The Sweetheart & the PI

Introduction

At the end of many private eye film noirs, he winds up with – to use Philip Marlowe’s expression in Murder, My Sweet – “soft shoulders,” a sweetheart. These numerous romantic conclusions undermine the legitimacy of the PI as an icon of the film noir hardboiled paradigm. That is, how can the private dick be considered one of the embodiments of the hardboiled tough guy character prototypes when, in 15 of 33 films, he is head over heals in love with a dame?

(For the titles of the 33 private eye film noirs, see the page The Missing PI in Film Noir.)

Presentation

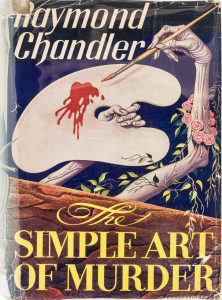

The prevalence of the detective’s sweetheart undermines the coherence of the film noir hardboiled paradigm itself. Contrast the outcomes of the near majority of the private eye film noirs – with a romantic couple created by the detective and his sweetheart – and the description of the PI in Raymond Chandler’s famous essay, The Simple Art of Murder.

“I do not care much about his private life; he is neither a eunuch nor a satyr; I think he might seduce a duchess and I am quite sure he would not spoil a virgin…He is a lonely man….” (last paragraph)

Chandler’s explanation of the hardboiled private detective pertains to an ideal literary character. In the “classic era” (1940-1959), his books were the basis for the following film noirs: The Big Sleep (The Big Sleep) Farewell, My Lovely (Murder, My Sweet), The High Window (Time to Kill and The Brasher Doubloon), and The Lady in the Lake (Lady in the Lake). At the end of each novel, Chandler’s PI, Philip Marlowe, is “a lonely man.” However, at the finish of each film noir, Marlowe has a sweetheart.

Chandler’s explanation of the hardboiled private detective pertains to an ideal literary character. In the “classic era” (1940-1959), his books were the basis for the following film noirs: The Big Sleep (The Big Sleep) Farewell, My Lovely (Murder, My Sweet), The High Window (Time to Kill and The Brasher Doubloon), and The Lady in the Lake (Lady in the Lake). At the end of each novel, Chandler’s PI, Philip Marlowe, is “a lonely man.” However, at the finish of each film noir, Marlowe has a sweetheart.

There is a marked contrast between hardboiled detective Chandler theorized for literature and the private eye so frequently seen in film noir. The PI in film noir who not only solves a mystery but also gets a sweetheart doesn’t conform to Chandler’s model. In fact, it may be questioned to what extent he is actually hardboiled.

The importance of romance in private eye film noirs is not to be lamented. It simply has to be acknowledged. Adherents of the film noir hardboiled paradigm, however, have failed to do so. In the teeth of the contradictory evidence, they have associated the shamus in film noir with the prototype hardboiled detective that Chandler described in “The Simple Art of Murder,” as well as the Philip Marlowe character of his crime stories.

Not only has the private detective’s significance as a character type been grossly inflated because there are so few gumshoes in film noirs in the classic era, his lifestyle has been misrepresented because, often as not, the PI isn’t a lonely man but a lover man. (Regarding the paucity of private eyes in film noir, see the page The Missing PI in Film Noir.)

Furthermore, it must be emphasized that there isn’t a bifurcation, in terms of romance, between those private eye film noirs that end with a sweetheart and those that end darkly if not tragically. In the former the detective goes about his investigation without being love-smitten. The woman who will wind up as his sweetheart doesn’t romantically distract him. In contrast, some of the film noirs with bad endings for the PI have plots that highlight a woman as the detective’s love interest. That is, romance is more key in these film noirs that when the private eye winds up with a sweetheart.

In World for Ransom Mike Callahan (Dan Duryea) has loved Frennessey March (Marian Carr) for a long time, and he still carries a torch for her even though she is married. He risks his life to help husband only because she promises to go away with him afterwards. Her husband dies in any event, but instead of keeping her promise, she reveals it had all been a lie. She rebuffs Mike, leaving him alone and no longer deceived that he still has a chance to be with her. (For more about Frennessey as a “deceitful client,” see the page The Killer Client & the PI.)

Out of the Past presents what may be, in all of film noir, the most deeply felt love by a private eye for a woman. The question, however, posed at the end of the film, is which of two women does he love more?

At the beginning of the story, Jeff Bailey (Robert Mitchum) is the owner of a gas station. His girlfriend in a small town is Ann Miller (Virginia Huston). Years earlier he was Jeff Markham, private investigator. He was hired by Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas) to find Kathie Moffat (Jane Greer) after she had shot Whit and taken $40,000 from him. Jeff finds Kathie in Acapulco, and they start a passionate affair.

Although Kathie is perhaps film noir’s most infamous femme fatale, her romance with Jeff defies any facile pigeonholing, such as that she is only a betrayer, and he is only a sucker.

Matters of the heart are so vital to Out of the Past that it ends with Ann asking a boy, The Kid (Dickie Moore), a close friend of Jeff’s, whether Jeff was really going to leave her for Kathie. Jeff and Kathie are now dead (Jeff was murdered by Kathie, and Kathie was killed by the police). To spare Ann’s feelings, The Kid, a mute, lies by nodding his head for yes. The deception allows Ann to break free from her past romance with Jeff. It also enables her to give her heart to Jim (Richard Webb), a local law officer who is in love with her.

The film closes with The Kid smiling and nodding at the sign above Jeff’s gas station. We, and Jeff’s spirit, as it were, know the truth: Jeff intended to finish his business with Whit and come back to Ann.

In Grand Central Murder, the private detective is married, and his wife helps him unmask the killer. She comments on how many beautiful women in New York City speak to him by name when they pass by: “You know so many people, don’t you, dear. Most of them ‘she’s’.” Still, she isn’t just his spouse but she is also his sweetheart.

Contrary to the film noir hardboiled paradigm, private eye film noirs – as few as they are – have neither the hardboiled characters nor the stories transferred in tact from literature to cinema. Instead, private eyes film noirs are typically alternative Hollywood romances. They have a different milieu in which a man (the PI) and a woman come together. Nonetheless, like so many other kinds of tales from Tinseltown, their plots serve the purpose of getting him to fall in love with her, and she of course is already in love with him. And then, “The End.”

Private Eye Film Noirs with a Sweetheart: title, date, sweetheart (actor), private eye (actor)

The Maltese Falcon, 1941, Brigid O’Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart). After Spade tells O’Shaughnessy that he loves her, he says that if she isn’t hanged for murder and if she gets time off for good behavior, he will be waiting for her when she is released from prison in 20 years.

Grand Central Murder, 1942, Sue “Butch” Custer (Virginia Grey), “Rocky” Custer (Van Heflin)

Time to Kill, 1942, Linda Conquest Murdock (Doris Merrick), Michael Shayne (Lloyd Nolan)

Murder, My Sweet, 1944, Ann Grayle (Anne Shirley), Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell)

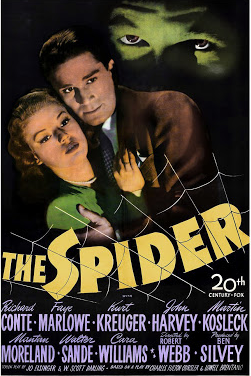

The Spider, 1945, Delilah “Lila” Neilsen (Faye Marlowe), Chris Conlon (Richard Conte)

The Big Sleep, 1946, Vivian Sternwood (Lauren Bacall), Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart)

The Dark Corner, 1946, Kathleen Stewarth (Lucille Ball), Bradford Galt (Mark Stevens)

The Last Crooked Mile, 1946, Bonnie (Adele Mara), Tom Dwyer (Don Barry)

The Mysterious Mr. Valentine, 1946, Janet Spencer (Linda Stirling), Steve Morgan (William Henry)

The Brasher Doubloon, 1947, Merle Davis (Nancy Guild), Philip Marlowe (George Montgomery)

High Tide, 1947, Dana Jones (Anabel Shaw), Tim Slade (Don Castle)

Lady in the Lake, 1947, Adrienne Fromsett (Audrey Totter), Philip Marlowe (Robert Montgomery)

My Favorite Brunette, 1947, Carlotta Montay (Dorothy Lamour), Ronnie Jackson (Bob Hope)

Riff-Raff, 1947, Maxine Manning (Anne Jeffreys), Dan Hammer (Pat O’Brien)

I Love Trouble, 1947, Norma Shannon (Janet Blair), Stuart Bailey (Franchot Tone)

Behind Locked Doors, 1948, Kathy Lawrence (Lucille Bremer), Ross Stewart (Richard Carlson)

Guilty Bystander, 1950, estranged wife Georgia Thursday (Faye Emerson) reconciled with her husband Max Thursday (Zachary Scott)

Addendum

Time to Kill: Michael Shayne (Lloyd Nolan), Myrle Davis (Heather Angel), Linda Conquest Murdock (Doris Merrick). Despite having a lesser role in the film, Angel got higher screen billing than Merrick.

Time to Kill: Michael Shayne (Lloyd Nolan), Myrle Davis (Heather Angel), Linda Conquest Murdock (Doris Merrick). Despite having a lesser role in the film, Angel got higher screen billing than Merrick.

In the list above of private eye film noirs with a sweetheart, note that in the two versions of Raymond Chandler’s novel, The High Window (Time to Kill and The Brasher Doubloon), the killer client is the same character, Mrs. Murdock, but not only is the private eye different (first Michael Shayne, then Philip Marlowe) but so, too, is his sweetheart. At the end of Time to Kill, Mrs. Murdock’s daughter, Linda Conquest Murdock, is set to marry Shayne. In this version Mrs. Murdock’s secretary, Myrle Davis, offers no romantic competition. In contrast, Mrs. Murdock doesn’t have a daughter in The Brasher Doubloon, but she does have a secretary, similarly named Merle Davis. With no other young female in the cast, she becomes Marlowe’s sweetheart.