains the Noir Style in the Origins of Film Noir?

Second, Duncan makes the usual claim about what was the source material for film noirs.

“With the European and American directors in Hollywood, what were they to film? Hollywood primarily films the best-selling books of its time and in the late 1930s and early 1940s these were Hard-Boiled novels by the likes of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. This was a macho fiction where tough guys passed moral judgment on an immoral society. As the 1940s progressed, Noir Fiction by James M. Cain, David Goodis and Cornell Woolrich emerged. These were about the weak-minded, the losers, the bottom-feeders, the obsessives, the compulsives and the psychopaths. Noir shows these people sliding down into the abyss or, if they happen to be in it already, forever writhing, aware of the present pain, aware of the future pain to come.” (13)

For more discussion about the woman in distress, see the page Hollywood Heroines.

For a refutation that hardboiled crime fiction is the essential basis for film noirs, see the pages Published Sources: Women’s Noirs and Published Sources: Men’s Noirs, as well as the section Spy Noirs Refute Claims that Film Noir Is Derived from Hardboiled Crime Fiction in the page Spy Noirs and the Origins of Film Noir.