Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir in the UK & US

The Unrecognized History in Film Noir

In Five Graves to Cairo, Corporal John J. Bramble (Franchot Tone), like many men and women in an espionage story, becomes an imposter. He is a survivor of the British Eighth Army in North Africa, which was, according to the film’s introduction, “beaten, scattered, and in flight” in June 1942. He makes it across the desert to an isolated hotel, The Empress of Britain. Despite its bold name, its ramshackle condition implies that the UK is no longer the nation that rules the world.

A short time later, the German Afrika Korps arrive, and the hotel is commandeered by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (Erich von Stroheim). Bramble pretends to be the hotel’s French waiter, Paul Davos, who was killed when the Nazis bombed the area the night before. Bramble later discovers that the real Davos also had a secret life – he was a German agent. Taking advantage of this knowledge, Bramble deceives Rommel and gains his confidence.

The Desert Fox shows Bramble a map of Egypt. He says the British officers that he has captured wouldn’t be able to figure out where the Germans had “dug supplementary supplies into the sands of Egypt,” even if they were to see the map. Because Rommel thinks Bramble isn’t British, he assumes the waiter can simply look at it and spot “the five graves to Cairo,” the locations with buried “petrol, water, ammunition, and spare parts for tanks.”

Bramble knows if the British destroy these depots, the Nazis can be defeated in North Africa. As he studies the map, he disguises his inability to decipher it by saying to Rommel, “I’m trying to look at it with an Englishman’s eyes. Not a clue. Just an ordinary map.”

Hours later, he realizes the supplies are hidden where the map has the letters E, G, Y, P, T.1

[The reference for footnote #1 above, and the references for 67 more footnotes below, are at the end of this post under “Notes.” Afterwards, there are citations of books, alphabetically listed in three categories, under “Bibliographies.”]

Similarly, since 1946, with the publication in France of “the two earliest essays on Hollywood film noir,” mass media journalists and academic historians haven’t seen what was fundamental in the origins of film noir, even though it was right in front of their eyes.2

Here, I offer a new interpretation about the beginning of film noir in Britain and the United States. Put simply, the earliest film noirs in these countries were spy films nearly as much as crime films. These “spy noirs” were released during the Second World War era: in the UK, as of the mid-1930s; in the US, as of the late 1930s; and culminating in both countries in the immediate years after the war ended.

Recognition of spy noirs makes undeniable the historical context of the WWII era in the origins of Anglo-American film noir. (This post doesn’t address French film noirs released in the 1930s.3)

Please see my accompanying four tables of UK and US spy noirs. For each country, one table presents spy noirs that are cited in film noir reference books, although they aren’t called “spy noirs.” Also, for each country, there is a table in which I identify spy noirs, based on my own judgment, that haven’t been named in any reference books. (My research shows that most UK and US spy films released during the WWII era aren’t spy noirs. Nonetheless, as my tables indicate, a significant number of UK and US spy films, according to my criteria, deserve to be recognized as spy noirs, despite not being cited as such in film noir reference books.)

Key to the Definition of Spy Noir: Visual Style

While not a condition of a crime film, any spy film, no matter how far removed from events in the real world, is unmistakably associated with politics. A spy film has at least one main character whose real identity is unknown to the political enemy and who is engaged in secret activity against that enemy, which is typically a rival nation. The laws that are broken in spy films, as with the lawbreakers themselves, are unlike those in crime films. In short, spy films are distinct from crime films.4

What differentiates spy noirs from other spy films is the same “noir visual style” (or “noir style”) that separates crime noirs from other crime films.5 Therefore, it stands to reason that spy films with the noir style comprise a unique category of film noir. It is on this basis that I use the term spy noir and counterpose it to crime noir.

Below there are photographs (screen-captures) from a range of UK and US spy noirs that show the noir style. Furthermore, there are videos (scene-captures) that underscore the validity of including UK and US spy noirs in the filmography of film noir.

Take the following scene in Five Graves to Cairo. During an air raid, everyone in the hotel seeks shelter in the basement. There, amidst the rubble from the previous air raid, a Nazi lieutenant (Peter van Eyck) discovers the corpse of the real Paul Davos. From the officer’s close questioning, Bramble realizes he is about to be killed for his impersonation. The ensuing chase through the hotel is a fine demonstration of the high quality of the noir visual style that is in spy noirs.

In Eyes in the Night, a blind man, “Mac” Maclain (Edward Arnold) prevents pro-Nazi fifth columnists from stealing the design for a secret airplane invention.

In Eyes in the Night, a blind man, “Mac” Maclain (Edward Arnold) prevents pro-Nazi fifth columnists from stealing the design for a secret airplane invention.

A butler, Hansen (Stanley Ridges), is Maclain’s main adversary. However, it is a woman (Katherine Emery) who is the ringleader.

A butler, Hansen (Stanley Ridges), is Maclain’s main adversary. However, it is a woman (Katherine Emery) who is the ringleader.

Spy films are included in several film noir reference guides, yet none of them recognizes spy noir as its own classification within film noir.6 My research indicates the number of spy noirs in these filmographies is less than half of the actual total. My own selections of UK and US spy noirs tend to exhibit at least as much – if not more – of the noir style as spy films cited in the reference books.

There have always been disagreements as to whether a particular crime film is or isn’t a film noir. I expect conflicting opinions about spy films. I acknowledge I have stronger selections (China Girl) and weaker ones (Conspiracy). Regardless, a sufficiently obvious and consistent noir style is evident in all of my choices. Spy films that lack an unambiguous noir style aren’t in my tables.

In China Girl, an American news photographer/pilot, Johnny Williams (George Montgomery), fights off thieves who want a valuable artifact that he is carrying on behalf a beautiful, enigmatic Chinese woman, Miss Haoli Young (Gene Tierney).

In China Girl, an American news photographer/pilot, Johnny Williams (George Montgomery), fights off thieves who want a valuable artifact that he is carrying on behalf a beautiful, enigmatic Chinese woman, Miss Haoli Young (Gene Tierney).

After Williams and Young fall in love, they survive a Japanese bombing raid. In a subsequent attack, Young is not as fortunate, and Williams converts from being unconcerned about the conflict to a warrior on China’s side.

After Williams and Young fall in love, they survive a Japanese bombing raid. In a subsequent attack, Young is not as fortunate, and Williams converts from being unconcerned about the conflict to a warrior on China’s side.

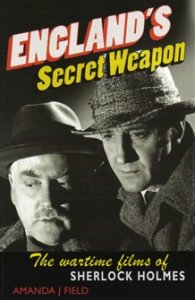

Of the hundreds of WWII-era spy films I analyzed, I was able to use the noir style as the criterion to discern which ones were spy noirs because there was never a doubt whether the story in any particular spy film was “noir” enough. That is, the plots and characters in spy films don’t need to be scrutinized to determine if they are adequately equivalent to those in crime noirs. For example, in England’s Secret Weapon: The Wartime Films of Sherlock Holmes, Amanda J. Field’s insight about Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror suggests an essential difference between a crime film and a spy film.

Of the hundreds of WWII-era spy films I analyzed, I was able to use the noir style as the criterion to discern which ones were spy noirs because there was never a doubt whether the story in any particular spy film was “noir” enough. That is, the plots and characters in spy films don’t need to be scrutinized to determine if they are adequately equivalent to those in crime noirs. For example, in England’s Secret Weapon: The Wartime Films of Sherlock Holmes, Amanda J. Field’s insight about Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror suggests an essential difference between a crime film and a spy film.

“If Holmes is serving the Allied cause, then it follows that his enemy will be the Nazis. This involves an interesting departure from the usual pattern of the classic detective genre, in which crime is assignable to one errant individual. In a war, the enemy is like the hydra – in cutting down one, a hundred more spring up to take its place.”7

Espionage means clandestinity, conspiracy and treachery. Film characters (and movie audiences) may only find out who is on which side in or near the last scene. During the WWII era, men and women, whatever their political allegiances, are at least as ruthless in spy noirs as crime noirs. Unsurprisingly, in these years, there is much more violence in spy noirs than crime noirs.8

The Five Main Types of Plots in Spy Noir

The main types of plots in spy noirs are as follows: Good Spies, Bad Spies, Resistance Fighters, Fifth Columnists, Converted to the Allied Cause.

For some films, of course, more than one type may be suitable. To illustrate a specific element of a plot type, I include one or more titles of relevant spy noirs.

Following each explanation of a plot type, I cite multiple titles of appropriate spy noirs from the UK and the US. These examples favor films with lead roles by women to highlight the significance and scope of females in spy noirs. (Throughout this post, titles in groups are named in the order of their release.)

I. Good Spies

The key undercover activity is by at least one spy who is British or American. Other good spies are trained government agents or if they are civilians, they are either working for their home country or acting on their own. This kind of spy is one of the following nationalities: Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, Norwegian, Polish, or Russian.

A good spy is as likely to be a woman as a man. When someone is revealed in the finale to be a secret government agent, it is predictably a female. Here are six examples.

- Bulldog Drummond (John Lodge) believes a beautiful woman (Dorothy Mackaill) is a member of a spy ring. For example, he sees her put a drug in his tea to knock him out so that she can search his house for a piece of paper exposing the existence of the spy ring. (He “accidentally” spills the cup of tea.) In the penultimate scene of Bulldog Drummond at Bay, he discovers she is a British undercover agent who, like himself, is trying to bring down the spy ring. In the final scene, she telephones her boss to say she is retiring and marrying Drummond. Her superior congratulates her, adding “But I should be very sorry to lose such a brilliant and charming officer.”9

- In Navy Secrets, a woman (Fay Wray) and a man (Grant Withers) spend an evening together, at the end of which they bust up a spy ring. All along each of them had thought that the other was an enemy agent. At the conclusion they find out they are both in US Naval Intelligence. Still, the female is cleverer, more adventurous and assertive.

- In Enemy Agent, a draftsman (Richard Cromwell) at an aircraft factory is smitten with a hostess (Helen Vinson) at a nearby steakhouse. Cromwell’s colleague (Vinton Hayworth) is in a gang of fifth columnists. He uses a camera disguised as a watch to photograph Cromwell’s top-secret designs for a bombsight. He also frames Cromwell, who is jailed. After Cromwell turns his romantic attention to a waitress at the steakhouse (Marjorie Reynolds), he tells her that he has proof Hayworth is a spy. Reynolds mentions this to Vinson, who searches Cromwell’s apartment and then his car, where she finds the evidence he had hidden there. After the fifth columnists are captured by FBI agents, we find out Vinson is one of them – she is a “G-[wo]man.”

- British Intelligence, which takes place during WWI, has the most complicated disclosure of the good female spy. At first Helene von Lerbeer (Margaret Lindsay) is a German spy. For her outstanding service, the “Imperial Majesty” awards her a special bracelet. She also gets a new assignment and name. As “Frances Hautry,” supposedly a fugitive from a German detention camp, she is given sanctuary in the home of a British cabinet minister. There she meets the butler of the house, Valdar (Boris Karloff). The two acknowledge each other as fellow spies for the Kaiserreich. Later Valdar meets with members of British intelligence, suggesting that he is a double-agent. Back at the house, the newly arrived cabinet minister’s son recognizes Helene as the nurse he fell in love with when he was hospitalized in France. Valdar overhears Helene confess that she is working for the British secret service. Valdar is, in fact, the elusive German spymaster, Franz Shindler, who is the target of an elaborate British scheme to identify him. He is about to shoot Helene for being an enemy agent when she shows him the special bracelet. His belief in her loyalty to “the fatherland” restored, he reveals that he is Shindler. The film climaxes with Helene outing Shindler to the British secret service – she was all along the key to their plot to unmask him. In the final scene, a top official in British intelligence explains to the cabinet minister that no one but himself knew that Helene was so deep undercover.

- The final scene of The Saint’s Vacation first shows, to the shock of his two companions, that Simon Templar (Hugh Sinclair) hadn’t selfishly tried to obtain a mysterious music box, but instead it was on behalf of the British government. Next it is The Saint’s turn be surprised when he discovers a woman (Sally Gray) that he believed was plotting against him to get the box is actually an official agent.

- In Invisible Agent, the original Invisible Man’s grandson (Jon Hall) believes a lovely woman (Ilona Massey) that he has met – and who can’t see him – is a Nazi agent. Although he relies on her “training” to pilot a plane to get them from Germany to Britain, he thinks that if he lets her use the radio, she will inform the Nazis of their position instead of alerting the British not to fire at them with anti-aircraft guns. The plane is therefore shot down. While he recovers in a hospital from his parachute landing, the man (no longer invisible) is told that the woman is one of Britain’s “most trusted agents.” That is his revelation; hers is to see, at last, what the man she loves looks like.

A good male spy, who is a British or American civilian, may pretend to be a different person whom he identically resembles. Not only does he fool the real man’s friends and accomplices but also his wife, girlfriend or mistress (Nazi Agent, The Great Impersonation, Assignment in Brittany).

In each example below, the good spy is a woman.

UK – government agent: Dark Journey, Contraband (aka Blackout), Yellow Canary

UK – civilian: The Crouching Beast, The Man from Morocco

US – government agent: The Devil Pays Off, Dangerously They Live, Storm Over Lisbon

US – civilian: Espionage Agent, This Gun for Hire, Notorious

The following scene, presented in two parts, is a strong example of the noir style in the British spy noir, Contraband. It takes place in London in the underground hideout of a Nazi spy ring. In the first part, a Danish ship captain, Andersen (Conrad Veidt), and British secret agent, Mrs. Sorensen (Valerie Hobson), have been tied together and are being watched by the ring’s leader, Van Dyne (Raymond Lovell), whom they disparagingly call, “Mister Grimm.” When Hobson mentions “Mr. Pidgeon,” she is referring to her partner, who is still at large.

After Andersen and Sorensen trick Van Dyne into thinking they can’t escape from the rope that binds them, that is exactly what they do.

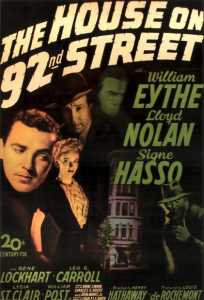

II. Bad Spies

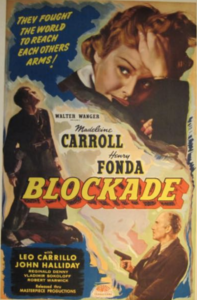

The key undercover activity is by at least one spy who is German or Japanese. Note that before the US entered WWII, many films didn’t explicitly refer to Japan or Germany as the enemy. For example, take the first two US spy noirs from 1938. International Settlement opens with newsreel footage of military assault on China by land and air. A voice-over (from well-known broadcaster Lowell Thomas) says, “The beautiful city of Peiping finds itself helpless against modern warfare.” Before the film’s conclusion, there is a 17-minute scene of an aerial attack on Shanghai, with the city’s population fleeing from bombs, crumbling buildings and massive fires. In the WWII era, this is the most extensive intermixing of Hollywood studio film and newsreel footage to depict China’s plight. Yet, Japan is never mentioned. Similarly, in Blockade, neither side in the Spanish Civil War – the Nationalists (supported by German Nazis and Italian Fascists) nor the Republicans – is named. Hollywood studios did this to avoid being politically attacked by “isolationists,” as discussed below, and to retain access to the movie market in the Third Reich.10

The first female star in both UK and US spy noirs was Madeleine Carroll. (See the Addendum below.) In Blockade, she and Henry Fonda survive a bombing raid by the unidentified enemy (i.e., fascists) on the civilians in a Spanish town. The film was released in June 1938, twelve months after Pablo Picasso painted Guernica.

The first female star in both UK and US spy noirs was Madeleine Carroll. (See the Addendum below.) In Blockade, she and Henry Fonda survive a bombing raid by the unidentified enemy (i.e., fascists) on the civilians in a Spanish town. The film was released in June 1938, twelve months after Pablo Picasso painted Guernica.

Guernica is the name of the village in northern Spain whose inhabitants, mainly women and children (most men were away fighting for the Republic), were attacked by German and Italian warplanes, at the request of the Nationalists, on 27 April 1937.

Guernica is the name of the village in northern Spain whose inhabitants, mainly women and children (most men were away fighting for the Republic), were attacked by German and Italian warplanes, at the request of the Nationalists, on 27 April 1937.

Bad spies are trained government agents or civilians who are recruited for espionage. A bad spy is as likely to be a woman as a man.

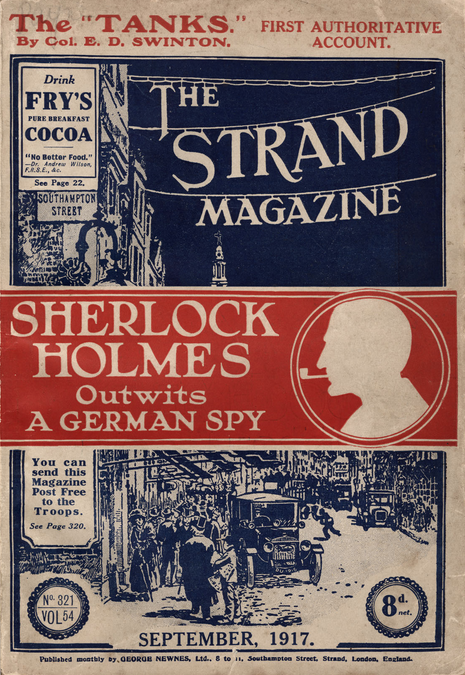

A bad male spy who masquerades as someone else based on physical resemblance is always German, never Japanese. He may be a natural double, with a proper accent, like the Prussian (Reginald Denny) who replaces a member of Britain’s elite and, on becoming a high government official, prepares a Nazi invasion of England (Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror). Or he may use theatrical artifice, like the stage actor (Raymond Lovell) who, with make-up and the ability to mimic another person’s speech, impersonates an English aristocrat in a Nazi scheme to kidnap Winston Churchill (Warn That Man).

In the UK examples below, the bad spy is a man, and in the US examples the bad spy is a woman.

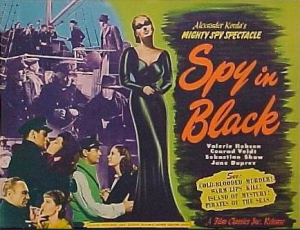

UK: The Spy in Black, Cottage to Let, The Next of Kin

US: The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt, Eyes in the Night, The Hour Before the Dawn

For an analysis of this spy noir, see the page The Spy in Black.

For an analysis of this spy noir, see the page The Spy in Black.

III. Resistance Fighters

The key underground activity is by resistance fighters who are on the side of the Allies. Like spies, if they are caught, they can expect to be put to death. They are Chinese (against the Japanese) or Czech, Dutch, French, Norwegian, Polish, and Yugoslavian (against the Germans).11

Although most resistance fighters are male, important leaders are often women. The underground may aid British or American servicemen to complete an espionage mission and/or escape from an occupied country (Nurse Edith Cavell, Bomber’s Moon, The Seventh Cross).

In The Seventh Cross, seven men are shown on the run after they flee from a Nazi concentration camp.

In The Seventh Cross, seven men are shown on the run after they flee from a Nazi concentration camp.

The film depicts how six of them, one by one, are captured and then lashed to makeshift crucifixes, on which they die.

The film depicts how six of them, one by one, are captured and then lashed to makeshift crucifixes, on which they die.

Only a single escapee, played by Spencer Tracy, gets away for good.

The Seventh Cross has one of the rare depictions of a Nazi concentration camp in a film released during the Second World War.12

Resistance may be with words instead of weapons. Because they courageously speak out against the Third Reich, the Nazis execute a minister (Pastor Hall), a schoolteacher (This Land Is Mine) and two clandestine radio broadcasters (Freedom Radio, Underground).

Compared with all other film noirs, the most gruesome acts of violence are committed in this type of spy noir. When women refuse to obey, fascists beat them (Above Suspicion, Underground), whip them (Hitler’s Children, Women in Bondage) or pull out their fingernails (Behind the Rising Sun).

Joan Crawford is bound and beaten in Above Suspicion.

Joan Crawford is bound and beaten in Above Suspicion.

Kaaren Verne is beaten up in Underground. (A violinist in a Berlin cafe, she is also threatened with having her fingers broken, one by one.)

Kaaren Verne is beaten up in Underground. (A violinist in a Berlin cafe, she is also threatened with having her fingers broken, one by one.)

Bonita Granville, blouse torn open to expose her back, is flogged in Hitler’s Children.

Bonita Granville, blouse torn open to expose her back, is flogged in Hitler’s Children.

Nancy Kelly is whipped in Women in Bondage.

Nancy Kelly is whipped in Women in Bondage.

Gloria Holden’s fingernails are pulled out in Behind the Rising Sun.

Gloria Holden’s fingernails are pulled out in Behind the Rising Sun.

Females die keeping mum. Along with the shooting of the hotel maid (Anne Baxter) in Five Graves to Cairo (see Note 1), here are two other examples.

In Betrayal from the East, Peggy Harrison (Nancy Kelly) is in US Army Intelligence. As part of her “job” she has been the “girlfriend” of “a leading Nazi agent,” Kurt Guenther (Roland Varno). A Japanese fifth columnist, Mr. Araki (Hu Ho Chang), cannot get her to reveal her true identity and her connection with Eddie Carter (Lee Tracy), a civilian undercover operative helping the Army protect the Panama Canal. Guenther shoves Harrison into a steam room and raises the heat, expecting her to talk. She doesn’t, and her last words are, “Eddie, Eddie.”

In Confidential Agent, Else (Wanda Hendrix) is a 14-year old cleaning girl in a London hotel. When she refuses to reveal the location of papers critical to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, the pro-Fascist hotel manager, Mrs. Melandez (Katina Paxinou), pushes her out of an upper story window. Else’s scream lasts six seconds. Contreras (Peter Lorre), an accomplice to her death, later tells the “confidential agent,” Luis Denard (Charles Boyer), that Melandez said, “It was only one girl out of thousands. They die every day. It’s war.”

Axis pilots bomb and strafe defenseless populations, mass murdering women and children inside cities (North of Shanghai, Bombs Over Burma) or on country roads (Paris Calling, China). Occupying forces threaten local civilians with death unless resistance fighters give themselves up. If the commoners refuse to betray their compatriots, they will be slaughtered (Hangmen Also Die!, Uncertain Glory).

In Hangmen Also Die!, an assassin (Brian Donlevy) is chased by Nazis in one of two spy noirs about the killing of Reinhard Heydrich.

In Hangmen Also Die!, an assassin (Brian Donlevy) is chased by Nazis in one of two spy noirs about the killing of Reinhard Heydrich.

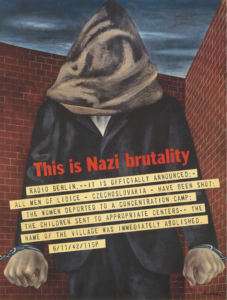

In retaliation for the murder of Reinhard Heydrich, the “Hangman of Prague,” near Lidice, Czechoslovakia (May 1942), a Nazi officer issues the following “proclamation” to the town’s inhabitants (Hitler’s Madman).13

“Upon orders of our Führer, the town of Lidice will be razed to the ground – her name to eradicated from every signpost, from all maps of the country and from the memory of all mankind – an atonement for the assassination of his excellency Reinhard Heydrich, Protector of Czechoslovakia. All male inhabitants over 16 years of age will be shot; all women interned in concentration camps; all children will be taken from their mothers and placed in correctional institutions; all livestock will be confiscated for the use by the German army. Attention! Fire the houses! Load the trucks! The executions will take place in the churchyard!”

The orders are carried out: the children are pulled away from their mothers; the women are herded on trucks; and the men are marched to a churchyard, where, while they defiantly sing, they are mowed down.

As in Hitler’s Madman, the most gruesome extermination of innocent civilians is by machine guns (China Girl, Tomorrow We Live, Assignment in Brittany, Hostages).

As in Hitler’s Madman, the most gruesome extermination of innocent civilians is by machine guns (China Girl, Tomorrow We Live, Assignment in Brittany, Hostages).

This is Nazi Brutality (1942) was Ben Shahn’s response to the massacre in Lidice, an offset lithograph poster issued by the US Office of War information.

This is Nazi Brutality (1942) was Ben Shahn’s response to the massacre in Lidice, an offset lithograph poster issued by the US Office of War information.

In other spy noirs, firing squads use rifles. After a French woman (Annabella) informs on a good spy, her parents are shot nonetheless (Tonight We Raid Calais). Five boys admit to a Nazi officer that they helped their schoolmistress escape to join the Yugoslavian partisans. The officer tells one of the students, “I’m going to plant a picture in your mind you’ll carry with you all your life.” The youth must watch as his four friends, plus two randomly picked classmates, are summarily executed in the schoolyard (Undercover).

In The Conspirators, a Dutch resistance fighter (Paul Henreid) tells the following story to several Portuguese in a fishing village:

“I was a schoolteacher in Holland. One morning I was writing a lesson on the blackboard – the Nazis came. They came so suddenly I didn’t have time to know what was happening. There were dead people in the streets, and a military band in the square. One of my pupils, a 14-year old boy, jumped to the blackboard and wrote three words it. ‘Long live liberty.’ A German officer shot that boy and arrested me. He arrested me for teaching dangerous thoughts. But I escaped. Those who escape learn to hide, to do without food, without sleep, without rest. They also learn to throw bombs and cut wires, to blow up trains and destroy power stations. Many times a message is left, so that when the Germans reach the scene, all they find is a wreck and a piece of paper with three words on it – the words that 14-year old boy wrote on the blackboard. ‘Long live liberty.'”

The following scene in Tonight We Raid Calais is presented in two parts. In the first, a French woman (Annabella) reveals a military secret to a Nazi Captain (Richard Derr) because he promises to spare the lives of her parents. Four other village women, Resistance fighters, are preparing Molotov cocktails. The fires they set off will burn the fields that surround a munitions factory. The flames will guide RAF planes to bomb the correct buildings, instead of decoys the Germans have constructed.

The second part indicates why the woman changes her mind about the war and converts to supporting Allied cause.

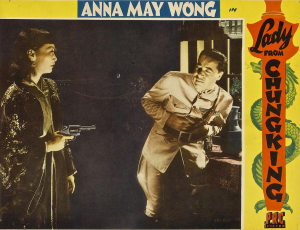

In Lady from Chungking, the Japanese “overseer” of Chinese “coolies” in a rice field is found murdered. A general (Harold Huber) wants a firing squad to kill everyone who was working in the field. The secret leader of the Chinese resistance (Anna May Wong), with her beauty and cultured manners, has won the general’s love and respect. As he is about to order the first execution, she suggests that he should spare the young workers or else his own troops will have to toil in the rice fields. Although she saves these lives, the elderly cannot escape the general’s retribution. He says, “Let the young ones see that for their crimes their fathers will pay.” She sits and watches, barely holding back her tears, as the village’s old men are shot, “two at a time; it saves ammunition.”

In spy noirs about resistance fighters, there are many female victims of sexual assault. Teenage girls commit suicide after they are raped (Hotel Imperial, Pastor Hall, China) – or beforehand. In Hitler’s Madman, the “Hangman” (John Carradine) chooses young Czech coeds to be sent to the Russian front “to entertain our courageous German soldiers.” Before one of them can “be examined like cattle,” she jumps off a window ledge several stories high.

In Pastor Hall, a 14-year old German girl (Lina Barrie) is raped and abandoned by a Nazi youth leader. Now pregnant, she overhears that her neighbors scorn her. Moments later, she hangs herself.

In Pastor Hall, a 14-year old German girl (Lina Barrie) is raped and abandoned by a Nazi youth leader. Now pregnant, she overhears that her neighbors scorn her. Moments later, she hangs herself.

In Behind the Rising Sun, a Japanese soldier grabs a Chinese boy from his mother and throws him up in the air so that he will fall on a bayonet. In another scene, one soldier removes a baby from its mother, and two others take her back inside her house and shut the door. Above the screaming infant there is a flyer that says, “PROCLAMATION! ALL women in this area will remain at home until further notice. All women will welcome all Japanese soldiers.”

In Edge of Darkness, a Norwegian village is under the jackboot of a Nazi battalion and a merciless commandant (Helmut Dantine). To forestall a revolt, he issues an order, “All restrictions on our troops are to be lifted. They are free to do in this town as they please.” After a soldier rapes a woman (Ann Sheridan), who is a leader of the underground, her father (Walter Huston) kills the rapist. The woman, her father and the others in the resistance are ordered to dig their own mass grave. Just before they are shot, the townsfolk launch the revolt. When the mutual slaughter is over, the village is depopulated – the corpses of hundreds of Nazis and Norwegians lie in heaps wherever the camera pans. With his troops all dead, the commandant blows out his brains. A handful of locals who survive, including the raped woman, continue their anti-fascist fight as guerrillas based in forests.

Rape isn’t the only way females are sexually violated. In Women in Bondage, according to “the principle guiding the life and existence of all Hitler women and Hitler girls…children and ever more children will make the Reich eternal.” A girl (Nancy Kelly) in this film who won’t submit to assembly line reproduction is executed.

At a Prague restaurant next to the Vitava River in Hostages, a drunken and sobbing Nazi lieutenant (Hans Conreid) says to a washroom attendant, “It’s more than a man can bear. The girl I was to marry – they’ve sent her to a breeding colony.” Once he is alone, the officer drowns himself.

In Hitler’s Children, the “breeding colony” is called the “rest home” at a “labor camp.” In fact, the Nazis’s own term was Lebensborn (fount or fountain of life).14 A young woman (Bonita Granville) gives a tour to her former professor Nichols (Kent Smith). A Nazi lieutenant (Tim Holt) says that the young females “are drafted to serve just as men are in the army. And they serve just as proudly.” The woman, who has yet to reveal her opposition to the New Order, adds, “They work hard and live simply to fit them for their duties to the state. The only recreation provided is the Saturday night dance. There, lovers may meet and decide to share the experience that makes them worthy of the Führer.” The scene continues below.

Before the US entered the war, the role of Nazi women to birth future soldiers wasn’t dealt with so critically, but instead discreetly. In one of the earliest US spy noirs, Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), the American Third Reich leader asks a pubescent girl at a Nazi youth rally, “What are the ideals of German womanhood?” She answers, “To be of service to our Führer. To be the custodian of our children until they shall be called unto arms.”

In Hitler’s Children, as they look down at a large surgery room, a Nazi colonel (Otto Kruger) says the following to the professor.

“This, professor, is a most unusual clinic. In fact, the most unusual. One of the finest of its kind in the world. You are observing what is probably the most progressive medical advance ever attempted by any government. All these patients are women, women who are unfit to have children. They are being sterilized…We are building a new Germany, a strong Germany. There is no room for sick and the weak and the unstable…Of course, although the majority of cases are the weak and the unstable, our doctors operate for a number of other reasons. Would you believe it, professor, they range from eliminating hereditary color blindness to dangerous political thinking. In political cases it makes the woman much quieter, more reasonable. It is sometimes much kinder than putting a woman in a concentration camp.”

The lieutenant, dedicated to Hitler since his youth, becomes so revolted by his superior’s cold-blooded description of the practices at the “Fräulein Clinic” that he turns against the Third Reich. In the climax of Hitler’s Children, he is shot as a traitor; immediately afterwards, the woman he has loved since they were teenagers, is killed for her own disloyalty.

The lieutenant, dedicated to Hitler since his youth, becomes so revolted by his superior’s cold-blooded description of the practices at the “Fräulein Clinic” that he turns against the Third Reich. In the climax of Hitler’s Children, he is shot as a traitor; immediately afterwards, the woman he has loved since they were teenagers, is killed for her own disloyalty.

In The Silver Fleet, a wife (Googie Withers) locks her husband (Ralph Richardson) out of their bedroom because she believes he is a Nazi collaborator. Later, she reads his diary and discovers how he made himself a martyr for the Dutch resistance.

In The Silver Fleet, a wife (Googie Withers) locks her husband (Ralph Richardson) out of their bedroom because she believes he is a Nazi collaborator. Later, she reads his diary and discovers how he made himself a martyr for the Dutch resistance.

In the first example below the resistance is by an English village against an invasion of Nazi paratroopers; in the second it is by a Dutchman who designs a U-boat; and in the other four examples the central character is a woman.

UK: Went the Day Well?, The Silver Fleet, The Lisbon Story

US: Conspiracy, Desperate Journey, First Comes Courage

IV. Fifth Columnists

The key secret activity is by fifth columnists, who are, generally speaking, a group of people that, overtly or covertly, act in support of an enemy of their own country.15 In spy noirs, every ring of fifth columnists is mostly male, but the ringleader is often a woman.

In Secret Command, an undercover federal agent, Sam Gallagher (Pat O’Brien), has a partner, Jill McGann (Carole Landis), who pretends to be his wife. Their mission is to bust up a ring of pro-Nazi fifth columnists who aim at sabotaging the shipyard where Gallagher’s brother (Chester Morris) is the foreman. In the climax, Gallagher hunts the ringleader in the fog on the ship that is set to explode and blow up the shipyard.

In Secret Command, an undercover federal agent, Sam Gallagher (Pat O’Brien), has a partner, Jill McGann (Carole Landis), who pretends to be his wife. Their mission is to bust up a ring of pro-Nazi fifth columnists who aim at sabotaging the shipyard where Gallagher’s brother (Chester Morris) is the foreman. In the climax, Gallagher hunts the ringleader in the fog on the ship that is set to explode and blow up the shipyard.

In Tampico, an American ship captain (Edward G. Robinson) believes that the approaching woman is not only a Nazi agent but also his wife.

In Tampico, an American ship captain (Edward G. Robinson) believes that the approaching woman is not only a Nazi agent but also his wife.

Literally, one of the darkest scenes in spy noir is the climax of Unpublished Story. Two journalists, Bob Randall and Carol Bennett (Richard Greene and Valerie Hobson) are working together to expose a “pacifist” organization as a front group for the Nazis. One member of the “People for Peace,” Trapes (Frederick Cooper), becomes disillusioned and sends Bennett a letter denouncing it. So naïve is Trapes that he tells what he has done to the fascists. Just before Randall and Bennett arrive at a London train station, British counter-intelligence agents set up Trapes as the bait to lure the Nazis out into the open. Their plan is that Trapes won’t be killed, but the Nazis will be captured. The title of the film derives from final scene when the chief of the British agents (Basil Radford) tells the reporters that, in “the public interest” (i.e., to prevent the public from being frightened to learn that Nazi agents have been at large on home soil), their scoop can’t be printed.

A film’s central characters may be the opponents of fifth columnists – good civilians or good government agents. For example, when fifth columnists commit a crime that the police blame on an innocent man, the lead roles belong to the accused and a woman who is critical to proving he isn’t guilty. In the WWII era, there are many crime noirs featuring a hunted man whose “ally” is a woman with a job.16 However, this plot “formula” is even more frequent in spy noirs: Man Hunt, Meet Boston Blackie, Pacific Blackout, All Through the Night, Fly-By-Night, Little Tokyo, U.S.A., Saboteur, This Gun for Hire, The Gorilla Man, Hangmen Also Die!, Journey Into Fear, The Conspirators, Ministry of Fear, Waterfront. For a full exposition of the hunted man and his working class ally in the WWII era in both spy noirs and crime noirs, see the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar.

While it may be the rule that British and American authorities only round up and put away actual fifth columnists, there is an infamous and historically true exception. At the end of Little Tokyo, U.S.A., we see documentary footage of Japanese in Los Angeles, their belongings piled high on sidewalks, waiting to be transported to internment camps. A newspaper headline says, “LAST JAPS LEAVE L.A. AREA TODAY – Military Area Cleared of Possible Saboteurs.” With a long line of buses on the move in the background, a female radio announcer (Brenda Joyce) faces us and speaks into her microphone, “And so, in the interest of national safety, all Japanese, whether citizens or not, are being evacuated from strategic military zones on the Pacific coast. Unfortunately, in time of war, the loyal must suffer inconvenience with the disloyal.” Additional justification for the internment is given earlier in the film when the Japanese-American head of “the operations in southern California” (Harold Huber) says to an American fifth columnist (Donald Douglass), “Mass evacuation, as you know, will defeat our plan of operation here.”17

In the first two US examples below, the hero is a civilian (medical intern, aircraft worker), and in the third he is a secret federal operator (shipyard worker). Each man successfully smashes a ring of fifth columnists with the close aid of a woman – an undercover UK and US agent, respectively, in the first and third films, and a billboard model in the second.

UK: Traitor Spy, Spies of the Air, The Next of Kin

US: Dangerously They Live, Saboteur, Secret Command

V. Converted to the Allied Cause

In this plot type a man or a woman is at first either unconcerned with or opposed to the UK or US winning the war. Due to their subsequent experiences, they change their minds and take sides against Germany or Japan.18 At the end of the film they may still be fighting or they may have sacrificed their lives.

In Four Sons, an anti-Nazi in Germany (Don Ameche) is betrayed by his sister-in-law (Mary Beth Hughes). Much later, realizing she has supported the wrong side, she leaves Germany to keep her son from being called up to the Wehrmacht.

In Four Sons, an anti-Nazi in Germany (Don Ameche) is betrayed by his sister-in-law (Mary Beth Hughes). Much later, realizing she has supported the wrong side, she leaves Germany to keep her son from being called up to the Wehrmacht.

In Tonight We Raid Calais, before her conversion, it is especially poignant why a local woman (Annabella) not only refuses to assist a British commando with his mission but is willing to betray him to the Nazis. Her brother was among 1297 servicemen killed on 3 July 1940, when the British bombed the French fleet at the port of Mers-el-Kébir, outside Oran, Algeria.19 Since her brother’s wife is also dead, she has assumed responsibility for raising his orphaned son.

Two older men who once believed, respectively, in the New Order in Germany and Japan, come to realize it is abhorrent. In the climax, one faces execution (Address Unknown), and the other commits hara-kiri (Behind the Rising Sun). Crucial to each man’s conversion is the tragedy that occurs to a young woman who was going to marry the man’s son.

In Address Unknown, the fiancé (K. T. Stevens) is to star in a performance of the Passion Play in Berlin. An agent of the Department of Censorship orders certain lines of Christianity to be deleted, such as, “The meek shall inherit the earth.” He warns, “Disobedience is treason.” When the woman speaks the forbidden words, the agent stops the show and reveals her secret to the full house – she is a Jew. In the scene below, the revelation whips the audience into a frenzy, and it charges the stage after her and chases her through the streets. (At the end of the scene, note the J painted on the door.)

With the crowd hunting her in Berlin, she flees from the city. Closely pursued by Nazi police over marshlands and through woods, she reaches the home of the man who once was to be her father-in-law (Paul Lukas). After he refuses to help her so that the Nazis can kill her (note her bloody handprint inside his front door), he tries to prevent his wife (Mady Christians) from crying out her name, “Griselle,” a second time.

In Behind the Rising Sun, the father (J. Carrol Naish) has a son (Tom Neal) who is a Japanese army colonel. He and his fiancé (Margo) accidentally discover that her parents have sold “little sister” to Yoshiwara, the historic red light district in Tokyo. At first the colonel is proud of the girl for making “a wonderful sacrifice.” Then, war is announced between Japan and the US. As the woman searches for her sister to “buy her back,” she is arrested on trumped up charges of being a spy. Her crime is friendship with three Americans (Robert Ryan, Gloria Holden, Donald Douglas), who are also accused of espionage. To get confessions, they are tortured – one of them to death (Ryan). At a kangaroo court, the colonel renounces his fiancé, and his testimony seems to seal her fate for capital punishment.

In the two UK examples below, the converted is first a French working-class woman and then one who is Irish; in the first US example, it is a female German aristocrat; and then in the next two examples, it is a male American ex-patriot entrepreneur (first a nightclub owner and then a freelance pilot).

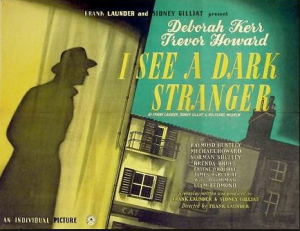

UK: Secret Mission, I See a Dark Stranger

US: Escape, Casablanca, China Girl

Three Key Aspects of Spy Noir

I. International from the Start

Spy noirs, from their first years, were released both in Britain and the United States. Spy noir begins as international and, therefore, film noir shouldn’t be defined as uniquely American. (See Note 3 for filmographies of early French film noirs.)

II. Spy Noirs Begin before 1940, Principally in Great Britain

There is no consensus on the time frame of film noir. While it was once customary to start “the classic period” in 1940, there are filmographies with film noirs from the 1930s. For example, John Grant includes UK and US film noirs from the 1930s (plus more released in other countries in that decade). Michael F. Keaney’s earliest British film noirs are in the late 1930s; and there are British film noirs throughout the 1930s in Robert Murphy’s list.20

As my tables indicate, in 1939, the year WWII begins in Europe, the release of spy noirs takes off in Britain and, especially, America.

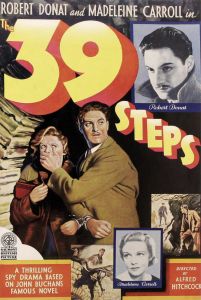

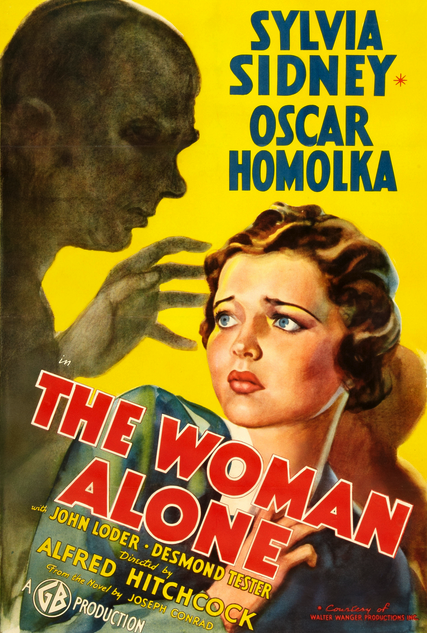

John Grant and Robert Murphy are the only historians whose filmographies include pre-1939 spy noirs, and all of them are all British. They both name The Man Who Knew Too Much and Sabotage (aka The Woman Alone), and Murphy adds Dark Journey and Strange Boarders.

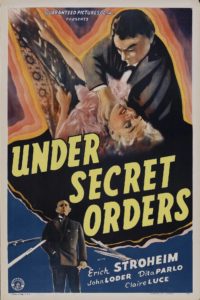

I include seven more from the UK: The Crouching Beast, The 39 Steps, Secret Agent, The Secret of Stamboul (aka The Spy in White), Bulldog Drummond at Bay, I Married a Spy (aka Secret Lives), Under Secret Orders.

I include seven more from the UK: The Crouching Beast, The 39 Steps, Secret Agent, The Secret of Stamboul (aka The Spy in White), Bulldog Drummond at Bay, I Married a Spy (aka Secret Lives), Under Secret Orders.

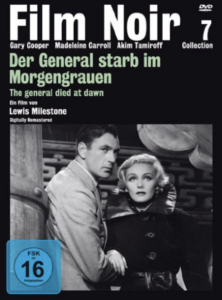

I also cite the first three pre-1939 US spy noirs: The General Died at Dawn, International Settlement and Blockade.

III. Greater Gender Equality

In crime noir, women have been repeatedly categorized in specific and limited ways. For example, Jon Tuska’s opinion is representative.

“There are two basic kinds of women in film noir, with a third, subsidiary type only occasionally present. The two basic types are the femme fatales and the loving wives and mothers…The third type of noir woman is the beautiful neurotic. She is not found as often as the femme fatale, but when she is, as in Sorry, Wrong Number (Paramount, 1948), she is still the primum mobile which brings both herself and the noir male protagonist to catastrophe.”21

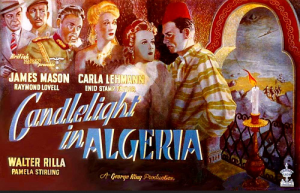

Unlike women in crime noirs, women in spy noirs play nearly all the same roles as men. There are female airplane pilots, newspaper reporters, radio broadcasters, underground resistance fighters, fifth columnist ringleaders, good and bad secret agents, and so on. In Candlelight in Algeria, this is the way a woman (Carla Lehmann) expresses her self-consciousness that women are the equals of men, “The only job a man can do that a woman can’t is to grow a mustache.”

The greater gender equality in spy noirs is due to its historical period, the WWII era. British and American women markedly contributed on the home front and in the armed forces. With increased economic and social independence, women were a different kind of movie audience than they had ever been before. Accordingly, the studios responded with plots and characters more appealing to and appropriate for these self-confident females.22

The female war worker in Laura Knight’s painting, Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring (1943), was Britain’s Rosie the Riveter.22

The female war worker in Laura Knight’s painting, Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring (1943), was Britain’s Rosie the Riveter.22

A woman shows how the resistance struggle is her highest priority when she doesn’t accompany a man back to America or Britain, where their love affair could safely continue: Cloak and Dagger, Conspiracy, Desperate Journey, Escape, First Comes Courage, The Lisbon Story, Reunion in France, Secret Mission, Storm Over Lisbon, Tonight We Raid Calais. At the end of the film, she remains where she is to keep on with the “secret war” against the Nazis.

For example, in the conclusion of Tonight We Raid Calais, the women seen in an earlier clip have succeeded in setting fires around the Germans’ munitions factory, and RAF bombers have destroyed it. One of them (Annabella), now converted to the Allied cause after she witnessed Nazis gun down her parents, asks a British commando (John Sutton) to take her orphaned nephew with him to England. She will stay behind with the other women.

In Desperate Journey, a woman in the anti-fascist underground (Nancy Coleman), helps RAF crewmen escape from Germany after their plane is shot down. The squadron leader (Errol Flynn) wants her to come with his team to Britain. She declines. He says, “But you’ve done your share and more.” She says, “No one’s share will be done until the war is over. There will be other men, from the prison camps, the concentration camps, the conquered countries. It’s our job – the job of the underground – to return them to the fight. We must all do our work before we can go back to doing what we like.”

In Desperate Journey, a woman in the anti-fascist underground (Nancy Coleman), helps RAF crewmen escape from Germany after their plane is shot down. The squadron leader (Errol Flynn) wants her to come with his team to Britain. She declines. He says, “But you’ve done your share and more.” She says, “No one’s share will be done until the war is over. There will be other men, from the prison camps, the concentration camps, the conquered countries. It’s our job – the job of the underground – to return them to the fight. We must all do our work before we can go back to doing what we like.”

As was actually happening between couples in the UK and the US, romance is put on hold for the duration. In Escape, a countess (Norma Shearer) insists on staying in Germany so that her former lover, a Wehrmacht general (Conrad Veidt), cannot “torture” two local residents who enabled her new American lover (Robert Taylor) to get across the border. She promises to meet the Yank later “on 57th. Street.”

The namesake of Joan of Paris, knowing it means her death, stays behind to prevent Nazis from capturing her lover and his four RAF crewmen.

In Joan of Paris, the cleverness and sacrifice of a woman (Michèle Morgan) saves British airmen (featuring Paul Henreid and Alan Ladd) from a Gestapo chief (Laird Cregar) and his squad of soldiers.

In Joan of Paris, the cleverness and sacrifice of a woman (Michèle Morgan) saves British airmen (featuring Paul Henreid and Alan Ladd) from a Gestapo chief (Laird Cregar) and his squad of soldiers.

Behind the Rising Sun presents quite different circumstances but with a similar outcome. Three innocent people are about to be executed as spies on trumped up charges: two Americans in love with each other, a newspaperwoman (Gloria Holden) and an engineer (Donald Douglas), and the engineer’s Japanese secretary (Margo). While Tokyo is being bombed by US warplanes, the three are rescued and driven out of the city in the limousine of their friend (J. Carrol Naish), who is a government cabinet minister. The plan is for them to be flown to America. Abruptly, Margo asks the driver to stop the car. Before she gets out, she says to Holden and Douglas, “All my life I’ve wanted to go to America. But that must wait now. My place is here. I know that there isn’t much that I can do alone, but someday perhaps we will be delivered by those who are free, and it will be important that there are some of us here who understand the world outside and a few outside who understand Japan – the Japan that is yet to be born.”

In spy noirs, there are not only true romances but also false ones. Whereas men don’t do it, women go under covers and sleep with the enemy. When she is a wife, she outlives her husband and then has real love with another man, who is a hero on her side (Paris Calling, First Comes Courage, The Man from Morocco, Notorious). When she is a mistress in later spy noirs, the man kills her in revenge for her duplicity (Lady from Chungking, Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, Edge of Darkness). In The Spy in Black, a female British secret agent (Valerie Hobson) pretends to be a German spy. She tells a real German spy (Conrad Veidt) that, in order to make plans to destroy a British fleet, they are getting help from “a British naval officer with a grudge against the service.” He has no objection or regret when she says the traitor’s “rather high” price was paid by Germany “and me.” (For an in-depth analysis, see the page The Spy in Black.)

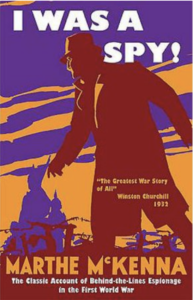

Before the films named above were released, Madeleine Carroll had already been pimped twice. In the UK spy film, I Was a Spy, Carroll, a Belgian nurse living under German occupation during WWI, is urged by her lover and espionage partner (Herbert Marshall) to accept the offer to take a trip and thereby sleep with the town Kommandant (Conrad Veidt) in order to get him to reveal classified information. Once Veidt obtains evidence that Carroll is a spy, despite his own unhappiness, since he also loves her, he follows his duty, arrests her and demands that a military tribunal have her executed. Instead, her life is spared when Marshall sacrifices his own, and she is imprisoned until Belgium is liberated. Published a year earlier, in 1932, I Was a Spy! is the title of the memoirs of the real undercover life of Marthe Cnockaert, whose deception was so successful that, before being exposed, she was awarded Germany’s Iron Cross. The film opens with this statement, excerpted from the book’s Foreword:

Before the films named above were released, Madeleine Carroll had already been pimped twice. In the UK spy film, I Was a Spy, Carroll, a Belgian nurse living under German occupation during WWI, is urged by her lover and espionage partner (Herbert Marshall) to accept the offer to take a trip and thereby sleep with the town Kommandant (Conrad Veidt) in order to get him to reveal classified information. Once Veidt obtains evidence that Carroll is a spy, despite his own unhappiness, since he also loves her, he follows his duty, arrests her and demands that a military tribunal have her executed. Instead, her life is spared when Marshall sacrifices his own, and she is imprisoned until Belgium is liberated. Published a year earlier, in 1932, I Was a Spy! is the title of the memoirs of the real undercover life of Marthe Cnockaert, whose deception was so successful that, before being exposed, she was awarded Germany’s Iron Cross. The film opens with this statement, excerpted from the book’s Foreword:

“Self-preservation has forced States and armies in every age to exact the penalty of death from a spy. A Secret Service Agent who is not actuated by any sordid motive, but inspired by patriotism, and ready to pay the well-known forfeit, deserves respect and honour from those he serves so faithfully. Marthe Cnockaert fulfilled in every respect the conditions which make the terrible profession of a spy dignified and honourable.

“Rt. Hon. Winston S. Churchill, P.C., C.H., M.P. (Secretary of State for War, 1918-1921)”

In The General Died at Dawn, Carroll’s father (Porter Hall) whines that because he is dying, he wants money to return to America for his final “six months.” Browbeaten and guilt-tripped, Carroll obeys her father’s wishes and seduces Gary Cooper into taking a train (which he knows is dangerous) instead of a plane (which would be much safer). What is the difference? On the train he is vulnerable to being robbed of a belt that holds a lot of money raised from Chinese peasants to buy guns and ammunition to repel a warlord, General Yang (Akim Tamiroff), who is oppressing (and killing) them. Carroll understands, according to her father’s plan, Yang is going to board the train, take away the money belt from Cooper, and then kill him. Nursing a hatred of Carroll (since losing the money means he failed the peasants who had raised it), Cooper manages to escape from Tamiroff and his soldiers and goes after Carroll to recover the belt. Carroll, meanwhile, despairs of her role in helping her father. By the end of The General Died at Dawn, not only Yang but also her father are dead, and Carroll and Cooper have reconciled and are romantically coupled. Released in October 1936, this film is the first US spy noir, and Carroll is the first femme fatale in all of film noir (whether from France, the UK or the US). She isn’t a “hard” femme fatale, but a “soft” one. For an explanation about the soft femme fatale vs. hard femme fatale, see the page International Lady.

Besides I Was a Spy, there are three spy noirs, based on actual events, about women in espionage: Under Secret Orders, Nurse Edith Cavell and Paris Underground.

For an in-depth analysis of the three 1930s films based on the WWI German secret agent, Elsbeth Schragmüller, see the page Under Secret Orders. In this film, Dita Parlo is the first “hard” femme fatale in all of film noir (from France, the UK or the US).

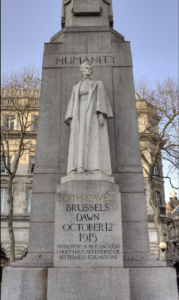

Nurse Edith Cavell recounts the true story of a British nurse, played by Anna Neagle. She and three female friends help “about 200” British soldiers escape from occupied Belgium into the Netherlands. All four women are arrested and tried, but only Cavell is sentenced to death. As it actually happened, at dawn at her prison in Brussels on October 12, 1915, she is shot by a German firing squad. The next scene in 1919, is Cavell’s funeral service in Westminster Abbey. Her three friends are present. The film ends with Cavell’s last words, “Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness toward anyone,” which are inscribed on her memorial in London.

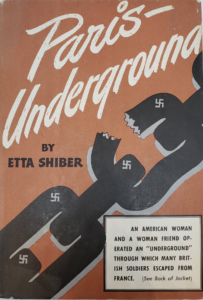

Constance Bennett produced and stars in Paris Underground, which draws on Etta Shiber’s best-selling memoir of the same name (but released in the UK as Madame Pimpernel). Until Shiber and her female confederate were captured and imprisoned by the Nazis, they had helped over 150 English soldiers, left behind in France after its surrender, escape to freedom. At the end of the film, Bennett says that she and her friend (Gracie Fields) rescued “259 British and American airmen.” The book was published in 1943, whereas the film was released after the war in October 1945. This suggests how the final scene was invented, in which Bennett and Fields are shown at an outdoor ceremony in Paris where they are “awarded for exceptional valor and courage” the medal for the Order of Liberation from the French Republic.

Constance Bennett produced and stars in Paris Underground, which draws on Etta Shiber’s best-selling memoir of the same name (but released in the UK as Madame Pimpernel). Until Shiber and her female confederate were captured and imprisoned by the Nazis, they had helped over 150 English soldiers, left behind in France after its surrender, escape to freedom. At the end of the film, Bennett says that she and her friend (Gracie Fields) rescued “259 British and American airmen.” The book was published in 1943, whereas the film was released after the war in October 1945. This suggests how the final scene was invented, in which Bennett and Fields are shown at an outdoor ceremony in Paris where they are “awarded for exceptional valor and courage” the medal for the Order of Liberation from the French Republic.

Spy Noirs Contradict Film Historians’ Conceptions of a Unitary “Asia”

In what follows, I examine discussions by two historians who treat “Asia” in film noir as a single geographical entity and, consequently, as inhabited by people without differences, such as political and military. However, spy noirs (as well as other spy films) contradict this treatment. These historians fail to recognize that during the WWII era Hollywood represented the “East” not as unitary but as binary. That is, there were consistent positive portrayals of China and the Chinese versus extreme negative depictions of Japan and the Japanese.

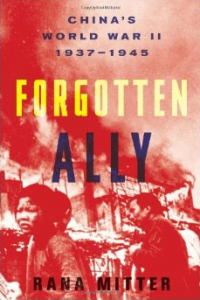

As Rana Mitter explains in Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945, there has been a loss to the public’s historic memory of China’s war with Japan. “Most Westerners have scarcely heard of the bombing of Chongqing. Even for the Chinese themselves, the events were concealed for decades. Yet they are part of one of the great stories of the Second World War, and perhaps the least known. For decades, our understanding of that global conflict has failed to give a proper account of the role of China. If China was considered at all, it was as a minor player, a bit-part actor in a war where the United States, Soviet Union, and Britain played much more significant roles. Yet China was the first country to face the onslaught of the Axis Powers in 1937, two years before Britain and France, and four years before the United States. And after Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941), one American goal was to “keep China in the war.” By holding down large numbers of Japanese troops on the mainland, China was an important part of the overall Allied strategy.”24

As Rana Mitter explains in Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945, there has been a loss to the public’s historic memory of China’s war with Japan. “Most Westerners have scarcely heard of the bombing of Chongqing. Even for the Chinese themselves, the events were concealed for decades. Yet they are part of one of the great stories of the Second World War, and perhaps the least known. For decades, our understanding of that global conflict has failed to give a proper account of the role of China. If China was considered at all, it was as a minor player, a bit-part actor in a war where the United States, Soviet Union, and Britain played much more significant roles. Yet China was the first country to face the onslaught of the Axis Powers in 1937, two years before Britain and France, and four years before the United States. And after Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941), one American goal was to “keep China in the war.” By holding down large numbers of Japanese troops on the mainland, China was an important part of the overall Allied strategy.”24

Spy noirs about China include all five of the plot types that I describe above. They feature the Japanese armed forces bombing, machine-gunning and raping Chinese civilians. The opening of China Girl says, “The Jap invaders bring the New Order into China – with bullets.” Spy noirs in which the Japanese viciously assault Chinese cities include: Bombs Over Burma (Chongqing), China (Meiki), China Girl (Luichow, Kunming), International Settlement, and North of Shanghai (Shanghai).

In fact, the second US spy noir, International Settlement was also, according to Daily Variety, “The first feature picture dealing with the bombing and military devastation of Shanghai ready for release…[and]…News clips are effectively inserted with the studio material.”25

Today, Americans are unlikely to know either that Chongqing was China’s wartime capital or the importance (and perils) of supply trucks traveling there. In the WWII era, Hollywood was a source of this information. For example, Burma Convoy opens with a “Foreword” that scrolls on the screen.

“Through the teeming heart of Asia, halfway between Rangoon and Shanghai, twists the hand-hewn Burma Road, lifeline for the embattled Army of China, headquartered at Chungking. Over this seven hundred mile highway roars a stream of trucks – hell-drivers at their wheels – trucks loaded with fuel, munitions, guns – blood and sinew of the defenders of the ancient soil of China.”

It was vital to Japan to close the Burma Road, which it did in April 1942. Besides Burma Convoy, films about the “lifeline” to sustain China’s resistance include: A Yank on the Burma Road, Bombs Over Burma, Half Way to Shanghai, China Girl, Night Plane from Chungking.

For a documentary about the British-Indian army effort to liberate Burma from Japanese control, see Prelude to Victory: Burma, 1942. The description on YouTube is:

“In late 1941 and early 1942 the Imperial Japanese Army swept through the Asia-Pacific region like a wildfire. The Allies appeared powerless to stop them. With the British Army in Asia reeling, and pushed back to the frontier of India, something had to be done to stem the tide. “Prelude to Victory: Burma, 1942” provides context for Field Marshal William J. Slim and the 14th Army’s struggle to retake Burma from the Japanese.”

In most spy noirs about China, Anglo-Americans are the lead characters. Asian Americans, however, aren’t limited to being villains. For example, Anna May Wong, Hollywood’s first Chinese-American film star, is the hero in Bombs Over Burma and Lady from Chungking. Several Asian-American men are frequently cast in roles, varying from film to film, in which they are either good Chinese or bad Japanese. These actors include Korean-American Philip Ahn and Chinese-Americans Richard Loo, Keye Luke and Victor Sen Yung, who are pictured below in sequence.

In Lady from Chungking, Anna Mae Wong kills the Japanese General (Harold Huber) who heads the occupation of her village. Before her execution, she says, “You cannot kill me. You cannot kill China!”

In Lady from Chungking, Anna Mae Wong kills the Japanese General (Harold Huber) who heads the occupation of her village. Before her execution, she says, “You cannot kill me. You cannot kill China!”

In the sub-chapter, “Asia,” of his book, Nothing More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts, James Naremore inaccurately sees a unitary Asia as represented in film noir. Furthermore, the basis of his error is that he considers film noir as derived from hardboiled fiction. As I explain below, this is a “myth” of the origins of film noir that spy noirs contribute to debunking.

In the sub-chapter, “Asia,” of his book, Nothing More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts, James Naremore inaccurately sees a unitary Asia as represented in film noir. Furthermore, the basis of his error is that he considers film noir as derived from hardboiled fiction. As I explain below, this is a “myth” of the origins of film noir that spy noirs contribute to debunking.

“The Asian theme [in film noir] can in fact be traced back to Dashiell Hammett’s earliest hard-boiled stories for Black Mask, which are saturated with a low brow Orientalism reminiscent of the Yellow Peril years before and after World War I. In ‘The House on Turk Street,’ the Continental Op encounters a gang of killers led by Tai Choon Tau, a wily Chinese man who wears British clothes and speaks with a refined English accent. According to the Op, ‘The Chinese are a thorough people; when one of them carries a gun he usually carries two or three or more,’ and when he shoots, ‘he keeps on until his gun is empty.’

“…[In 1942, John] Houston filmed Across the Pacific, a [Maltese] Falcon spin-off, in which Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor battle Japanese spies in Panama. This film was, of course, produced during World War II, when images of deceitful and violent Asians from earlier pulp fiction were easily incorporated into anti-Japanese propaganda.”26

What Naremore sees as consistent, from hardboiled fiction to film noir, is how “Asians” are deceitful and violent – first the Chinese in “earlier pulp fiction,” then the Japanese in WWII film noir. Given that Hollywood politically polarized the bad Japanese against the good Chinese in the WWII era, “Asians” aren’t always deceitful and violent. Naremore’s mistake is inherent in his interpretation of film noir. He posits an “affinity” between film noir and “modernism.” His discussion of the latter focuses on literature. Modernist literature, he says, is “masculine.” Thus, film noir derives from a literary tradition exemplified by hardboiled fiction.26 He ignores Hollywood’s representation of the Chinese in the historical context of World War II. Instead, he takes a literary tradition (“hard-boiled stories”) as the basis of a single theme about Asians – they are deceitful and violent – and because film noir is derived from this literature, Naremore concludes that this “Asian theme” was extended (“easily incorporated”) into film noir.

What Naremore sees as consistent, from hardboiled fiction to film noir, is how “Asians” are deceitful and violent – first the Chinese in “earlier pulp fiction,” then the Japanese in WWII film noir. Given that Hollywood politically polarized the bad Japanese against the good Chinese in the WWII era, “Asians” aren’t always deceitful and violent. Naremore’s mistake is inherent in his interpretation of film noir. He posits an “affinity” between film noir and “modernism.” His discussion of the latter focuses on literature. Modernist literature, he says, is “masculine.” Thus, film noir derives from a literary tradition exemplified by hardboiled fiction.26 He ignores Hollywood’s representation of the Chinese in the historical context of World War II. Instead, he takes a literary tradition (“hard-boiled stories”) as the basis of a single theme about Asians – they are deceitful and violent – and because film noir is derived from this literature, Naremore concludes that this “Asian theme” was extended (“easily incorporated”) into film noir.

A related error in treating “Asian ethnicities” as a single collectivity is committed by Dan Flory in his essay, “Ethnicity and Race in American Film Noir,” in the anthology edited by Andrew Spicer and Helen Hanson, A Companion to Film Noir. Flory’s focus in the essay’s subsection, “Ethnicity in Classic Film Noir,” is about different “ethnicities” and “whiteness.” He says:

collectivity is committed by Dan Flory in his essay, “Ethnicity and Race in American Film Noir,” in the anthology edited by Andrew Spicer and Helen Hanson, A Companion to Film Noir. Flory’s focus in the essay’s subsection, “Ethnicity in Classic Film Noir,” is about different “ethnicities” and “whiteness.” He says:

“Issues of ethnicity are often taken up constructively in works of what might be termed ‘progressive noir’ in the classic period, especially in the years immediately after World War II. In some cases the origins of these films are in literature concerning ethnic prejudice itself. Hierarchies of whiteness that determined disadvantages for ‘borderline whites’ in the United States, such as Italians, Greeks, Poles, and Hispanics, play crucial roles in novels and short stories that serve as the foundation of several noir films….”28

Flory says that some ethnicities (such as Italian Americans and Greek Americans) could have a “positive portrayal” in film noir because “US audiences” (i.e., WASP Americans) “now possessed a less restrictive sense of whiteness in the wake of their wartime experiences.”

“During and after World War II, when millions of US citizens were pulled from their neighborhoods, communities and regions to serve in the armed forces or train far from their places of origin, dedication to a common cause and the mixing of diverse individuals instigated a breakdown of ethnic prejudice and greatly expanded people’s sense of who should be included in the category of whiteness.”29

In short, these “hyphenated Americans” benefitted from an “enlargement of whiteness.”

Flory then considers problematic ethnicities.

“Americans of Hispanic descent and Mexican nationals benefitted as well, but in a noticeably reduced fashion. The former were classified as ‘white’ by the armed forces and unstably joined the dominant racial group. Increasing numbers of both Mexican American and Mexican national characters in film noir reflect this uneasy accommodation….30

“Asian ethnicities present a slightly different constellation of problems. Like the status of Hispanic ethnicity, being Chinese, Japanese or some other Asian group proved more difficult to absorb into whiteness. However, as the noir classic period progressed, some positive characterizations of these groups arose, even if that seemed unlikely at the outset. Early in the noir cycle The Shanghai Gesture (Josef von Sternberg, 1941) conveys a sense of moral panic concerning the ‘yellow peril,’ with the film representing decadence as peculiarly ‘Oriental.’ [Alain] Silver and his fellow authors rightly describe the film as ‘nightmarish,’ but they fail to note that the film roots this quality in racist conceptions of the ‘Orient’ as decadent and something to be feared. What counts as the East here, stretches from Persia to Shanghai and represents exotic, forbidden pleasures and illicit desires….”31

What “Shanghai” is Flory talking about? Flory acknowledges the “racist conceptions” at the “root” of Josef von Sternberg’s film. And, it is worth noting, von Sternberg’s “Shanghai” was a “heavily bowdlerized” version of the original in John Colton’s 1918 play, also called, The Shanghai Gesture. From theater to cinema, “Mother God Damn became Mother Gin Sling. The brothel became a casino. Poppy, instead of being a drug-and-booze-addled nympho, became a compulsive gambler.” The Hollywood version eliminates “a scene of a white girl being auctioned off as a sex slave to lascivious Chinese coolies.” (In the play, the seller is Mother God Damn and the girl is her daughter, who grows up to be Poppy.) No wonder that it was a “controversial play, with protests from the Chinese embassy and accusations of morbid racism.”32

At a dinner party in The Shanghai Gesture, Mother” Gin Sling (Ona Munson) surprises tycoon Walter Huston with his dissolute daughter, Poppy (Gene Tierney), before being shocked to learn that she is the other parent.

At a dinner party in The Shanghai Gesture, Mother” Gin Sling (Ona Munson) surprises tycoon Walter Huston with his dissolute daughter, Poppy (Gene Tierney), before being shocked to learn that she is the other parent.

Flory accepts von Sternberg’s “Shanghai” as representative of the “East,” but only “early in the noir cycle” (during WWII). However, the text at the opening of the film denies that this “Shanghai” can be considered part of the real “Orient” at that time.

“Years ago a speck was torn away from the mystery of China and became Shanghai. A distorted mirror of problems that beset the world today, it grew into a refuge for people who wished to live between the lines of laws and customs – a modern Tower of Babel. Neither Chinese, European, British nor American it maintained itself for years in the ever increasing whirlpool of war. It’s (sic) destiny, at present, is in the lap of the Gods – as is the destiny of all cities. Our story has nothing to do with the present.”

Von Sternberg’s decadent “Shanghai” is imaginary and ahistorical because it has “nothing to do with the present.” In the film an Englishman is taking over large swaths of real estate in the city. In fact, the Japanese had invaded the actual city in 1932, and they didn’t wrest full control from the Chinese until three weeks before the release of the film (December 25, 1941). This Shanghai, the one that was under siege by the Japanese, can be found in film noir – in spy noir. For example, North of Shanghai (released on January 24, 1939), is the first spy noir in which the Japanese are explicitly made the enemy. Here, the things the Chinese do aren’t “illicit”; what they do is heroic.

Hollywood’s uplifting depiction of the Chinese didn’t occur because war-time experiences led American WASP audiences to tolerate an “enlargement of whiteness” that extended beyond “hyphenated Americans” of European descent. That is, it didn’t occur because of a racial consideration – the only one that Flory is concerned with. Instead, the positive portrayal of the Chinese (and its opposite, the negative one of the Japanese) was based on political and military considerations: the Chinese were a US ally, whereas the Japanese were an enemy. Spy noirs and other spy films consistently show this dichotomy.

Flory is wrong to allege that “some positive characterizations” of Asians in film noir didn’t occur until the post-war years (“as the classic period progressed”). In the WWII era – in the immediate years before and after the release of The Shanghai Gesture – Hollywood made sure audiences saw the gruesome brutality the Chinese suffered from the Japanese as well as their unbreakable resistance.

In fact, the second US spy noir, International Settlement, was also, according to Daily Variety, “The first feature picture dealing with the bombing and military devastation of Shanghai ready for release…[and]…News clips are effectively inserted with the studio material.”33

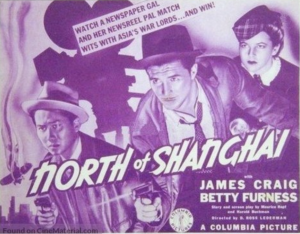

In North of Shanghai, a pistol-toting cameraman (James Craig) and a star reporter (Betty Furness) bust up a pro-Japanese spy ring and avenge the murder of his Chinese friend (Keye Luke), a fellow news photographer.

In North of Shanghai, a pistol-toting cameraman (James Craig) and a star reporter (Betty Furness) bust up a pro-Japanese spy ring and avenge the murder of his Chinese friend (Keye Luke), a fellow news photographer.

Dan Flory and James Naremore share the same two drawbacks in their respective treatments of “Asia” and “Asians.” First, they don’t understand that there is more than crime noir in the noir filmography – there is also spy noir. Second, they don’t recognize the historical context of Asia in World War II, which results in their unitary treatment of Asians.

According to Rana Mitter, the influence of Cold War and post-Cold War politics on American historiography about China explains the ignorance of Americans about the China-US relationship in WWII. Although that argument is beyond the scope of this post, Mitter presents it in the Epilogue of his book. What I want to emphasize is that Hollywood was unwaveringly pro-China during the WWII era in spy noirs (and other spy films).

To see Hollywood’s depiction, at that very time, of America’s “forgotten ally,” as well as to see a different representation of “Asians” in film noir than is given by James Naremore and Dan Flory, I recommend watching the spy noirs that I cite above.

Spy Noirs Refute Claims that Film Noir Is Derived from Hardboiled Crime Fiction

For decades, mass media journalists and academic historians have repeated the same two claims about the origins of film noir. First, its content derives from literature, foremost of which is hardboiled crime fiction. Second, its visual style derives from European émigré film professionals, who drew on their familiarity with expressionism once they were in Hollywood. Spy noirs contribute to exposing both claims as false, that each is only a myth.

The commentary below, in Andrew Spicer’s Historical Dictionary of Film Noir, under the subsection “THE ORIGINS OF FILM NOIR,” is representative of the first myth.

The commentary below, in Andrew Spicer’s Historical Dictionary of Film Noir, under the subsection “THE ORIGINS OF FILM NOIR,” is representative of the first myth.