The Not Hardboiled PI in Film Noir

Introduction

Bran Nicol, in The Private Eye: Detectives in the Movies (Reaktion Books, 2013), describes “two kinds of noir detective.”

“When it comes specifically to professional private eye protagonists in classic film noir there are two distinct kinds. The most iconic type is the intrepid, tough-guy detective drawn from the fiction of Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler. This is both the original noir private eye, setting in place conventions other films will follow – the wisecracking, the womanizing, the ability to access all the places of the city, both affluent and poor – and the character in its purest form, that is, a man who remains completely professional and independent.” (34)

“The Spade/Marlowe prototype is the most familiar kind of cinematic private eye. But there is also a second type of private detective in classic noir who, in a more understated way, is just as responsible for the cementing the figure in screen convention. This is the reluctant or disaffected private investigator, a man who has no alternative but to become a private eye…He is often a police detective who becomes transformed into a private eye because of what happens to him in the narrative. Because there is something personal about the investigation he is involved in, he is compelled to start working as a solitary investigator, cast adrift from the force which employs him. We find this kind of detective in movies such as Laura, The Dark Corner, The Narrow Margin, and The Big Heat.” (39-40)

“The Spade/Marlowe prototype is the most familiar kind of cinematic private eye. But there is also a second type of private detective in classic noir who, in a more understated way, is just as responsible for the cementing the figure in screen convention. This is the reluctant or disaffected private investigator, a man who has no alternative but to become a private eye…He is often a police detective who becomes transformed into a private eye because of what happens to him in the narrative. Because there is something personal about the investigation he is involved in, he is compelled to start working as a solitary investigator, cast adrift from the force which employs him. We find this kind of detective in movies such as Laura, The Dark Corner, The Narrow Margin, and The Big Heat.” (39-40)

“These two kinds of detective – self-employed ‘lone wolf,’ and disaffected policeman – are the figures who emerge from the first ‘wave’ of private eye films, part of classic noir in the 1940s and ‘50s. (40)”

(I cannot fathom why Nicol includes The Dark Corner, which features a professional private eye, as an example of his second type of noir detective.)

Presentation

The definition of Nicol’s second type of noir detective is very flawed. In classic noir, there are many men who find that they have “no alternative but to become a private eye,” but they aren’t policemen. For example, it happens to Ray Milland in Ministry of Fear, Tom Conway in Two O’Clock Courage and William Powell in Take One False Step. Their characters are at least as interesting and important – if not more so – than the Nicol’s disaffected policemen. The disaffected policeman is a secondary example of this type of noir detective. The primary example is the civilian private investigator. For example, during the Second World War, he is often a “hunted man.” (See the page The Hunted Man & the PI in WWII.) Furthermore, in these years the civilian private investigator isn’t necessarily a man. Instead, she is a woman who is trying to clear the name of a falsely accused (and hunted) man. (See the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar.)

Nicol’s first type is supposedly represented in the film noirs I have cited on the page The Missing PI in Film Noir. In each one there is a professional private eye, a lone wolf. However, in only some of them is he a “tough-guy detective.” In other words, in classic film noir there are two types of professional private eyes, one who is tough, and one who is not.

The film noir hardboiled paradigm fails to represent correctly what occurs in classic film noir. Its focus is on “the most iconic type” of PI, namely “the tough-guy detective.” However, in my list below, the detective isn’t a “tough-guy” in 17 out of 33 instances. He isn’t hardboiled. (The basis for the list is explained in the page The Missing PI in Film Noir.)

Eddie Muller sees 1947 as the end of the private eye film noir (Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir), whereas Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton date it a year earlier (Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941-1953). For more on their views, see the page The Film Noir PI: Made in the ‘70s.

Below is a list, in chronological order, of the 33 private eyes in film noirs during the “classic era” (which includes the two in The Dark Corner). Muller is correct that the heyday is over around 1947. Therefore, it is significant that, of the 24 private eyes in film noirs released through 1947, the central figure in 15 of them isn’t a hardboiled PI.

Although there are only six private eye film noirs in the Fifties, five of them have a hardboiled PI. The much higher percentage of private eye film noirs with a hardboiled dick isn’t simply because three of them feature Mike Hammer. There are, for example, four Phillip Marlowe film noirs in the mid-Forties, but in only two of them is he hardboiled.

What seems to have occurred is that there was an intentional choice not to use an actor who would be a tough-guy. Those responsible for hiring the actor didn’t want a wisecracker, a man who would be reminiscent of a hardboiled dick in a pulp magazine. If they had wanted to cast someone like Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon or Dick Powell in Murder, My Sweet, they would have selected actors accordingly – as well as had the scripts written differently.

What does it mean that the actors and the scripts didn’t conform more closely to the first private eye film noirs? The answer is surely that the film noir hardboiled paradigm fails to describe accurately the place of the PI in the film noir canon. To use Bran Nicol’s phrase, the “critical construction” of film noir in the Seventies turned the tough-guy private detective into an iconic character. However, the actual filmography of film noir doesn’t demonstrate that this status is true. (For more about this “construction,” see the page The Film Noir PI: Made in the ‘70s.)

The failure of the hardboiled paradigm’s interpretation of the PI requires a new, comprehensive re-appraisal of the private eye in film noir. His stature will be greatly diminished. However, as the status of the private detective is reduced, the status of other, more prevalent and important characters in film noir, such as the woman in distress and the hunted man, will be elevated. The rejection of a central tenet in the hardboiled paradigm will result in a better interpretation of film noir.

Private Eye Film Noirs with a Hardboiled PI (or not): title, date, private eye (actor), whether hardboiled or not hardboiled.

The Maltese Falcon, 1941, Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart), hardboiled

Grand Central Murder, 1942, “Rocky” Custer (Van Heflin), not hardboiled

Quiet Please, Murder, 1942, Hal McGuire (Richard Denning), not hardboiled

Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, 1942, Sherlock Holmes (Basil Rathbone), not hardboiled

Time to Kill, 1942, Michael Shayne (Lloyd Nolan), hardboiled

Murder, My Sweet, 1944, Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell), hardboiled

The Falcon in San Francisco, 1945, Tom Lawrence/”the Falcon” (Tom Conway), not hardboiled

The Spider, 1945, Chris Colton (Richard Conte), not hardboiled

The Tiger Woman, 1945, Jerry Devery (Kane Richmond), hardboiled

Accomplice, 1946, Simon Lash (Richard Arlen), not hardboiled

The Big Sleep, 1946, Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart), hardboiled

The Dark Corner, 1946, Bradford Galt (Mark Stevens), not hardboiled

The Dark Corner, 1946, Stauffer (William Bendix), hardboiled

The Last Crooked Mile, 1946, Tom Dwyer (Don Barry), hardboiled

Mysterious Intruder, 1946, Don Gale (Richard Dix), hardboiled

The Mysterious Mr. Valentine, 1946, Steve Morgan (William Henry), not hardboiled

Blackmail, 1947, Daniel J. Turner (William Marshall), not hardboiled

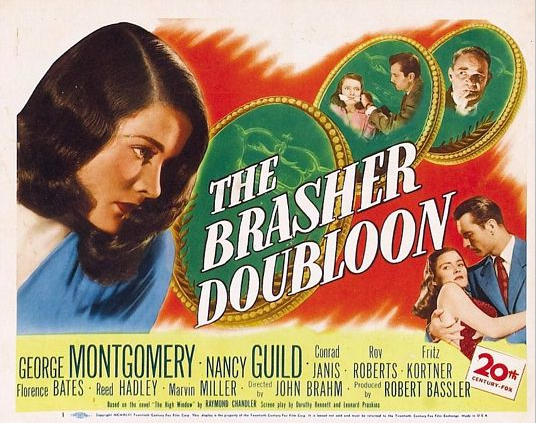

The Brasher Doubloon, 1947, Philip Marlowe (George Montgomery), not hardboiled

High Tide, 1947, Tim Slade (Don Castle), not hardboiled

Lady in the Lake, 1947, Phillip Marlowe (Robert Montgomery), not hardboiled

My Favorite Brunette, 1947, Ronnie Jackson (Bob Hope), not hardboiled

Out of the Past, 1947, Jeff Markham/Jeff Bailey (Robert Mitchum), hardboiled

Philo Vance’s Gamble, 1947, Philo Vance (Alan Curtis), not hardboiled

Riff-Raff, 1947, Dan Hammer (Pat O’Brien), not hardboiled

Behind Locked Doors, 1948, Ross Steward (Richard Carlson), not hardboiled

I Love Trouble, 1948, Stuart Bailey (Fanchot Tone), not hardboiled

Return of the Whistler, 1948, Gaylord Traynor (Richard Lane), not hardboiled

Guilty Bystander, 1950, Max Thursday (Zachary Scott), hardboiled

The Fat Man, 1951, Brad Runyan/”The Fat Man” (J. Scott Smart), not hardboiled

World for Ransom, 1954, Mike Callahan (Dan Duryea), hardboiled

I, the Jury, 1953, Mike Hammer (Bill Elliot), hardboiled

Kiss Me Deadly, 1955, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker), hardboiled

My Gun Is Quick, 1957, Mike Hammer (Robert Bray), hardboiled

Addendum

There are two private eyes in The Dark Corner, Bradford Galt (Mark Stevens) and Stauffer (William Bendix). Galt’s recently hired secretary, Kathleen (Lucille Ball), tells him right away that she is “playing for keeps,” i.e., for a wedding ring. Hardy Cathcart (Clifton Webb) is the client for both detectives. After Cathcart has Stauffer commit murder to frame Gault, Cathcart kills Stauffer.

Stauffer is a hardboiled PI. Galt, on the other hand, “is shown to be continually dependent upon Kathleen as a nurturing figure, as a woman who can raise his spirits and provide shelter from the turmoil of the masculine arena of crime and detection: from the regime of ‘masculine testing’ into which Cathcart machinations force him. Not only this, but she persistently criticizes Galt’s profession as a private eye, encouraging him to abandon the ‘tough’ masculine regime, and chastising him when he insists upon adopting a ‘tough’ masculine attitude (‘You’re afraid of emotion. You keep your heart in a steel safe’).” (Frank Krutnik, In a Lonely Street: Film noir, genre, masculinity, Routledge, 1991, 102-103)

Kathleen wears “the belted trench coat,” not Galt.

In the end of the film, Galt doesn’t “get” Cathcart. Instead, just before Cathcart can kill Galt, he is shot dead by his wife, Cathy (Mari Downs), out of revenge. Cathcart had Stauffer murder her lover, Anthony Jardine (Kurt Kreuger), and then frame Galt for the killing. The finale is marriage between Kathleen and Galt.

On the film’s poster Mark Stevens is identified as “the new tough guy.” It also says, “He’s Different — and Dangerous!” None of this is remotely true. Bradford Galt is the character that has been repeatedly – and quintessentially – quoted in academic and popular writing about film noir, “I feel all dead inside. I’m backed up in a dark corner, and I don’t know who’s hitting me.” Movie posters, of course, often misrepresent what occurs in the film itself. It is atypical, however, for a poster’s text to represent falsely a character’s attributes.

Despite what the poster claims, Bradford Galt is one more private eye who isn’t a tough guy. He isn’t hardboiled.