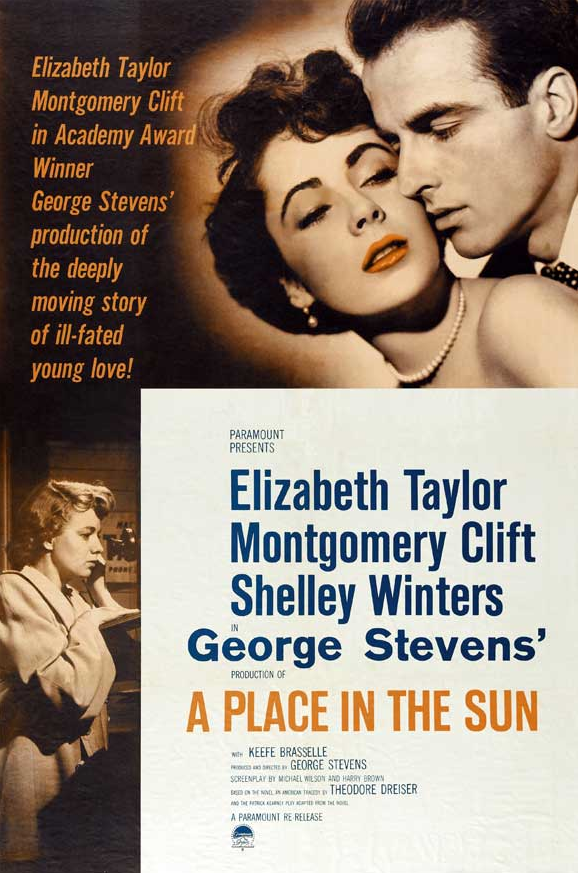

A Place in the Sun

Main Credits

Director: George Stevens. Screenplay: Michael Wilson, Harry Brown based on novel An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser and play An American Tragedy by Patrick Kearney. Producer: George Stevens. Associate Producer: Ivan Moffat. Director of Photography: William C. Mellor. Music: Franz Waxman. Art Director: Hans Dreier, Walter Tyler [Walter H. Tyler]. Editor: William Hornbeck. Costume Designer: Edith Head. Cast: Montgomery Clift (George Eastman), Elizabeth Taylor (Angela Vickers), Shelley Winters (Alice Tripp), Anne Revere (Hannah Eastman), Keefe Brasselle (Earl Eastman), Fred Clark (Bellows, defense attorney), Raymond Burr (Dist. Atty. R. Frank Marlowe), Herbert Heyes (Charles Eastman), Sheppard Strudwick (Anthony ‘Tony’ Vickers), Frieda Inescort (Mrs. Ann Vickers), Kathryn Givney (Louise Eastman), Walter Sande (Art Jansen, George’s Attorney), Ted de Corsia (Judge R.S. Oldendorff), John Ridgely (Coroner), Lois Chartrand (Marsha), Paul Frees (Rev. Morrison, priest at prison). Released: Paramount, August 14, 1951. 122 minutes.

From Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

Plot Summary

With postwar increases in education, incomes and career opportunities, especially for young white male veterans such as George Eastman, director Stevens’ decision to portray America as an open class system (signaled in the film’s title, A Place in the Sun), eschewing Dreiser’s view in An American Tragedy that it was closed, should be placed in historical context. George, both low-skilled and low-educated, accepts an offer to work in his uncle’s swimsuit plant. From afar, he is attracted to Angela, the belle of the young and the rich. Since his relatives don’t include him in their elite social life, he starts dating Alice, who packs swimsuits at the factory. He gets her pregnant. Unexpectedly, his uncle promotes him and invites him to his next party, where George and Angela fall in love. The scene that represents the film’s strongest endorsement of class mobility takes place at her family’s lodge. Angela’s father asks George about his background. George replies he grew up poor and left home at thirteen “to do something about it,” taking any job he could get. This frankness wins her father’s approval for Angela to marry George. Spoiling everything, however, Alice shows up with her own demands for marriage. Alice can’t swim, so George takes her out in a rowboat on a deserted lake. Although he changes his mind about drowning her, the boat capsizes and she dies. George is arrested, tried and convicted on circumstantial evidence. Because he deliberately didn’t rescue Alice, a priest tells him, “In your heart was murder.” Just before George is executed, Angela tells him she will love him for the rest of her life.

Commentary

Janus (from which January is derived) was the mythical Roman god of doorways, beginnings and endings. He had two faces, which looked in opposite directions. They symbolized not only the moon and the sun but also time, since one face looked to the past and the other to the future. He represented such dichotomies as barbarity and civilization, rural and urban living, and youth and adulthood.

In multiple ways, A Place in the Sun is the Janus-film of its time. The original theatrical trailer says, “One love grew in the shadows of night. The other love flamed in the bright light of gaiety and laughter.” Not only does each of these love stories have a distinct visual style but each style is associated with a different time. Their affinity with Janus is that the style for love in the shadows looks backward toward film noir of the 1940s, whereas the style for love in bright light looks forward to the romantic melodramas of the 1950s.

Indeed, each of these kinds of cinema, film noir and melodrama, is represented by a different face, that of Alice and Angela, respectively. In fact, to face in different directions is how the film begins. As the credits roll, George stands by the side of a highway, his back to the camera. Trying to hitchhike a ride to go forward, he looks at where he has already been. The music swells as he walks backward nearer to the camera. Once the credits end, he turns around and the camera moves in close. He is smiling at his destination, signified by a billboard for Eastman swimsuits. A car horn honks behind him, and he turns with his thumb out. Angela drives by in a white convertible, ignoring him. The camera and then George’s eyes pan after her, as she drives on. Now he faces the direction of his future.

The locations for George’s two romances are polarized in class terms, between proletariat and bourgeoisie, the Eastman factory and Alice’s city apartment vs. the Eastman suburban mansion and Angela’s lakeshore lodge. The romances are also associated with time, which mark the different class situations of George’s life. Alice is part of his working class past. He and she immediately catch each other’s eye and easily hit it off. Angela is the potential in his future. Since they come from very different worlds, on the first couple of occasions when they cross paths, she literally doesn’t see him.

Above all, however, the most striking contrast in A Place in the Sun is the different visual style that is used, on the one hand, for George’s relationship with Alice and, on the other, with Angela. Each style is appropriate to its associated narrative, as well as the dichotomies of time and social class in George’s life.

On George’s first day at work, his cousin, Earl, takes him on a tour of the plant. As they walk out of a room where lovely women are modeling Eastman bathing suits, George turns his head to look back. Earl notices it and immediately warns him, “There’s a company rule against any of us employees mixing with the girls who work here. My father asked me to particularly call this to your attention. That is a must!”

This incident contradicts the theatrical trailer’s assertion that “fate weaves the strange fabric of his life.” George’s life isn’t destined to end tragically. He chooses to disobey an explicit rule imposed by those who run the factory as well as the community. It is his fault, and not fate, that his place will be in the electric chair instead of in the sun. He should have always looked ahead and complied with new class obligations, never looking back to the working class (swimsuit models or packers) that he should renounce.

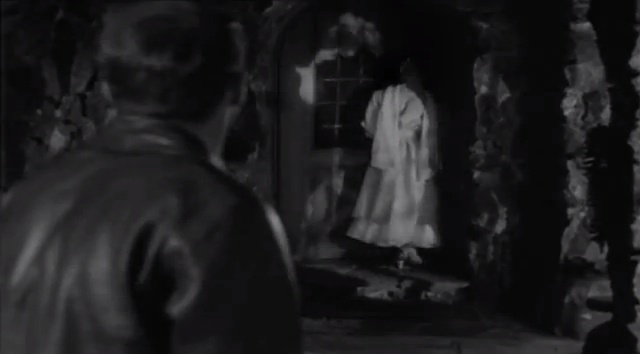

However, since George does disobey, he and Alice have to hide their affair. In the style of film noir (A Place in the Sun is shot in black and white), the key incidents of George and Alice’s affair are set in shadows: their first kiss; the night they sleep together; their conversation in his car after a doctor refuses to perform an abortion; when George hears a radio report about people drowning and gets the idea to murder Alice; and the final six-minutes of the scene when Alice drowns and George survives.

The shadows that conceal George are also the shades of time and class in his life. As he moves up the corporate ladder, his origins in the working class are supposed to disappear into the past. Time fading is also emphasized via frequent prolonged dissolves, as one scene slowly transforms into another. Because the old scene is as visible as the new, the overlapping creates a Janus-effect by simultaneously showing past and future.

In contrast, and anticipating the lush color cinematography of the remarkable melodramas soon to come, George and Angela’s romance is shown in bright light and, most famously, tight close-ups. Angela’s association with brightness extends to her clothing. She is often dressed all in white, in a dress, or a full-length coat with a white scarf around her head. In the first half of the movie if she is wearing black, it is under a striking white accessory (a mink stole, a jacket or a Hawaiian lei).

George’s future — upper management at the plant, marriage to Angela and membership in the community’s high society — is associated with a bright visual style. His passion for Angela, as opposed to his alienation from Alice, is evidenced through close-ups. Alice’s only close-up with George (which is medium, not tight) occurs in the rowboat when she asks him if he wishes she were dead. Moments later she plunges into the lake.

Angela, on the other hand, may be one of the characters in Hollywood history most identified with close-ups. When she has her first conversation with George in the poolroom at his uncle’s house, she is photographed close up and in soft focus. Afterwards, as they dance, the camera moves in even nearer to her face. The huge close-ups continue while Alice is alive. However, Alice’s death finishes the film’s two separate yet intertwined stories.

In the single narrative that concludes the film (George’s trial and punishment) the film noir of A Place in the Sun eclipses the romantic melodrama. Prefiguring this, the visual style for the love that began in bright light turns dark. At the lake where Alice will drown, Angela sits on shore in a strapless black swimsuit (no cap) looking outward with her back to the camera, as she tells George about a woman who drowned there and whose male companion was never found. When George and Angela kiss the day before Alice dies, Angela’s face is unseen in shadows. Prior to his arrest, they kiss in front of her lodge, and then Angela steps through the doorway into darkness.

George and Angela aren’t together again until she comes to his cell. Her appearance is the opposite of their first meeting in the poolroom, when she wore a strapless white dress over petticoats. At the prison she wears a conservative, full-length black dress appropriate for a funeral, with only a small white collar and a black cap covering her hair. The film ends with George facing the camera as he walks toward the execution room. At this moment the film noir and the melodrama converge. Superimposed over a screen-filling close-up of George’s face is Angela’s, as she’s being kissed in his memory. In the film’s last shot, their two faces, like Janus, are embodied in one.