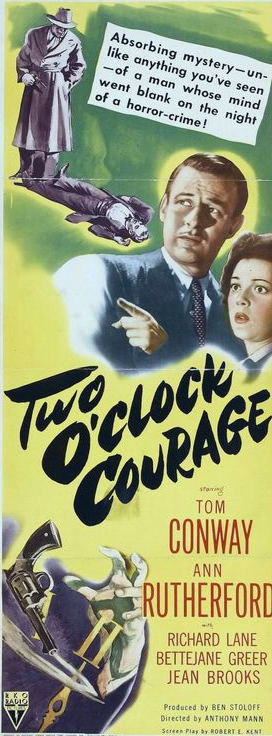

Two O’Clock Courage

Introduction

Below I use Two O’Clock Courage as a case study of the plot elements of the “war noir,” which I extensively describe in the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar.

Main Credits

Director: Anthony Mann. Screenplay: Gelett Burgess. Producer: Ben Stoloff. Director of Photography: Jack MacKenzie. Music: Roy Webb. Cast: Tom Conway (The Man, Ted ‘Step’ Allison), Ann Rutherford (Patty Mitchell), Richard Lane (Al Haley), Lester Mathews (Mark Evans), Roland Drew (Steve Maitland), Emory Parnell (Insp. Bill Brenner), Bettejane Greer (Helen Carter), Jean Brooks (Barbara Borden). Released: RKO Radio Pictures, April 13, 1945. 68 minutes.

From Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

Plot Summary

At the end of Two O’Clock Courage, Ted and Patty are married. Ted, who was the prime suspect, has been cleared of suspicion of murdering Robert, a theater producer. Barbara is the killer. Robert threatened to show the letters she had written him to Steve, her jealous boyfriend. Barbara and Steve are starring in a play that Mark has falsely taken credit for writing. Robert, who is producing the play, knows Mark is a plagiarist and has made Mark share the royalties with him. Ted knows the real author was Larry, who has been mysteriously murdered. Just after Ted tells Robert that all the royalties belong to Larry’s mother, Barbara kills Robert and knocks Ted out. At the start of the film, Ted has come to, but he has amnesia. He meets Patty, a taxi driver. She helps him find out his identity, and they fall in love. (It is never revealed who killed Larry. Presumably, Mark killed him to collect the royalties.)

Commentary

Two O’Clock Courage has the same array of plot elements that are in several other early film noirs, from 1940-1944. These elements aren’t representative of postwar film noir. The following six plot elements are characteristic, in part or en toto, of wartime film noir. Examples are taken from Two O’Clock Courage.

First, crimes are about “personal” property, not “public” property. (Bank-robbing or racketeering is public. What is intimately associated with a person – his or her own life or money – is personal. Royalties for Larry’s play are personal. During the war years, there is almost no film noir with a public property crime. However, it is pervasive in postwar film noir.)

Second, the police fail to catch the criminal, or they are absent from the story. (Thanks to Ted and Patty, the investigation succeeds. The city police are comic. Postwar law enforcement – which is usually state or federal, not local – consistently catches the criminal. Furthermore, several postwar film noirs, like Anthony Mann’s T-Men, are depictions of the competency of federal law enforcement agencies.)

Third, unless there is espionage, the murder is committed out of passion (anger or jealousy), like Barbara’s motive for killing Richard.

Fourth, along with a murder from passion, there is a whodunit, like who killed Richard. (In postwar film noir, there is rarely a “puzzle” because it is known who is guilty. In fact, the story is often about someone who is guilty.)

Fifth, the leading man, who is falsely jailed or hunted by the police, has to prove that he is innocent of murder, like Ted. (As a rule in postwar film noir, the accused criminal is guilty, whatever the crime.)

Sixth, a woman helps crack the mystery. She has both a job and a brain, like Patty. (In postwar film noir, women are no longer a man’s crime-solving “ally.” Instead, they are likely to be a woman in distress, a femme fatale or a homemaker.)

Some examples of early film noirs with this “formula” are: Stranger on the Third Floor, Fly-By-Night, I Wake Up Screaming, Saboteur, Street of Chance, Phantom Lady, When Strangers Marry, and Ministry of Fear.

Other early film noirs may not have the complete array, but they have at least some of these plot elements. All six plot elements in combination, which comprise the “war noir” formula (i.e., they only come together during WWII), don’t similarly combine in postwar film noirs. For example, in two of Mann’s later film noirs, Desperate and Side Street, a woman merely accompanies a man. Two O’Clock Courage marks the final hour for the working-class woman who has wit, wits and moxie, and actively tries to clear a man.

Addendum

For a comprehensive analysis of war noirs, plus a complete list of the films – including spy noirs as well as crime noirs – see the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar.