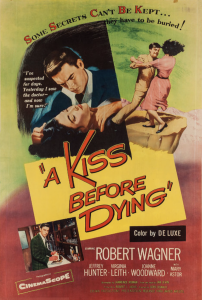

A Kiss Before Dying

Introduction

The text in the Presentation below is based on my plot summary and commentary about A Kiss Before Dying, as published in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia (Overlook Duckworth, 2010, 166-167). It has been reformatted into shorter paragraphs.

Afterwards, in an Addendum, I critique a key aspect of Robert Miklitsch’s analysis of A Kiss Before Dying, which is included in his book, The Red and the Black: American Film Noir in the 1950s (University of Illinois Press, 2017).

Main Credits

Director: Gerd Oswald. Screenplay: Lawrence Roman based on the novel A Kiss Before Dying by Ira Levin. Producer: Robert L. Jacks (Crown Productions). Director of Photography: Lucian Ballard. Music: Lionel Newman. Art Director: Addison Hehr. Editor: George Gittens [George A. Gittens]. Cast: Robert Wagner (Bud Corliss), Jeffrey Hunter (Gordon Grant), Virginia Leith (Ellen Kingship), Joanne Woodward (Dorothy [‘Dorie’] Kingship), Mary Astor (Mrs. Corliss), George Macready (Leo Kingship), Robert Quarry (Dwight Powell), Howard Petrie (Howard Chesser, Chief of Police), Bill Walker (Bill, the Butler), Molly McCart (Annabelle Koch), Marlene Felton (Medical Student). Released: United Artists, June 12, 1956. 94 minutes.

From Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

Plot Summary

Bud and Dorie are having a secret affair. With a legitimate marriage, he will fulfill his dream of becoming wealthy at her father’s copper mining company. However, she gets pregnant and doesn’t care that her father will disown her. Bud asks her to meet him at the marriage license bureau. He takes her to the building’s rooftop and pushes her off. He makes her death look like suicide. Next, he gets engaged to Ellen, Dorie’s sister. Ellen figures out Dorie thought she was going to marry someone, and it was that man who killed her. She tracks down Dwight, an ex-boyfriend of Dorie’s, and accuses him of the murder. He denies it. Dwight goes to his dorm room to get the address of Dorie’s next boyfriend. Bud, who has been following Ellen, is waiting there. He shoots Dwight, making it look like Dwight committed suicide in remorse for killing Dorie. Gordon, the police chief’s nephew and once Dorie’s tutor, discovers Dwight couldn’t have killed Dorie, so he would have had no reason kill himself. Evidence against Bud mounts. Desperate to avoid arrest, he tries to murder Ellen, but he is accidentally killed instead. Gordon has longed for Ellen since they met, but it is unclear what their future holds in store.

Commentary

Although A Kiss Before Dying recalls A Place in the Sun, a significant difference is that in A Place in the Sun there is no question that men love women (as mothers, girlfriends, wives, or daughters), whereas in A Kiss Before Dying a key question is whether Bud or Leo Kingship (Dorie and Ellen’s father) is capable of sincere affection for women.

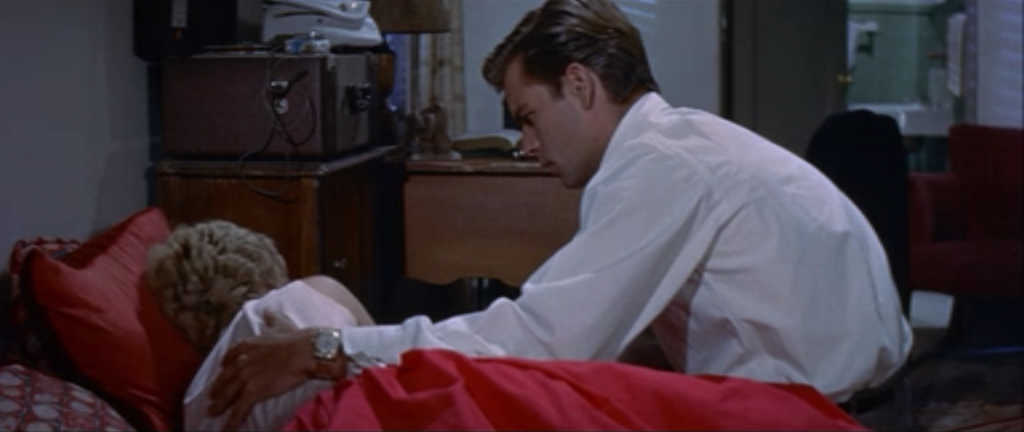

Unlike George Eastman in A Place in the Sun, Bud doesn’t have a benevolent rich uncle to help him get ahead. He only has will power, signified each time he hunches his shoulders (he will do whatever it takes, including murder) and by a framed newspaper article that says in school he was voted the most ambitious and the most likely to succeed. In the opening scene the camera pans through his bedroom until it is above Bud, who is looking down at the back of Dorie’s head. She isn’t important enough to be seen; she is only a means for him to get a place in the Kingship copper company.

Bud’s working-class mother embarrasses him. He recoils at her tastelessness in clothes and unsophisticated conversation. Although A Kiss Before Dying brims with bright colors – especially orange, yellow and light blue – Bud’s mother’s hair, Dorie’s sports car, Ellen’s swimming pool’s ladders, and her poolside telephone are the color of copper. Since this color associates each of these women with Bud’s goal, it objectifies them, reinforcing that they serve to help him realize his ambition.

Because Dorie is a means to an end, if Bud has to get rid of her, he will use Ellen instead. If Bud has to murder Ellen, too, then he will advance himself without marrying either of Leo’s daughters. (In Ira Levin’s novel, after Bud murders Dorie and Ellen, he tries to marry a third sister, Marion.) Just before Bud attacks Ellen, he tells her, “Your father and I will grieve together. We’ll have that to share between us.” However, Bud not only fails to kill Ellen, but also at the conclusion of the film he and Leo no longer share having a clump of ore where there should be a heart.

Bud may not change during the movie, but the transformation of Leo from a heartless to a sensitive father is central to the second half of the film. Dorie and Ellen disdain him because he divorced their mother, “sick and all,” after she’d made “one little slip.” Since the police believe Dorie committed suicide, Leo accepts Gordon’s advice not to look for the man she had been dating, to avoid stimulating “talk” about her death. Adding insult to injury in Ellen’s view, Leo refuses to take with him the “valuables” found in Dorie’s purse. He tells the police chief, “Dispose of them as you see fit.” Pained, Ellen looks at him and says, “But….” Leo continues,” I’d consider it a favor.” Leaving the police station, he reaches out to touch Ellen, but she moves away.

When Ellen gives reasons Dorie didn’t kill herself, Leo thinks she’s “distorting the facts,” and Gordon says her ideas are “far-fetched.” So she hunts the killer on her own.

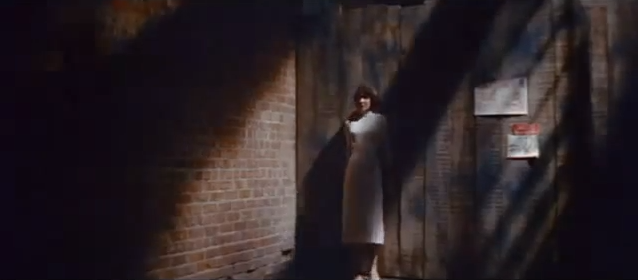

The night scene Ellen confronts Dwight shows the most noir style in the film. She is shot high overhead as she walks toward a bar and then crosses a wet street to an alley. There Ellen is framed close up against a brick wall, her head’s shadow looms behind her, and another shadow angles across her chest.

Presumably, the imagery presages her death because, if Dwight had killed Dorie and if he sees Ellen, then he will kill her, too. Dwight does see her, and he chases her to the end of the alley, where a huge diagonal shadow runs down the wall and over her entire body.

Dwight grabs her arms, as Bud later does when he tries to kill her. The noir style misleadingly suggests Ellen is in peril because, in fact, she fights back, shouting, “Let me go! Take your hands off me!”

Ellen’s resistance to Dwight is as strong as her insistence to Leo and Gordon that Dorie was murdered. When Ellen comes home, there is a volte-face in Leo’s behavior toward her. Although she won’t let him touch her, he shares her relief that Dorie didn’t commit suicide. “If you’re better, I’m fine,” he smiles.

After Ellen survives Bud’s attack, Leo approaches her but doesn’t touch her. She bumps into him as she walks past him. Neither says a word. They turn and face each other. Ellen puts her hand on Leo’s arm.

Completing their rapprochement, Leo gently holds her arm as Ellen step into his car. The finale isn’t about Ellen and Bud, or Ellen and Gordon. The conclusion of A Kiss Before Dying is that Leo at last has a heart and Ellen knows it.

Addendum: Robert Miklitsch’s Misinterpretation of Ellen Kingship

In his book, The Red and the Black: American Film Noir in the 1950s (University of Illinois Press, 2017), Robert Miklitsch has a chapter called, “Noir en couleur: Color and Widescreen,” which considers four films: Black Widow, House of Bamboo, Slightly Scarlet, and A Kiss Before Dying.

At the end of his discussion of A Kiss Before Dying, Miklitsch focuses on Ellen Kingship as being a “girl detective.” The term is used by the killer, Bud Corliss, in Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1953). In 1954, Levin won the Edgar Allen Poe (“Edgar”) Award from the Mystery Writers of America for the best first novel by an American author.

Miklitsch says, “In Levin’s novel, Bud refers to Ellen as the ‘girl detective,’ taunting her right before he shoots her: ‘No, you had to be the girl detective! Well, this is what happens to girl detectives!’” (192)

Miklitsch defines Ellen as a “rare type in ‘50s noir, a woman with a real nose for detection.” (195) Among his analyses of the use of color in the film, he brings out how pink is associated with Ellen as a sleuth.

“In the concluding, climatic sequence of A Kiss Before Dying…in a sartorial twist that speaks volumes (since it’s the first time in the film that Ellen reprises an outfit), she’s dressed in the same pink cotton dress she donned when she decided to act on her suspicion that her sister’s death was not a suicide…Though pink has traditionally been associated with femininity – with the accent on the word femme – it’s also a mixture of red and white, danger and purity. Ellen’s pink cotton dress therefore marks the moment in A Kiss Before Dying when she transitions from being a potential victim to a private eye. In Levin’s novel Ellen Kingship falls prey to the kiss of the spider-man and pays for it, like Dorie, with her life. However, in Gerd Oswald’s noir en couleur, it’s the “girl detective” Ellen – pretty in pink – who masters the man who would be king.” (194, 195)

In the film, there is no mention by anyone that Ellen is behaving like a detective. Although she initially makes important deductions – such as that Dorie went to the building, where she fell to her death, intending to get married – Miklitsch isn’t justified to claim Ellen has “a real nose for detection.” Why? Because it would mean Ellen consistently acts like a “private eye.” On the contrary, Ellen abandons her conviction that Dorie was murdered and, consequently, she stops her investigation. It isn’t until the very end of “the concluding, climatic sequence,” when Bud makes a grievous slip of the tongue, that she is compelled to acknowledge her fiancé’s crimes. I suggest the causes of Miklitsch’s misinterpretation of Ellen result from, first, his reliance on Bud’s characterization of Ellen in the book and, second, his ignoring what Ellen, as well as Gordon, actually do in the film. This misinterpretation necessarily extends to Miklitsch’s opinion about the symbolism of Ellen’s “pink [and white checked] cotton dress.”

In both the book and the film, the following takes place. After Ellen concludes that Dorie was going to get married, she goes to Dorie’s university to find out who her sister’s “boyfriend” was. Dwight Powell, a classmate of Dorie’s, is one of her suspects. At a cocktail lounge, Dwight says he had stopped seeing her because she was getting too serious about their relationship. (The one meaningful distinction between the book and the film is that in the latter Dwight asks Ellen why she called her sister, “Dorie.” He says, “I never heard anyone call her Dorie.” She replies, “Somebody did. She mentioned it in her letter.” This exchange may seem inconsequential, but Ellen’s comment becomes the crux of the film’s climax.) He says that at his home he has the address of the student who went out with Dorie after he did. Ellen and Dwight don’t know that Bud is nearby listening to them. Because he has previously learned where Dwight lives, he leaves the bar before they do. While Ellen waits downstairs, Dwight goes up to his bedroom, where Bud is hiding in a closet, wearing gloves and holding a pistol. Once Bud approaches Dwight, the plots of the book and film become markedly different.

In the book, Ellen hears a shot and when she goes into the bedroom, she finds Bud with the gun and Dwight dead on the floor. Bud makes up excuses about why he overheard Ellen and Dwight at the bar and why he was in the closet. He says he saw Dwight pick up the gun and assumed he was going to kill Ellen. He came out of the closet, jumped Dwight and the gun “went off.” (165) They leave the place, but while Bud is driving Ellen in a (stolen) car, she persistently says he should give himself up. She thinks the police will believe Bud’s story that he shot Dwight by accident. She wants to call her father so that he “can take care of lawyers and everything.” (169) She also raises objections to Bud’s certainties that Dwight murdered Dorie and was going to use the gun to kill her. Ellen keeps at it until she realizes Bud is “going the wrong way.” (171) The ride ends when Bud makes Ellen get out of the car and shoots her. (It isn’t until the penultimate chapter of the novel that we learn, since she was “holding up the purse in a futile shielding gesture,” [178] “the first bullet wasn’t enough.” [270])

Contrary to Miklitsche’s interpretation of this scene, it isn’t what Ellen says in the car that brings about her death. (192) Instead, after they leave Dwight’s corpse, Bud doesn’t drive Ellen back to her hotel, as she assumes he will. Why? Because he has already made up his mind to commit a third murder. Ellen’s fatal error was to ignore Bud’s insistence that she shouldn’t investigate who Dorie had been dating. Ira Levin writes:

“I told you not to come,” he said querulously. “I begged you to stay in Caldwell, didn’t I?” He glanced at her as though expecting a confirmation. “But no. No, you had to be the girl detective! Well this is what happens to girl detectives.” (176)

Ellen’s sleuthing obviously ends here (when she dies), about two-thirds of the way through the book. Significantly, she also stops being a “girl detective” at the same place in the plot in the film, which refutes Miklitsche’s interpretation of Ellen.

In the film, Bud has already used Dwight’s typewriter to compose a suicide note. Bud makes Dwight sit in front of it. Standing on Dwight’s right side, Bud happens to see a framed Spanish language newspaper article with a photograph of Dwight holding a tennis racquet in his left hand. Bud steps around to Dwight’s left side so that (off camera) after he shoots Dwight in the left temple, he can place the gun in Dwight’s dominant hand. Ellen hears the shot and comes upstairs, but Bud gets away unseen. Bud’s note makes it seem that Dwight’s motive for killing himself was his guilty conscience about murdering Dorie, compounded by Ellen’s suspicion of him. The local chief of police credits Ellen with being right that Dorie didn’t kill herself. “You did it all,” he compliments her, adding, “Case open again, closed again, but for good this time.”

After Dwight’s death, Ellen returns to the Kingship house. Miklitsch describes and interprets the scene as follows, “Although Ellen returns safely home in a chauffeured black limousine, the long cypress shadows on the gravel driveway outside her father’s house suggest that the case is not quite closed yet.” (193) Who is going realize the case is still open? Who is going to solve the case? Will it be Ellen? To be a “girl detective,” to be a “private eye,” when the opportunity presents itself, she has to acknowledge the case isn’t closed and, therefore, she has to keep investigating until she cracks it. This isn’t what happens in the film, which is why Miklitsch misinterprets Ellen.

In the book, during Ellen’s visit to Dorie’s university, Gordon Gant becomes one of her suspects because he fits the description Dorie gave of the student she was seeing. In Ellen’s hotel room, Gordon protests that he “didn’t even know [Dorie’s] name until her picture was in the papers.” Also, he comes across and reads a letter that Ellen is writing to Bud. (120-121) Near the end of the novel it is revealed how much he discerns from it, and how it leads him to expose Bud’s guilt.

In the film, Gordon Grant works part-time at the police station in the (fictional) state university town of Lupton, Arizona. His uncle is the same chief who compliments Ellen after Dwight’s death. Gordon casually knew Dorie because he tutored her in math. Like his uncle, he believes she committed suicide. Nonetheless, when Ellen is about to leave the station with Leo (as described above in the “Commentary”), he introduces himself, expresses his sympathy and says, “If there’s anything that I can do to be of assistance in any official way, why, please feel free to call on me.”

Months later, Ellen has reason to take Gordon up on his offer. She flies to Lupton to explain to him why she now believes that her sister didn’t kill herself. First, Dorie fell from the “municipal building,” which is where marriage licenses are issued. Second, what Dorie was wearing matched the traditional bridal rhyme, “something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.” (In this scene, Ellen wears a pink and white checked dress and, as noted by Miklitsch above, she acts like a “private eye.”) Initially, Gordon dismisses Ellen’s conjecture that Dorie didn’t commit suicide but, instead, was murdered. Yet he changes his mind and agrees to help her, but only after he returns from a brief trip. Since Ellen is impatient, she tries on her own to discover Dorie’s “boyfriend.” This leads to her meeting with Dwight.

On the one hand, in the book, Gordon becomes suspicious about Bud when he reads Ellen’s letter, which is shortly before she and Dwight get together. On the other hand, in the film, Gordon doesn’t investigate Dorie’s death as a murder until after Dwight dies.

Coincidently, Gordon goes to the Kingship house to talk with Ellen on the afternoon of her wedding engagement party. He tells her that, as he was helping his uncle wrap up Dwight’s case, he made “the usual inquires to fill out the record. And there was one interesting fact that just came straggling in. It seems that on the day your sister died, Dwight Powell was playing tennis in a tournament in Mexico City. Been there almost a week.”

If Miklitsch is correct that Ellen has “a nose for detection,” then it stands to reason she will be highly interested in Gordon’s revelation. Instead, her reaction is, “I don’t believe it.” Gordon replies, “Well, you’ll have to. His teammates dug up a news picture. There he was, and there was the date.” She says, “If he wasn’t [at the university], he couldn’t have killed her. If he didn’t kill her, why kill himself?” Gordon continues, “That’s it. So instead of a murder and a suicide, we have something else – two murders. Do you want to go a step further?” She responds, “The man who killed Dorothy is still free.” Gordon says, “That’s right…As far as I’m concerned, the case is just starting. I’ll keep you posted.” Presented with a golden opportunity to resume being a “girl detective,” Ellen rejects it. The role of the detective in the film is taken over by Gordon.

The way Gordon gets the evidence that Bud knew Dorie before Ellen is very different in the novel than in the film. In the book, Gordon reads a letter that Ellen is writing to Bud about her visit to Dorie’s university, Stoddard. From the letter, Gordon deduces that Bud is attending Ellen’s small college, Caldwell, and he is an upperclassman. Moreover, Gordon figures out that Bud has transferred to Caldwell from Stoddard, which he had attended as an underclassman at the same time as Dorie. Gordon explains this to Leo, as well as why he believes Bud has never told Marion, Leo’s third daughter, that he knew Dorie. But the father refuses to believe Bud had a relationship with his two other daughters, much less that he killed them. Also, Leo feels sure that Bud has told Marion that he was at Stoddard when Dorie was there. (213-218)

In search of better evidence, Gordon breaks into Bud’s home and steals a “strongbox.” Forcing it open, Gordon finds documents that incriminate Bud. Marion is convinced by Bud’s handwritten notes on what he needed to learn in order to impress her: specific novelists, poets, painters, and playwrights, as well as Italian and Armenian restaurants in New York City. (244-245) Leo is convinced by the dates when Bud twice ordered brochures about the Kingship copper company – first when he was at Stoddard (courting Dorie) and then after he transferred to Caldwell (courting Ellen). (247-248) At last, Gordon succeeds in making Leo and Marion realize: Bud will stop at nothing to marry a Kingship “girl”; he has already murdered Dorie and Ellen; and, with Marion’s wedding to him only days away, she mustn’t marry her sisters’ killer.

Here again, the book differs from the film. Based on the papers that Gordon shows Marion, her love for her fiancé immediately ends. Later, in the novel’s climax above a fiery smelter, Marion, standing behind Leo and Gordon, presses her fingers into their shoulders as if to push them forward in their confrontation with Bud. (267-270) In contrast, Ellen’s behavior in the film is at odds with Marion’s, as well as Miklitsch’s interpretation of it.

In the film, after Gordon tells Ellen that Dwight couldn’t have murdered her sister, she introduces him to Bud, who, as her fiancé, is already on hand at their wedding engagement party. Beforehand, however, Bud tries to avoid Ellen – so that she can’t make that introduction. And there is a sound reason why Bud doesn’t want to meet Gordon.

Once Gordon leaves the Kingship house, he goes to a nearby gas station, where he makes payphone call to his uncle. He tells him that he thinks “the guy” Ellen is going to marry he has “seen before…at the university…with Dorothy Kingship.” He asks his uncle to find out about “Bud Corliss” at the registrar’s office and to call him back. Then, he returns to the Kingship’s and meets with Leo. Gordon says he believes Bud knew Dorie at the university. He admits he lacks proof, but he assures Leo that his uncle “is checking on it.” Gordon suspects that, after Bud transferred to Ellen’s college, he never told her he had known her sister. Gordon convinces Leo the issue is so serious that Ellen should be asked whether she knew about Bud and Dorie. When Leo raises the question, she emphatically calls it “a lie.” Furthermore, she walks away from them and says, “Don’t ever mention this to me again. Not any part of it. Not ever.”

Why is this her response? Because after Dwight’s death, Ellen stops being a detective. All she cares about is her romance with and coming marriage to Bud.

What Miklitsch calls “the concluding, climatic sequence” is actually two sequences that are intercut. As he says, “…Ellen drives Bud out to her father’s smelter….” (194) Yet he doesn’t mention that, at the same time at the Kingship house, Gordon has Leo take a phone call from his uncle, who says, “This is the confirmation on it, Mr. Kingship. Corliss was Dorothy’s boyfriend all right. The waitress says they came here often, for several weeks before she died.” After they learn where Ellen has gone with Bud, Leo and Gordon drive off to the smelter.

In a cut-back to the copper mine, Ellen and Bud are shown making stops so that he can revel in one breathtaking view after another of the Kingship’s ore wealth. Although Bud makes a blunder, Miklitsch is mistaken about its consequence. He writes, “[W]hen Bud reflexively corrects Ellen about how long her father’s company has been mining the pit and she responds, ‘Darling, you sound like you knew the Kingship mine long before the Kingship girl,’ his masquerade begins to crumble.” (194) Miklitsch suggests that now Ellen becomes cunning (“leading him on”). As Bud has never told her that he attended Dorie’s university, she tricks him into admitting he went to concerts of Debussy’s music in Lupton. Ellen is starting to wonder whether Bud did, in fact, know Dorie, but she isn’t suspicious that he was about to marry her.

This is the scene where Miklitsch opines that Ellen “transitions from being a potential victim to a private eye.” (195) However, he ignores what really occurs between Ellen and Bud. Recognizing that Ellen is sensing betrayal, Bud confidently and convincingly justifies why he never told her that he had known Dorie and “even had a few dates with her.” Ellen remains upset that he kept this secret. So Bud raises the stakes by feigning how he feels put upon by her. He questions whether she really loves and trusts him; then he walks away from the car. Distressed that she has angered him, she runs after him and into his arms.

Bud succeeds in allaying Ellen’s suspicions. But in his triumphant moment he overplays his hand. He haughtily asks whether Gordon “put [her] up to this” (to make her doubt him). She replies that Gordon talked to her about Dwight, who “was killed by the same man who killed Dorothy.” At last, she begins making connections that before she had either ignored or rejected, such as why Dwight’s killer knew where he lived. Bud insists that these are just coincidences. Ellen is unfazed, “Right beside me all along.” Bud then gives himself away for good, “What does it mean? Nothing. Dorie knew a dozen….” He breaks off, alarmed. Inadvertently, the killer unmasks himself. She stares at him and says, “Dorie! There weren’t a dozen who called her Dorie. There was only one.”

As Ellen tries to prevent Bud from pushing her off the precipice of the deep copper mine, there is a cut to Gordon and Leo watching the struggle from their car. By the time they reach Ellen, she has survived Bud’s attack and, after he is hit by a huge dump truck, he is dead at the bottom of the pit.

The film’s climax is the second scene in which Ellen wears her pink and white checked dress. Since she isn’t being a private eye, Miklitsch’s association between the dress and detecting is inaccurate for this scene. Of course, if it isn’t true for both scenes, then it isn’t a valid observation at all. Nonetheless, a connection does exist between the scenes. In the first, Ellen tells Gordon that she wants to “identify [Dorie’s] boyfriend” because she believes that he is her sister’s killer. In the second, Ellen has her answer. She doesn’t learn it through investigation. She gets it unintentionally because of Bud’s error, which turns out to be a fatal one for him. Still, it is appropriate that Ellen finds out the identity of Dorie’s murderer when she is wearing that particular dress.

There is no gainsaying it: 1) Robert Miklitsch is wrong to claim that Ellen is a “girl detective”; 2) Gordon is the detective, not Ellen; and 3) Ellen, instead, is Bud’s loyal lover until he makes one mistake too many.