The Film Noir PI: Made in the ’70s

Introduction

Since the rise of film noir studies in the 1970s, journalists and academics have referred to the private detective as one of the icons and character prototypes of the classic period. (Originally, this time frame began in the early 1940s and ended in the late 1950s, e.g., 1940-1959. In the 21st. century there has been a growing acceptance that the classic period is from the late 1930s to the mid-1960s.)

The association of the private eye with film noir originates in the related association of hardboiled crime fiction with film noir.

A typical example is the page about film noir on Wikipedia, which says in the first paragaph:

“Many of the prototypical stories and much of the attitude of classic noir derive from the hardboiled school of crime fiction that emerged in the United States during the Great depression…Film noir encompasses a range of plots: the central figure may be a private eye….”

In the Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2010), under the definition, “Private Eyes,” Andrew Spicer says:

“With his belted trench coat, fedora, and dangling cigarette, the private eye is one of the most recognizable male characters in film noir.” (246)

In fact, however, the private investigator (PI) is rarely “the central figure” in any film noir.

Given the frequency of the assertion that the private detective is one of the most significant characters in film noir, its fallacy makes the assertion perhaps the most egregious error of the film noir hardboiled paradigm.

Other pages on this website that debunk the “common wisdom” that the PI deserves iconic status in film noir are:

The Not Hardboiled PI in Film Noir

Presentation

How can the private eye be such a recognizable character in film noir? For the same reason that the woman in distress is so invisible. The establishment of the film noir hardboiled paradigm has elevated the private detective to iconic status. Conversely, because the literature of film noir, academic and popular, has ignored the woman in distress, she is, literally and figuratively, unrecognized. And her status of being unrecognized is despite the fact that a woman in distress is “the central figure” in a plot more often than perhaps any other noir character. (For my explanation of this key character in US film noir, see the page Significance of the Woman in Distress. For my table that demonstrates the much greater frequency in US film noir of the woman in distress compared to the femme fatale, see the page Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale.)

In the The Private Eye: Detectives in Movies (Reaktion Books, 2013), Bran Nicol recognizes the role of film noir studies in creating an academic as well as public perception of film noir.

In the The Private Eye: Detectives in Movies (Reaktion Books, 2013), Bran Nicol recognizes the role of film noir studies in creating an academic as well as public perception of film noir.

“Film noir, more than other genres (such as the Western, for example), was a critical construction; a category imposed onto a body of films by later critics rather than a set of conventions 1940s film-makers consciously adhered to.” (48-49)

Nicol is also aware of the infrequency of the private eye in film noir.

“The tough private detective is undoubtedly one of the classic topoi of film noir…Surprisingly, however, this status results from only a relatively small number of examples in the classic film noir canon…The private eye may be ubiquitous in studies of film noir but he is comparatively rare on screen.” (33)

The rarity of the PI in film noir has been noted a couple of times before. In my essay , “The Rise and Fall of the War Noir” (Film Noir Reader 4: The Crucial Films and Themes, Limelight Editions, 2004), I say:

“The private detective, of course, has achieved status as a film noir icon. Yet it is actually rare for a hardboiled dick to be a central character. He may rule in a few renowned movies, but the two superpowers of film noir are civilians and cops….” (213.)

Since the publication of that essay, which focuses on my explanation of the plot elements and historical context pertaining to a critical set of US film noirs, released during WWII, which I call “war noirs,” I have significantly updated the text on my website. The post now includes many other war noirs that I have discovered, which are both spy noirs as well as crime noirs. (Regarding war noirs, see the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar. Regarding spy noirs, see the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US.)

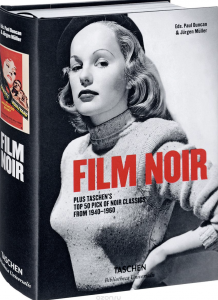

In the first quotation below, film noir historians Alain Silver and Jim Ursini also assert my opinion in their chapter, “The Private Eye,” in Film Noir, which they co-edited with Paul Duncan (Taschen, 2004). However, as we see in the second quotation below, despite their acknowledgment of the minor presence of the PI in film noir, their chapter begins as follows:

“The noir cycle may give the impression that many of its heroes were private investigators. In fact, aside from the pictures adapted from the novels of Chandler and Hammett there are very few.” (152)

“The noir cycle may give the impression that many of its heroes were private investigators. In fact, aside from the pictures adapted from the novels of Chandler and Hammett there are very few.” (152)

“If The Maltese Falcon is the consensus starting point for the classic period, then the private eye is an icon of film noir from the first moment. Whatever he was called – gumshoe, peeper, private dick, op, snooper, or shamus – the prototype for the noir character came out of the hard-boiled school of crime stories…from the early 1920s onwards….” (147)

Silver and Ursini’s chapter is reprinted in Film Noir, editors Paul Duncan and Jürgen Müller (Taschen, 2018, where the above quotations appear on pages 178 and 173, respectively). However, elsewhere in this massive anthology there is a very different view about the extent of the gumshoe’s involvement during film noir’s “classic era.” Burkard Röwekamp’s write-up of The Maltese Falcon includes a sidebar, “Private Eyes,” where he says:

Silver and Ursini’s chapter is reprinted in Film Noir, editors Paul Duncan and Jürgen Müller (Taschen, 2018, where the above quotations appear on pages 178 and 173, respectively). However, elsewhere in this massive anthology there is a very different view about the extent of the gumshoe’s involvement during film noir’s “classic era.” Burkard Röwekamp’s write-up of The Maltese Falcon includes a sidebar, “Private Eyes,” where he says:

“Much of the film noir of the 1940s and 1950s centers around the P.I., a jaded pessimistic outsider whose inquiries regarding seemingly cut-and-dry cases frequently unearth the schemes of a mastermind. And more often than not, a gorgeous woman with a dark past is wrapped up in the whole affair.” (237)

The ascendance of the PI to iconic status results from, to paraphrase Bran Nicol, “a critical construction…by later critics.” (48-49) The earliest writers about film noir, who were French, didn’t treat the private detective as a special, exalted character or as “one of the classic topoi.” Instead, they subsumed the private detective into larger categories. Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton, the authors of the first extensive study of film noir, A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941-1953 (City Lights Books, 2002; originally in Les Editions de Minuit, 1955), indicate how the private eye was early analyzed in terms of film noir.

“Nino Frank, one of the first to speak of ‘film noir,’ who subsequently managed to diagnose some of the basic traits of the series, nevertheless wrote, apropos of The Maltese Falcon and Murder, My Sweet: ‘[These movies] belong to what used to be known as the detective genre, and that from now on we’d better to call ‘crime adventure stories’ or, better still, ‘criminal psychology.’” (1)

Frank’s observation is provided in Film Noir Reader 2 (Limelight Editions, 1999, 15), where his essay is printed in full (originally published in L’Écran Français, August 1946). He isn’t enthralled with the private detective film. He finds The Maltese Falcon and Murder, My Sweet inferior to Double Indemnity and Laura.

The point Borde and Chaumeton are making is that Frank, despite identifying and naming “film noir” immediately after WWII, lacked the “necessary distance” in historical time to see The Maltese Falcon and Murder, My Sweet as themselves film noir. What is significant about this is that Borde and Chaumeton, writing in the early 1950s, also take private eye film noirs and categorize them as something else. At the end of their book they sub-divide the “major titles post-1940.” Their categories are: Film noirs, Criminal psychology, Crime films in period costume, Gangsters, Police documentaries, and Social tendencies. In contrast to modern writers who often devote a chapter in their books to the private eye, Borde and Chaumeton place their PI movies (The Maltese Falcon, Murder, My Sweet, Lady in the Lake, The Big Sleep, and Out of the Past) in the “Film noirs” category, where they are joined by 17 other titles. (161)

Borde and Chaumeton also deal with the private eye film noir in another way that is different from later authors. (Eddie Muller is an exception, as I note below.) Seemingly without realizing it, Borde and Chaumeton periodize the private eye film noir. The Maltese Falcon, for them, initiates film noir in 1941. (33-34) However, after they comment on The Big Sleep, Lady in the Lake and The Dark Corner – all from 1946 – they never again mention the detective in the remainder of their book. Their discussion of these three films is in the chapter, “The Glory Days (1946-1948).”

In an earlier chapter, “Toward a definition of film noir,” they say:

“It’s no accident, then, if scriptwriters have frequently had recourse to the character of the private detective. Casting too many aspersions on the official U.S police force was a ticklish problem. The private detective, midway between order and crime, running with the hare and hunting with the hounds, not overly scrupulous and responsible for himself alone, satisfied both the exigencies of morality and those of the criminal adventure story.” (7)

Although they assess how, in their view, film noir “comes to an end” in a chapter, “Decadence and transformation (1949-1950),” Borde and Chaumeton don’t explain why they only find the private eye in film noir for fewer than half of the years they cover in their book. On the one hand, they treat the private detective ahistorically when they attempt a “definition of film noir.” On the other hand, in their history of film noir, the lifespan of the PI is so brief that it doesn’t go beyond the first year of their so-called “glory days.”

Claude Chabrol, in an essay, “The Evolution of the Crime Film,” periodizes film noir, and not, as do Borde and Chaumeton, the private eye in film noir (Film Noir Reader 2; originally in Cahiers du Cinéma, #54, 1955).

“Then an abrupt rediscovery of Dashiell Hammett, the appearance of the first Chandlers and favorable social atmosphere suddenly gave the hard-boiled genre acclaimed status and opened the doors of the studios to receive it. The popularity of these films from Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra and Huston’s Maltese Falcon continued to grow until 1948…As fate would have it, this movement carried within itself the seeds of its own destruction. Based on shocking and surprising the viewer, it could offer even the most imaginative of screenwriters and the most diligent directors, a limited number of dramatic situations, which after a few repetitions, could no longer achieve either shock or surprise.” (27-28)

It isn’t only the private eye film noir, like The Big Sleep, that Chabrol associates with “a rich vein” that later shows its exhaustion with a “sterile and flaccid knock-off” like Lady in the Lake. Instead, he sees the postwar crime film, in general, “trapped in a generic prison of its own construction” and only able “to hit its head against a wall like a frenzied fool.” Among the film noirs he cites disapprovingly are Ivy and The Crooked Way. (27, 29)

Chabrol claims that the resurgence of interesting crime films occurs when filmmakers treat the “crime theme [as] a pretext or a means but, in any case, not an objective.” His examples include: Lady from Shanghai, On Dangerous Ground, In a Lonely Place, Where the Sidewalk Ends, and Whirlpool.

From the 1970s onward, the 1940s private eye is accorded iconic status. Chabrol, writing in the 1950s, disparagingly connects the hardboiled PI with the gentleman detective of the 1930s! He says, “Whatever it may be, spanning successes and failures, this evolution is undeniable; and no one, I think, would pine for The Thin Man or Murder, My Sweet of yesteryear while watching today’s In a Lonely Place or The Prowler.” (30, 32)

Bran Nicol apparently wants to have his cake as well as eat it. First, he notes that that the iconic status of the private detective “results from only a relatively small number of examples in the classic film noir canon.” (38) Later, he says, “the noir detective movie [is] a significant enough minority within the overall noir canon to alter our thoughts about it (and [is] widely credited as the original form of film noir).” (112)

Nicol’s source for the private eye film noir being “the original form of film noir” is Thomas Schatz’s Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking and the Studio System (Random House, 1981). Although Nicol provides no page reference in Schatz’s book, he is probably referring to one of the subsections about film noir in the chapter, “The Hardboiled-Detective Film.”

Hollywood Genres was published after the rise of film noir studies, which established the private eye as an icon, a classic topoi, etc. Therefore, I don’t consider Schatz’s book as a meaningful source for Nicol’s assertion that the private eye film noir is the original form of film noir. On the contrary, my essay in Film Noir Reader 4, “The Rise and Fall of the War Noir,” demonstrates that it isn’t true. For example, the key, recurring plot elements in film noir during WWII don’t include the private detective. (For an updated version of the original essay, see the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar.)

My contention is that the private eye’s “iconic” status is dependent on the “critical construction” of film noir during the rise of film noir studies in the 1970s. Furthermore, the PI’s status is part and parcel of the establishment of the hardboiled paradigm, which resulted from the “critical construction” of film noir.

Consider Charles Higham and Joel Greenberg’s Hollywood and the Forties (A.S. Barnes, 1968). It has the first discussion of film noir in English and was published prior to the rise of film noir studies. Chapter Two, “Black Cinema,” begins as follows:

“A dark street in the early morning hours, splashed with a sudden downpour. Lamps form haloes in the murk. In a walk-up room, filled with the intermittent flashing of a neon sign from across the street, a man is waiting to murder or be murdered…the specific ambience of film noir, a world of darkness and violence, with a central figure whose motives are usually greed, lust and ambition, whose world is filled with fear, reached its fullest realization in the Forties. A genre deeply rooted in the nineteenth century’s vein of grim romanticism….” (19-20)

After the mid to late 1970s, any reader of their book, being already familiar with film noir, would find their description of it rather conventional. However, that reader would probably be perplexed by their claim that film noir is “deeply rooted” in nineteenth century romanticism. Furthermore, he or she would probably be confused that the chapter, “Black Cinema,” doesn’t mention the private eye. Then, it would compound that reader’s befuddlement to find the discussion of the private detective at the beginning of a different chapter, “Melodrama.”

“A wry detachment, an amused view of the subject: these are the qualities of the best Forties melodramas. The films were made by hard-bitten men who knew city life inside out: they have the flavor of a neat Scotch-on-the-rocks. And of all the figures who walked through their half-world, Humphrey Bogart justly remains the most durable.” (39)

Higham and Greenberg immediately move on to discuss the film versions of Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, The High Window (i.e., The Brasher Doubloon), Lady in the Lake, and Farewell, My Lovely (i.e, Murder, My Sweet). Many other films now considered film noir are included in their chapter on melodrama.

Why would this reader find Higham and Greenberg’s analysis so unexpected? Because the reader would have been, as it were, indoctrinated by the tenets of the film noir hardboiled paradigm. For example, the reader would associate the literary background of film noir with hardboiled crime fiction. However, this isn’t the relationship that Higham and Greenberg make. (For my discussion of the literary roots of film noir, see the page Hardboiled Sentimentality.)

Furthermore, the reader’s belief that the literary background of film noir is to be found in the stories and novels of Hammett and Chandler would lead the reader to expect reference to the significance of the private eye in film noir. Higham and Greenberg don’t provide this.

The issue isn’t that Higham and Greenberg’s analysis is inaccurate. Their distinctive approach must be put in historical context. They describe film noir without addressing its hardboiled literary roots and its iconic private eye because they researched, wrote and published before the rise of film noir studies, before the establishment of the film noir hardboiled paradigm.

Before looking at the next, and the last, book that deals with “film noir” (without using the term) published prior to the rise of film noir studies, I want to review one example of the film noir hardboiled paradigm’s presentation of the private eye. In his Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir (St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998), Eddie Muller has a chapter, “Shamus Flats.” He says:

“Somewhere in the mid-Forties, the lonesome rider on the range passed the iron to a new icon of macho American independence – another cynical, alienated, yet incorruptible lone wolf: the private detective. Here was a guy without roots who knew all the ins and outs of Dark City.” (68)

Predictably, Muller immediately shifts his focus from the PI character to his hardboiled literary roots, which are described in detail. A couple of pages later, he gets to his first discussion of a private eye film noir, The Maltese Falcon. Noting that in the film, “[t]he question of ‘Who done it?’ is moot,” he adds:

“Most detective stories that emerged from Dark City followed this pattern. They had less to do with intricate plots and feats of deduction than they did with the tarnished chivalry and jaundiced attitude of the detective.” (73)

Muller continues with expositions of Raymond Chandler, as an author, and the private eye film noirs made from his books. He adds stories about producers, directors and actors, such as, “When Bogart wasn’t backchatting Bacall, he made time with various women who went into heat at the sight of him.” (75)

Like Borde and Chaumeton, Muller begins by ahistorically assigning the private eye profound importance (in the mid-Forties, the iron is passed from the cowboy to “a new icon of macho American independence,” the private detective). And also like them – except with self-consciousness – Muller acknowledges that the time of the private eye doesn’t last past the mid-Forties. “It had only been five years since John Huston put the first true hard-boiled dick onscreen, but The Dark Corner played like it was directed by Madame Tussard. There would be one blast of transcendence, however, before the shamus passed into self-parody.” (76) That transcendent private eye film noir is Out of the Past.

In Eddie Muller’s discussion of the private detective, and the chapter in his book is representative of the hardboiled paradigm, the significance of the PI to film noir is a given. Accordingly, not much analysis of what the private eye means in these films is presented. An observation here and there, but nothing sustained.

“[I]t was the reflective nature of the detective’s first-person narration, weary with regret and resignation, that made these stories you could take personally. This is the essential distinction between the noir detective and other fictional sleuths. He may solve a case, but the answer to the big mystery, what he’s really after, always eludes him.” (74)

In 1969, the year between the publication of Higham and Greenberg’s Hollywood and the Forties and the coming of film noir studies, Barbara Deming’s Running Away from Myself: A dream portrait of America drawn from the films of the forties finally became a book, from Grossman Publishers. Her original, unpublished longer version was completed in 1950, and it was entitled, A Long Way from Home: Some Film Nightmares of the Forties.

As the film analyst for the Library of Congress, Barbara Deming saw a quarter of all Hollywood feature films from 1942 to 1944. Although she saw fewer from 1945 to 1948, she “carefully selected” those that she did see “with a view to missing no new trends.” For each film she “took lengthy notes in shorthand – a very literal moment by moment transcription.” (6, footnote)

Deming was similar to French critics, such as Nino Frank, who saw a wave of American films after WWII and discerned common themes and moods, which became the basis for the term film noir. However, unlike the French, Deming didn’t merely view a sampling of Hollywood product in a relatively concentrated timeframe. She analyzed thousands of films during the war and on into the late Forties. She finished her original book a few years before Borde and Chaumeton published theirs. Her recognition that Hollywood released “film nightmares in the Forties” places her among the earliest, as well as most incisive, historians of film noir. (See Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward, editors, Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style, The Overlook Press, Third Edition, 1992, 373)

Deming begins the chapter, “I’m still alive! (tough boy),” as follows:

“There is one hero, featured in many films of these years, who is set down in a world more frankly nightmare than any I have yet reported – a world bristling with dangers, where no voice is to be trusted and the seductive treacherous female truly reigns, death lurks more surely in the center of the embrace. This hero is the familiar ‘tough boy’ hero of thrillers derived from Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and their like. He is usually a ‘private eye,’ hired to perform some apparently routine job, to locate missing person or missing heirloom, but involved before the tale is out in matters more unusual.” (140)

So far this may seem like a quote from an author associated with the film noir hardboiled paradigm. But that paradigm hadn’t yet been established, and the private eye hadn’t yet been deemed iconic. Deming’s treatment of the PI is quite different. In contrast to Eddie Muller, who claims the detective “knew all the ins and outs of Dark City,” Deming says:

“[O]ne can wonder at moments just how many brains this hero has, himself…If one sets film next to film, if one sets, even, incident next to incident in any one film in this series, the roughings-up, the workings over this hero endures assume very nearly comic proportions.” (142)

Deming doesn’t see the private eye as Muller describes him, “a new icon of macho American independence – another cynical, alienated, yet incorruptible lone wolf.” Instead, she wants to know why the following happens:

“Again and again the scene recurs in which, blackjacked, doped, punched in the kidneys, kicked in the temples, he blacks out; and again and again he drags himself to his feet, studies his battered self in the mirror, and then, face set, returns for more.” (142)

Deming knows that the PI doesn’t take these beatings for the money, because he could make more by letting someone “sugar him off” the case. So she wonders why the private eye acts in a seemingly irrational way. With the coming of the hardboiled paradigm, an explanation about the PI’s motives eschewed evidence. Recall that Muller says the private eye is searching for “the answer to the big mystery, what he’s really after, [which] always eludes him.” In contrast, Deming looks for evidence to explain the PI’s behavior. She finds the answer to her question by closely analyzing a “series” of private eye films. Her conclusion is:

“[The] hero takes the hopeless case, enters the deadly embrace, to prove to himself that he can emerge intact….The assaults that he endures, and that he provokes, are various. On one level is sheer physical battering. The test is to get up onto his feet again after anything, shake himself, and go on his way. The test at another level is to avoid ever acting as another’s tool Even when it would not particularly hurt to, he must never let himself be turned simply to the client’s purpose…Film after film since The Maltese Falcon has put its hero through these same fires.” (152-154)

After all that is done to him, he can say, “I’m still alive!”

Deming’s “tough boy” is a survivor and has pride. There is little in common between him and Muller’s shamus who sports a “tarnished chivalry and jaundiced attitude.”

Shortly after the publication of Running Away from Myself, a new and different conception of the private eye and his relationship to film noir emerged in the film noir studies of the 1970s. He would be defined as “cynical, alienated.” In relation to film noir, the PI wouldn’t be a particular character, as Deming takes great pains to show. Instead, as proposed by Alain Silver and James Ursini (Film Noir, Taschen, 2004), he would be “the prototype for the noir character.” (187)

Addendum

An example of how film noir studies came about in the 1970s is shown by the frequency of copyright dates in the 1970s for the essays in Film Noir Reader (Limelight Editions, 1996). In the Acknowledgments, the editors, Alain Silver and James Ursini, say, “Our idea to publish a series of essays on film noir goes back to the fall of 1974.” They call these essays “seminal” and “classic.”

After excerpts from the books, cited above, by Borde and Chaumeton, and Higham and Greenberg, respectively, 11 of the following 14 essays were originally copyrighted between 1970 and 1979. (One of the remaining six essays was published in 1985, and the other five were published in the 1990s.)

More about the significance of the 1970s is provided in a historical essay, “Other Studies of Film Noir,” in the third edition of Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (The Overlook Press, 1992). At the beginning of the essay, the authors note that the first edition, published in 1978, “was the first comprehensive survey to appear in the English language….” (372)